A true story of a Diego Rivera-style scandal

A true story on how Diego Rivera, a pioneer in the ridiculing of public figures of the time, disregarded the warning of Mario Pani and painted a union leader in his mural.

A true story on how Diego Rivera, a pioneer in the ridiculing of public figures of the time, disregarded the warning of Mario Pani and painted a union leader in his mural.

In 1968, the Mexican army besieged Ciudad Universitaria, arresting 1,500+ students, teachers, and staff. 10,000 troops targeted the National Strike Council (CNH). The operation, involving the Olimpia Battalion and DFS (political police), led to imprisonment and disappearances.

Mexico City launches a pilot hydrothermal carbonization plant to convert organic waste into valuable resources. The first module processes 72 tons of waste daily, producing hydrochar (a coal alternative) and fertilizer, reducing CO2 emissions by 24,600 tons/year.

Starting in 2025, the TAOS II project in Mexico will hunt for trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) using stellar occultation. Three robotic telescopes will monitor 10,000 stars simultaneously, detecting the brief dimming caused by TNOs passing in front.

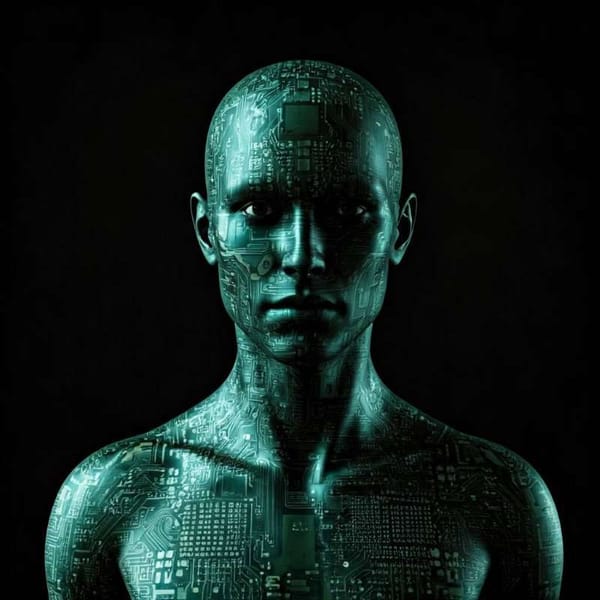

UNAM's FES Acatlán is developing a simulator to analyze the impact of technological disruption. Using case studies like cyborg Neil Harbisson, the project explores how tech challenges policy, security, and societal structures.