What is the aquatint printing method and why is it called that?

Learn more about the aquatint printing method, including what it is and why it is called by that name.

Tonal gradation has always been an issue for printmakers. And how could it not? While a painter fills a canvas with a mysterious shadow, an ominous storm cloud, or a mysteriously shadowed face with a single brushstroke, printmakers must achieve this mood with a line. But don't expect any appeasement from a graphic artist.

In copper engraving, rules for crossing lines, dotting, and putting a lot of them together were made as early as the Middle Ages so that volume, area filling, and luminous boundaries could be made. In the first half of the 17th century, Lieutenant-Colonel Ludwig von Siegen, an artist of the city of Kassel, gave engravers a hand by coming up with the mezzotint. The key to this technique is the way the metal cliché is grated by a machine. This gives the engraving line pattern areas that are perfectly dark and areas where the light changes in a sensual way.

It turns out that the first aquatint was also made at the same time. Yes, this will not be the first time an aquatint is made. The first person to make one kept it a secret, which is why another artist from a century later is often credited with making it. But first, let's go back to when the aquatint was first made.

Dutch Golden Age: From the Beginning of the Netherlands to a Citadel of World Trade, Art, and Civic Initiative

After the United Republic of the Seven Provinces was formed in 1588, the areas near the lower Rhine and Main rivers grew at a rate that had never happened before. In history, this time is called the Dutch Golden Age. At the time, only 1.5 million people were living in the seven provinces. However, the new republic controlled the world's maritime trade routes and built a navy that was bigger than those of England and France combined. Also, the religious divide caused a lot of Protestant craftsmen to leave the Spanish Netherlands and move to the new republic.

In a short amount of time, Amsterdam went from being a small port city to be a center of international trade, art, and civic action.

These historical events also had a direct effect on how art was made and how the art market worked. Holland was starting from scratch to create a new identity that was based on free trade, diversity of thought, private initiative, and Protestant individualism. The church's important role in art and society as a whole was cut down to a minimum.

In 1640, an English traveler noticed that almost every house of a Dutch blacksmith or shoemaker had paintings on the walls. The art market was full to the brim. No longer the church or the monarch, but the bourgeoisie as a whole commissioned works of art. Still-life paintings, floral compositions, gastronomic compositions, peasant life, landscapes with animals, watching craftsmen at work, interiors, cityscapes, and seascapes were all types of art that didn't exist before.

Except for the group portraits of towns, the paintings were small because that was what the new market wanted. In Holland, there were always art fairs, but most artists only painted one type of art or subject. The great religious themes, canons, and debates fell out of the mainstream of art. They were replaced by the triumph of the masses and making art more accessible to the masses.

Under these circumstances, using stamps to make art was a very profitable venture, so it's not surprising that prints were also popular in Holland. Ludwig von Siegen moved to Amsterdam in 1643. At the time, he was a lieutenant governor at the court of Hesse-Kassel. He gave Europe the important technique of mezzotint, which is a toned engraving. And it didn't take long for etching to be used to make something similar.

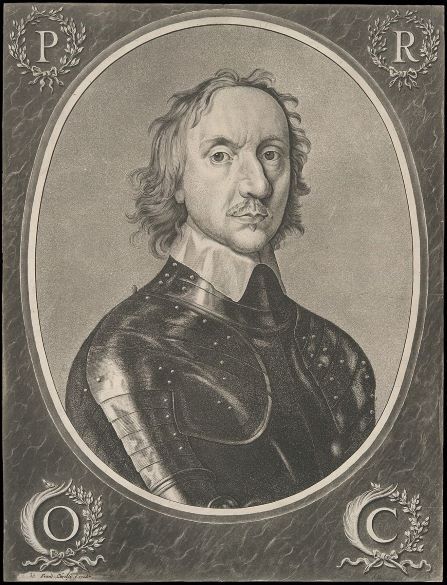

Jan van de Velde IV, a painter and printmaker who lived from 1610 to 1686 and was born in Utrecht and died in Haarlem, was one of those who liked trying new things and went with the times. In his work, he used a new technique called mezzotint, but no one knows how he got to the point where he etched powdered grain.

The Dutch master lived at the Swedish royal court from 1651 to 1654, where he painted a portrait of Queen Christine. Even though van de Velde never talked about how he did his work, it is clear to anyone who looks at this portrait that the figure is an aquatint. A few years later, in Amsterdam, van de Velde used this method, which was new at the time, to make more portraits.

What is the aquatint and who invented it?

The aquatint technology is based on the same principles introduced in 1500 by the Swabian artist Daniel Hopfer from Augsburg, combining copper engraving and decorative etching of iron armor. This technique uses a polished copper plate coated with an acid-resistant varnish. The design is scratched into this layer of varnish and etched in a solution of copper sulfate or nitric acid. This produces a line, while tinting of the area can be achieved with aquatint.

The copper plate is coated with rosin powder and the powder is melted to the surface of the plate by heating the plate from below with a torch. Each particle of the molten rosin powder forms an acid-resistant sphere on the surface of the plate, while the depressions between these spheres are open to etching. This produces a negative relief which, when printed on paper, produces a continuous color tone.

Since Jan van de Velde kept his trade secret and no one ever found out what he was doing in his studio, it took another century for the family of printmakers to reach their desired objective.

Around 1770, the well-known British watercolorist and mapmaker Paul Sandby gave the process of etching powdered grain the name aquatint. Since one of the goals of aquatint was to mimic the feel of watercolor, it makes sense that a member of the watercolor community would be interested in it.

Jean-Baptiste Le Prince Intaglio Printmaking: A Novel Technique

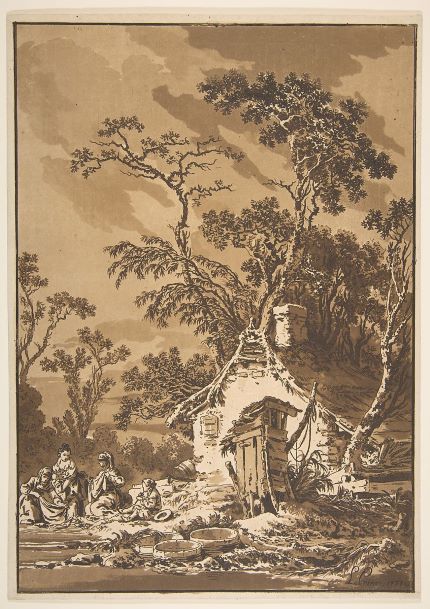

In the mid-1980s, several printmakers rushed to find the "holy grail" of intaglio printing. This process was eventually crowned by the efforts of Jean-Baptiste Le Prince (1734, Metz - 1781, Lanier-sur-Marne), a pupil of the French graphic artist and painter, the brilliant Lacquartier Francois Boucher. He showed his aquatint works to the public in 1768 and they were greeted with genuine enthusiasm in certain circles.

But, like van de Velde, Le Prince wasn't in a hurry to tell the public about the technical parts of his invention. The well-known French literary magazine Mercure de France was very interested in the topic and hoped that Jean-Baptiste Le Prince would share his technique with the public. This would make it possible to publish works by artists that were kept in private collections or even all of the works from the annual Paris Salon.

Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, on the other hand, did not want to make a philanthropic gesture and stubbornly continued to keep the technique a secret. However, where there's grain, there are mice, and the secrets of the aquatint trade were gradually leaked. Faced with this harsh reality, Le Prince approached the French Academy of Sciences with an offer to buy the aquatint technology from him. No such deal materialized and in 1780, Le Prince went one step further and published a catalog of 30 to 40 copies of the aquatint with a description of the aquatint technology.

Unfortunately, Jean-Baptiste Le Prince did not get the financial return he deserved, because a year later he went to serve the muses in the printing workshops of the world beyond. In the meantime, his brainchild enjoyed a brief but vivid burst of fame. The great Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya produced a series of canonical prints in the aquatint technique - 'Caprices' (1799), 'Horrors of War' (1810-1819), 'Bullfights' (1816) and 'Follies' (1816-1823).

The Triumph of the Aquatint in the Second Half of the 19th Century

The aquatint didn't stay on top for long. At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, when Munich playwright Alois Seinfelder discovered lithography, many intaglio printing techniques, especially tonal ones, lost their appeal to book and newspaper publishers as well as artists. But the aquatint had a renaissance in the second half of the 19th century when it was used as an art form again.

This was largely stimulated by the World Exhibition in Paris in 1867, at which a large exhibition of crafts, applied and statuary arts was organized by Japan, which had just ended its isolationist policy. The glow of this Eastern civilization, shrouded in mystery, had an impact not only on the masses but especially on Impressionist artists.

The ancient ukiyo-e polychrome woodcut technique was admired, copied, and interpreted. The French-American artist Mary Cassatt adopted the stylistic techniques of Japanese art and the pastel palette but chose European printmaking methods of etching and aquatint for her prints. Several other Impressionists also began to use the aquatint process in their work, among them such names as Edouard Manet, Félicien Ropp, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Jacques Villon.