Dení Prieto Stock and the Mexican Left

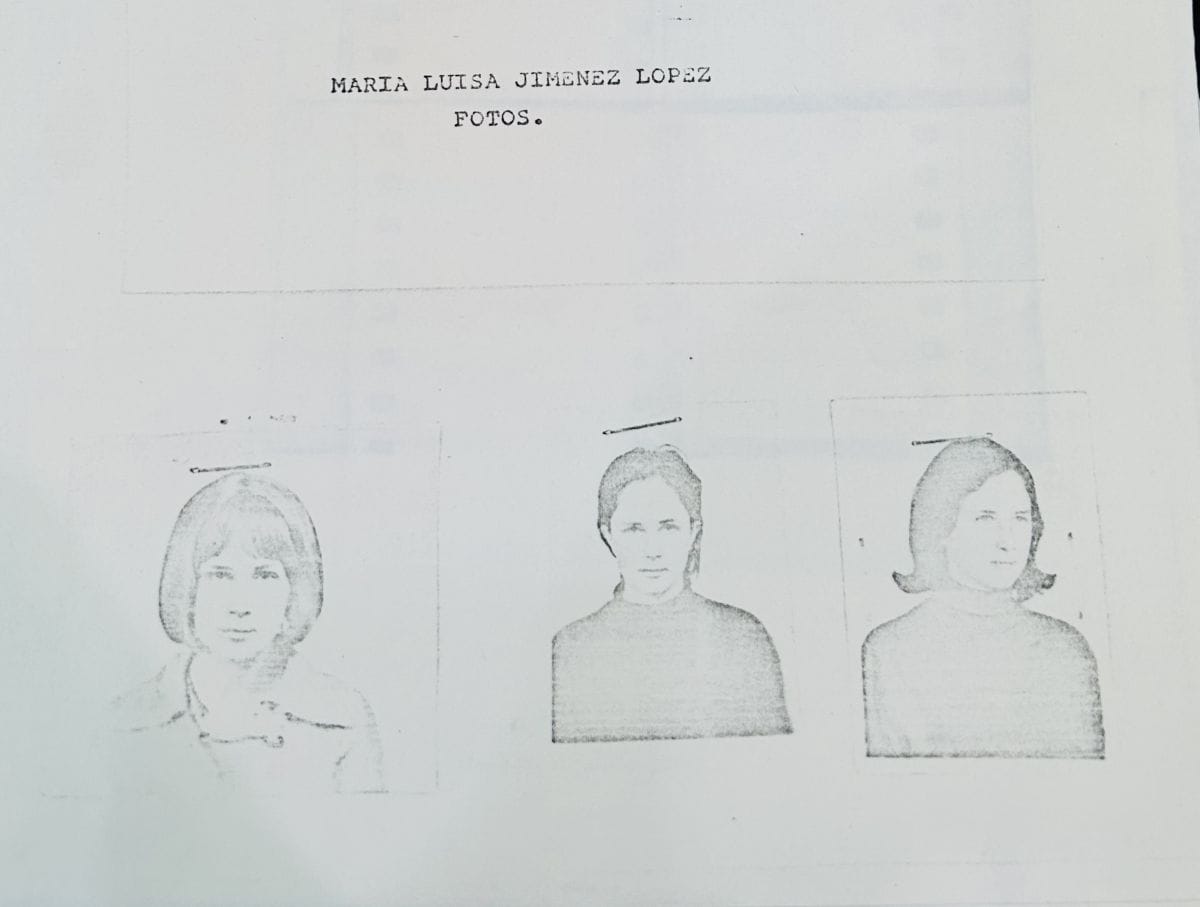

Dení Prieto Stock, a young revolutionary, joined the National Liberation Forces (FLN) in Mexico. Raised in a privileged family, she chose to fight for social justice. Her life was tragically cut short at 18, when she was killed in a shootout with government forces.

It’s the 1960s and 70s in Mexico, and if you wanted to live in peace and harmony while having an opinion, then good luck to you. Because those were the days when the government didn’t simply respond with a stern letter or a polite request to pipe down. No, they had other methods: methods involving soldiers, squads, and an unspoken agreement that human rights were merely an inconvenience. And among the throngs of brave souls who had the audacity to stand up against this was a young woman named Dení Prieto Stock.

Dení wasn’t just anyone. She was a spirited, firebrand intellectual, the kind you imagine rolling their eyes at the kind of pop drivel that makes the masses swoon. Her family background would make any dinner table conversation a thriller; she was brought up in a free-thinking household but had a grandfather who, to her horror, was one of Mexico’s staunchest anti-communists. You can imagine the dinnertime tête-à-têtes: Dení passionately defending the oppressed masses, while her grandfather gave her a steely glare, mumbling about how communism would ruin her.