Castelao: caricature as a useful art form

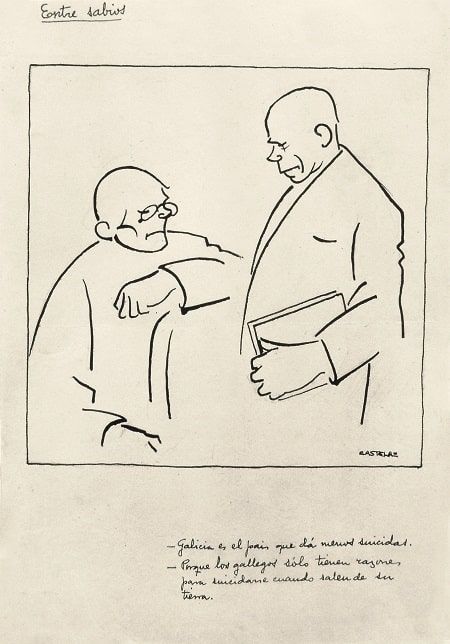

Castelao felt himself to be an artist before anything else and was a central figure in Galician culture for a long time, expressing his social and political concerns in caricatures that for him should reflect the truth and be an art capable of changing things for the better.

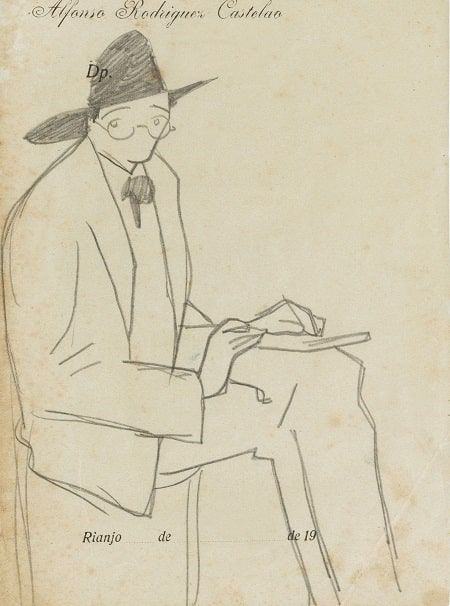

Doctor, caricaturist, writer, painter, scenographer, essayist, historian, Alfonso Daniel Manuel Rodríguez Castelao (Rianxo, A Coruña, 1886-Buenos Aires, 1950), was above all a self-taught artist who became one of the most important figures of 20th-century Galician culture and confessed that his true desire was to live from art, something that, despite his prolific and varied production, he would never fully achieve.

Although born in Galicia, Castelao lived his first years in the Argentine town of Bernasconi, in La Pampa, where his father had emigrated. He lived there until 1900 when the family decided to return to Galicia. Castelao enrolled in the General and Technical Institute, with a Bachelor of Arts, and between 1903 and 1909 he studied Medicine at the University of Santiago de Compostela.

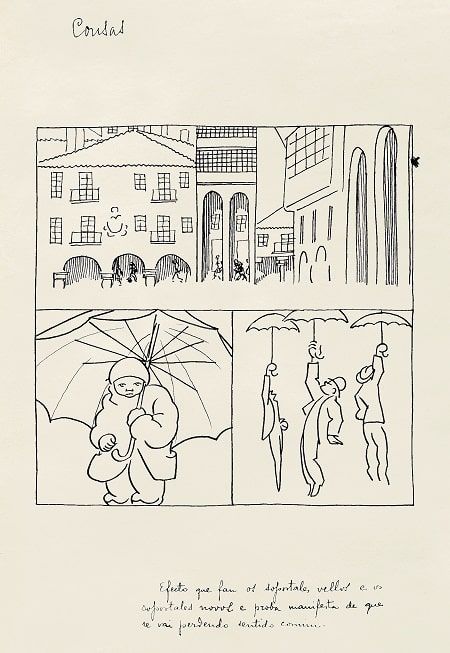

In 1908 he exhibited his first caricatures in Madrid, where he participated in the II and III Salón Nacional de Humoristas and began to collaborate as an illustrator with the magazines Vida Gallega and El Cuento Semanal. These were the years in which he elaborated his artistic language, exploring the possibilities of caricature, experimenting with painting in small and large formats, and capturing certain themes that reflected his concerns such as poverty, blindness, and emigration.

But Castelao can hardly be understood without taking into account the twenty years he lived with his family in Pontevedra. After suffering a detached retina, from which he partially recovered after an operation, he abandoned medicine and applied for the National Institute of Statistics, obtaining a position in the capital of Pontevedra, where he arrived at the beginning of 1916.

In those years, Pontevedra enjoyed a bustling social and cultural life, which Castelao joined immediately. His arrival in Pontevedra also coincided with the beginning of an active political commitment that intensified when he made contact with the Galician intellectuals of the city and his integration in the Karepas Rowing Club, which, imitating the English clubs, gathered young university students under the slogan "rowing and sandwiches".

Castelao also promoted the foundation of the Pontevedra branch of what was the first Irmandade da Fala, an organization for the defense and promotion of the Galician language. The Galician spirit impregnated since then all his artistic and literary production.

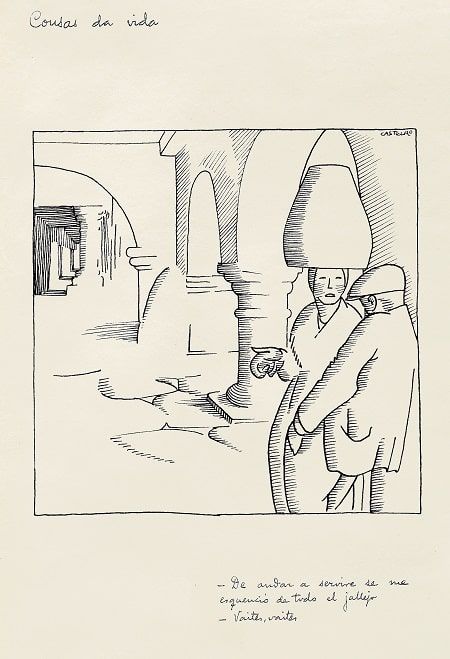

He began to publish assiduously in the bulletin A Nosa Terra, initiating his facet as a storyteller, which he would call "cousas". At this time some of the recurring characters of his work appear, such as the one-armed homeless man, whom he introduces as "O Probe Xan".

He also collaborated on the magazine Nós, founded in 1920 by Antón Losada Diéguez, Vicente Risco, Ramón Cabanillas, and Castelao himself, who besides proposing the name of the magazine assumed its artistic direction.

The new Galician art

Castelao believed it was necessary to establish the bases of new Galician art because as he expressed, "all Art has its homeland, all Art is the fruit of some land". This led him to promote conferences, meetings, and exhibitions to promote this new Galician art, which for him should not be inspired by external influences but should be based in Galicia. To this end, he had to look to popular art, which possessed the true Galician spirit.

One of the most characteristic and authentic manifestations of popular art he recognized in the stone crosses, being responsible for dignifying this type of work and the first to give them an academic consideration. Another of his contributions consisted in the creation of typography that, at first sight, could be identified with Galicia. On this occasion, his sources were the documentation of medieval epigraphy.

However, it was graphic art that captured his attention and became his main activity. In his university years, he had already shown his inclination towards drawing, painting, and, above all, caricature, a discipline that he learned during his childhood in Argentina with the magazine Caras y Caretas.

The art of caricature of Castelao

Castelao abandoned large-format works to focus on caricature, which for him, allowed him to reflect the character of the character, its essence. He was not interested in caricature as a mockery and exaggeration of the physical defects of the portrayed. In his opinion, the caricature had to be based on truth and had to be true, and the artist had to be aware that his art could be capable of changing things for the better.

As an artist, Castelao was self-taught. He had a great facility to synthesize features, capture scenes, to condense. One of his merits lies in his ability to capture the psychology of those he depicted through the quick and minimal strokes of his drawings, and in his capacity to transmit his message. The humanity reflected by the protagonists of his social and political cartoons gave them a universal and accessible character.

With the Civil War, Castelao went into exile, first in New York and later in Argentina, where he died in 1950 in the sanatorium of the Galician Center of Buenos Aires. During this period his work continued, including Debuxos de Negros, a series of drawings showing scenes of Afro-American music and culture made in Cuba and New York.

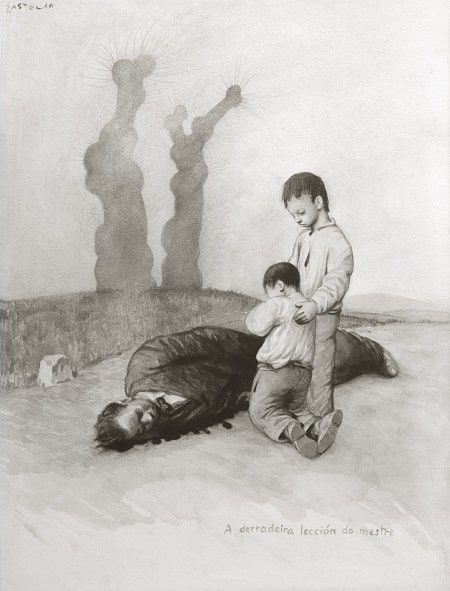

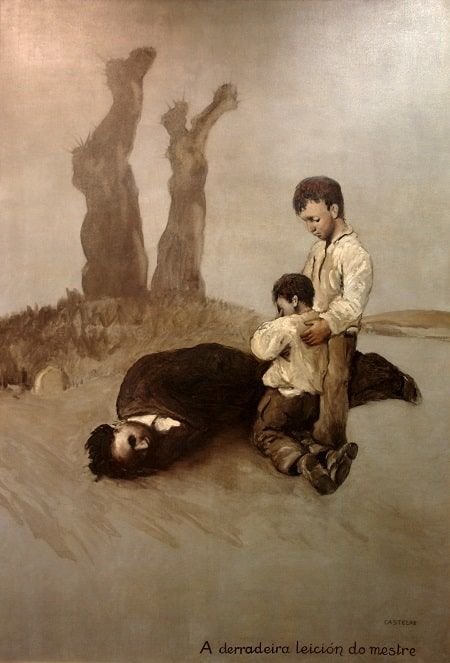

This oil painting, 2 meters high by 1.40 meters wide, was painted in 1945 based on the print number 6 of the book "Galicia Mártir", a work focused on the Civil War in Galicia and portrays a teacher murdered in front of two children who cry in shock before his corpse.

At that time, the artist wanted to make a kind of pictorial testament, so he decided to make a change in the plastic language, although he kept the essence and spirit of the print made in 1937.

Source: Inclusion