David Alfaro Siqueiros Murals at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso

At the Old San Ildefonso College, you may learn about the murals painted by David Alfaro Siqueiros.

During his stay in Barcelona, Spain, where he held the position of the first chancellor of the Mexican Consulate, Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros published in May 1921, in the only issue of the magazine Vida Americana -of which he was editor-in-chief and artistic director-, the manifesto Three appeals of current orientation to the painters and sculptors of the new American generation, in which, among other things, he wrote: "Let us painters superimpose the constructive spirit over the solely decorative spirit; color and line are second-order expressive elements; what is fundamental, the basis of the work of art, is the magnificent geometrical structure of the form with the conception, meshing and architectural materialization of the volumes and the perspective of the same, which by making 'terms' create the depth of the 'environment' [...]"

A little more than a year later, Siqueiros returned to Mexico and joined the group of plastic artists that José Vasconcelos, then Secretary of Public Education in the government of President Álvaro Obregón, had called together to paint the walls of the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, then converted into the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (National Preparatory School).

Diego Rivera was already working on his first mural, La creación, in the school's amphitheater, and José Clemente Orozco, Fermín Revueltas, Jean Charlot, and Ramón Alva de la Canal already had their own spaces where they could give free rein to their talent and creativity.

"Siqueiros, who at the time was 26 years old, was assigned the walls surrounding the staircase of the so-called Colegio or Patio Chico del Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso because they were the only ones available," says Dafne Cruz Porchini, a researcher at the Institute of Aesthetic Research dedicated to the study of modern art in Mexico.

A vaulted and dark place

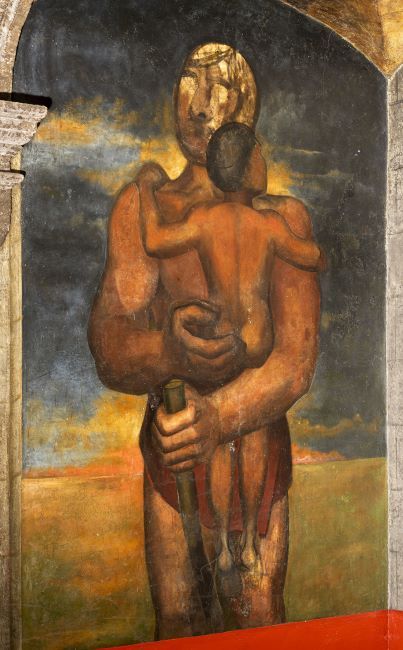

Siqueiros painted in the stairwell, a vaulted and dark place, The Elements and The Myths; and in the upper part, whose walls are higher, The Burial of the Sacrificial Worker and The Call to Freedom.

All these works, created between 1923 and 1924, were his first murals and, according to the university professor, already announced in some way what Siqueiros would later paint in other public spaces such as the Palace of Fine Arts.

"While the subject matter of the first two, in encaustic, is rather allegorical, that of the other two, in fresco, is political and coincides with the publication of the first issue of El Machete, the official organ of the Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors Union (SOTPE), in whose foundation Siqueiros himself participated," she adds.

Technical problems

When he began painting these murals, Siqueiros was overwhelmed by various technical problems. He was facing an architecture that was certainly complex, and it cannot be forgotten that muralism also implied adapting to a pre-existing architectural space.

But thanks to the communication established between him and the other painters working at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, who had never faced a wall before, he was finally able to solve them. In addition, he collaborated with Xavier Guerrero and Roberto Reyes, two plastic artists who had already experimented with mural painting.

As for The Elements, Siqueiros intended to present a new proposal that did not look like anything else. However, Jean Charlot evoked in it the spirit of the West falling on the New World and Diego Rivera understood it as an angel of "Syrian-Lebanese Michelangelo" (in allusion to the supposed origin of the painter from Chihuahua).

As for the Entierro del obrero sacrificado, Siqueiros began it -but did not finish it- as a tribute to Felipe Carrillo Puerto, politician, journalist, revolutionary leader, and governor of Yucatán who had just been assassinated (January 3, 1924).

"In this mural, which highlights the use of volumes and colors, and the handling of the human body with evident indigenous features, as well as in El llamado a la libertad, also unfinished, the hammer and sickle appear as symbols of the left and popular demands. It can be said that these two works are the synthesis of what Siqueiros was living and thinking at the time," says Cruz Porchini.

Clashes with bullets

As was to be expected, Siqueiros and José Vasconcelos drifted apart, since the latter was convinced that art and culture were, per se, tools that helped to achieve social change, but that they should not be contaminated with political issues (later, on July 27, 1924, he would resign from his post as Secretary of Public Education).

As if that were not enough, the students of the National Preparatory School, "under the influence of many of their old reactionary teachers, both in politics and in art," began to attack Siqueiros and his colleagues for what they were painting on the walls of the school.

In his memoir Me llamaban el Coronelazo, Siqueiros refers, "So serious was the situation, that we painters had to defend ourselves with bullets from the shots frequently fired by the students, undoubtedly more against our works than against ourselves, since their aim need not have been so bad."

"There is no doubt that this fact influenced the painter from Chihuahua to stop painting at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso," says the researcher.

In those days, José Guadalupe Zuno, who was governor of Jalisco, had contacted him and Amado de la Cueva to invite them to paint a mural at the Ibero-American Library of the University of Guadalajara. "Of course, this invitation also played a defining role in Siqueiros abandoning his work at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso. In the mural at the Ibero-American Library of the University of Guadalajara, titled Agrarian and Labor Ideals of the Revolution of 1910, we can appreciate a greater mastery of technique, but also of the themes, which allowed him to continue with his political militancy," concludes Cruz Porchini.