How the crisis in Venezuela affects criminals?

Some criminals in Venezuela have left the world of crime and sought more honest work abroad, fearing harsh punishment in other countries.

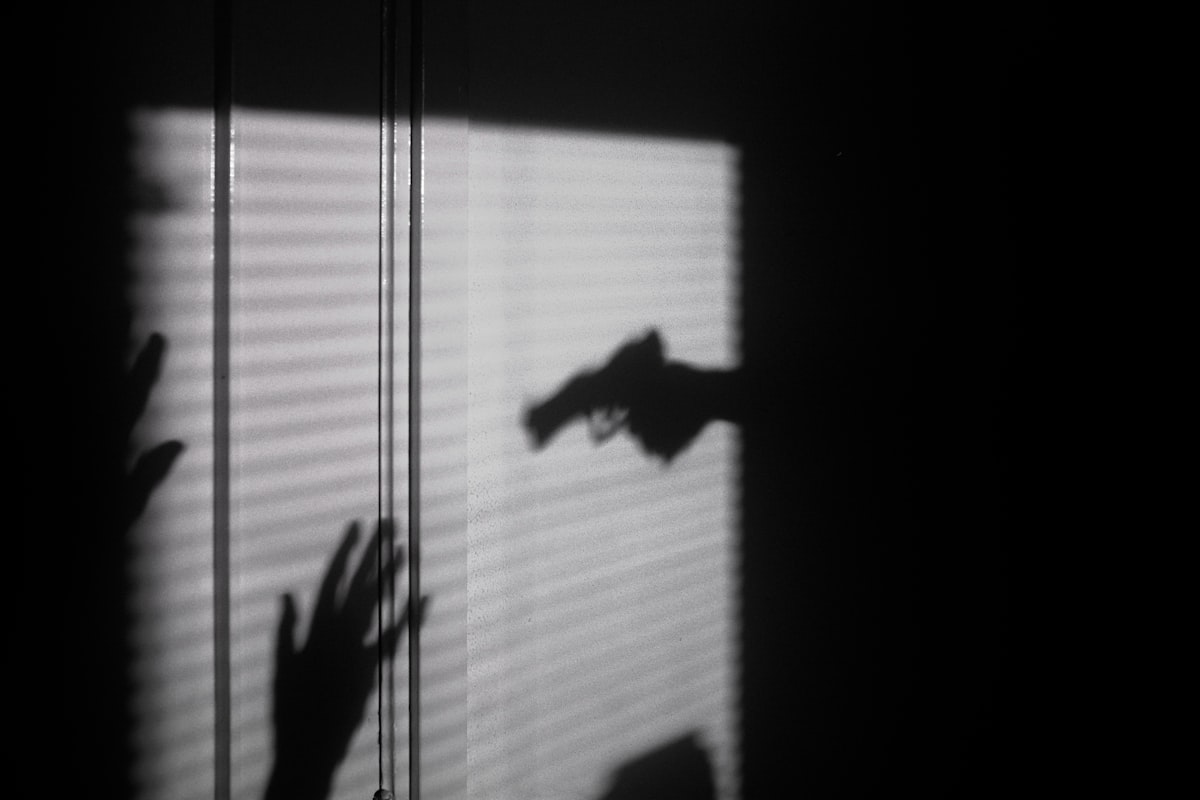

Some criminals in Venezuela have left the world of crime and sought more honest work abroad, fearing harsh punishment in other countries. The feared gang member El Negrito sleeps with a gun under his pillow and says he has lost count of the people he killed. But despite its fiery appearance, it soon complains about how the economic crisis in Venezuela has affected its income.

Firing a firearm has become a luxury. Bullets are expensive, a dollar each. And now that less cash circulates on the street, thefts are no longer as profitable as before. For the gang member of 24 years, that has been something simple: even for criminals, it has become more difficult to make ends meet.

"If you shoot a comb (charger), you're shooting $ 15," said El Negrito, who spoke with The Associated Press on condition of being identified only by his nickname and photographed with a hood and face covered to avoid unwanted attention. "If you boot a gun, or the cops take it from you, you're throwing $ 800."

The president's socialist government, Nicolás Maduro, stopped publishing crime statistics for some time.

But in a kind of unexpected advantage of the suffocating economic crisis, experts point out that assassinations and armed robberies have plummeted in one of the most violent countries in the country. In the Venezuelan Observatory of Violence, a non-profit group based in Caracas, experts estimate that homicides have fallen by up to 20% in the last three years, based on data such as media reports and sources in local morgues.

The decline is directly related to the economic collapse that has helped fuel the political dispute over control of the once-rich oil nation.

Economic crisis hits criminals pockets

Inflated inflation reached a million percent last year, making the local bolivar almost useless even though ATMs could not give more than the equivalent of a dollar. The severe shortage of food and medicines has led some 3.7 million people to seek better prospects in places like Colombia, Panama, and Peru, mostly young men, the kind of person they try to recruit gangs. And the days of work are often interrupted by national strikes.

But as the country moves towards anarchy, many Venezuelans who resort to crime are subject to the same chaos that has led to a social and political collapse.

The critical voices blame the 20 years of socialist revolution initiated by the late President Hugo Chávez, who expropriated once-prosperous businesses that today produce a fraction of their potential under the management of the government.

Opposition leader Juan Guaidó, president of the National Assembly and recognized as president in charge of more than 50 countries, began this year a campaign with US support to overthrow Maduro, which succeeded Chávez. However, it has not yet managed to fulfill its promises to restore democracy, reactivate the economy, and make the streets safer.

Due to the chaos, crime has changed rather than disappear. Although armed robberies have been reduced, reports of robberies and thefts of anything from copper telephone wires to cattle have risen. Drug trafficking and illegal gold mining have become the default activities of organized crime.

Streets of Caracas

When night falls, the majority of Caracas residents leave the streets in an unofficial curfew fearing for their safety. Despite the significant decrease in violent deaths, Venezuelans tend not to look at their cell phones in the street. Many leave gold and silver wedding bands in safe places at home, while others have become accustomed to checking if they are being followed.

"Venezuela continues to be one of the most violent countries in the world," said Dorothy Kronick, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania who has conducted extensive research in Caracas' barriadas. "It has levels of violence like a war, but without war."

El Negrito leads a group of mercenaries called the Crazy Boys, a gang that is part of an intricate criminal network in Petare, one of the largest and most feared slums in Latin America. The leader, who accepted an interview with two companions in his hiding place in Caracas, said that his group now commits five kidnappings a year, much less than in previous years.

These fast kidnappings are big business. Normally, the victim is captured and held for up to 48 hours while their loved ones try to collect as much cash as they can. The captors focus on the speed and quick return of the victim, rather than the size of the payment.

The rescue they fix depends on the cost of the victim's car, said El Negrito, and the operation can end in death if their terms are not met. But like many of his peers, he has considered leaving the business in Venezuela and emigrating.

Some people have left the world of crime and sought more honest work abroad, fearing harsh punishment in other countries where there is more compliance with the law.

While explaining that it is difficult for him to support his wife and small daughter, El Negrito passed from one hand to another a silver pistol. The breeze moved the pages of a Bible that rested on a chest of drawers, opened by the Proverbs.

Less money equals less to steal

Robert Briceño, director of the Venezuelan Observatory of Violence, said that the decline of homicides is a matter of basic economy: faced with the shortage of cash in Venezuela, there is less to steal.

"Of those who produce wealth, now none is well: neither the honest citizen nor there are opportunities for the offender."

A member of the Crazy Dogs who only identified himself by his nickname, Dog, said he finds it difficult to find ammunition for his weapons on the black market. The challenge is to pay them in a country where the average person earns $ 6.50 a month.

"This gun used to cost a ticket for these," he said, crumpling a 10-bolivar bill that would no longer be enough to buy a cigarette. "Now this is nothing."