Dolores Olmedo, a Businesswoman, and Cultural Agent

Dolores Olmedo was convinced of the importance of opening spaces for culture; she rescued and repatriated the works of Mexican artists.

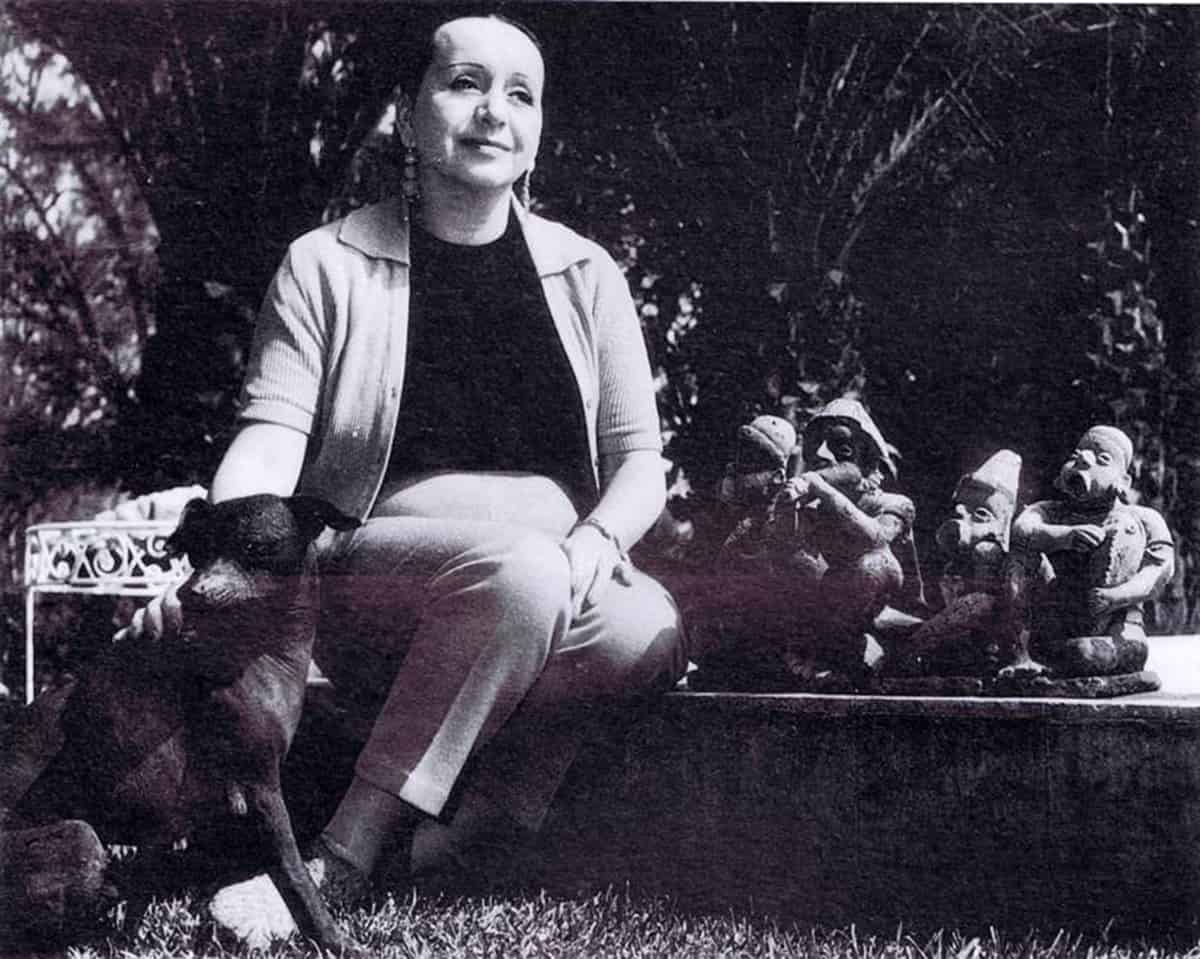

Two decades after her death on July 27, 2002, Dolores Olmedo should be remembered as a successful and hard-working woman, controversial and intelligent, who knew how to focus on business and connect with people who supported her career as a businesswoman and cultural agent.

Fortunately for Mexicans, she was interested in making money, in art and culture, so she invested part of her earnings in building an important collection of national art and in buying an exhacienda, home of the museum that bears her name. She was a collector who fulfilled her objectives and "that has benefited culture in this country," says university academic Ana Garduño Ortega.

The professor of the postgraduate course in Art History at UNAM refers that María de los Dolores Olmedo y Patiño Suárez (Mexico City,1908-2002), was a nationalist woman who firmly believed in the creation of institutions so that her name would be perpetuated; "we would not know her if she had not decided to found an important museum of modern art and galleries dedicated to her collection of popular art, or if she had not decided to collect Mesoamerican art. This desire for transcendence was very favorable for national culture".

On the occasion of her death anniversary, Garduño Ortega adds that she was an important ally of the power group that decided on hegemonic cultural policies and that she believed in the ideology radiated by the bureaucratic elite. She was not only convinced of the importance of opening spaces for culture but also of maintaining traditions and some customs that were being lost in the second half of the 20th century, such as the altars of Dolores (on Fridays during Holy Week) and the altars of the dead.

Olmedo knew how to establish strategic alliances that benefited her in economic and financial terms, and that allowed her to open a site as important as the "Hacienda de la Noria", in Xochimilco, south of Mexico City. "With her brickwork, she was related to very important construction companies, and she had the contacts to be assigned public works, she knew how to make alliances and businesses". And the most important thing: unlike other collections that are lost over the decades, this one did become an art museum.

The businesswoman was linked to the political class that governed Mexico during practically the entire 20th century; from the high spheres of power, she linked her business with her interests. "For the elite, it was important to have contact with intellectuals, artists, plastic artists, painters, and muralists," says the expert.

Dolores Olmedo and Diego Rivera: Art Movement in Mexico

Dolores Olmedo -interested in popular art, of which she forged "one of the richest and most interesting collections we have in Mexico"- maintained close contact with Diego Rivera, and with his influence, she began to collect pre-Hispanic pieces. At a time when it was legal to trade this type of heritage but illegal to take it out of the country, the famous painter bought pieces, original or fake, because he was not interested in the issue of authenticity.

Some were expensive because they were large or because of their state of conservation, which he could not acquire; he sent them to Dolores so that she could buy them. But he also gave her a list of works that he wanted to be rescued, if possible.

In this regard, the doctor in art history explains that the hegemonic artistic current that developed from the 1920s, the first international art movement in Mexico, was successful. It was avant-garde, proactive, with an evident nationalism, with Mexican themes and a strong emphasis on indigenous.

The works of national creators were sought after by residents of other countries or tourists who wanted to buy Mexican art. "There was a fashion for Mexico in the interwar period; when the American elite could not travel to Europe, which was in armed conflict or devastated, they visited our country a lot and bought art, with or without knowledge. Many of them didn't know what they were taking with them."

The national art of the first half of the century was practically marketed to the neighboring country to the north; numerous pieces nourished museums, through donations from the original buyers; in other cases, family members sold the pieces, in a second stage, to Mexican collectors; "that's where Dolores Olmedo came in, to repatriate pieces that went on sale in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s".

A Life-long Interest in the Mexican Art of Diego Rivera and Dolores Olmedo

Throughout her life, the businesswoman dedicated herself to "palming" the list that Rivera had given her. She attended galleries and auctions in the United States, and under the advice of the expert Fernando Gamboa, she acquired and brought to Mexico works of art that by then were already very expensive due to the prestige of the Mexican art movement, "with the idea of building a museum, because it was part of the moral commitment she had established with Diego". In addition to the easel paintings, Rivera's drawings, engravings, and even sketches of murals were added.

In addition, Dolores Olmedo broadened her interest beyond the muralist's work to include his women. She then incorporated Rivera's wives Angelina Beloff and Frida Kahlo into the collection. "Drawing concentric circles around him is the work of the two painters," Garduño adds.

No matter how controversial Olmedo's figure may have been at the time, the most important thing is that he rescued and repatriated the work of Mexican artists abroad, especially Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, and opened a museum to house them, for the enjoyment of those interested in visiting that venue.

It is relevant because there are collections created in the 20th century, with an important collection of modern, popular, European art, etc., which, however, are dispersed upon the death of the collector; many rich people do not get to create their museum or do not get to link their name with art in a permanent way, as it happened with Dolores Olmedo.

Today, her Museum (which will have an extension in the Aztlan Urban Park, in Chapultepec Forest) houses the largest collection of works by Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Angelina Beloff, and Pablo O'Higgins, as well as pieces of pre-Hispanic, popular, and even Novo-Hispanic art. "Following the example of my mother, Professor María Patiño Suárez, widow of Olmedo, who always told me 'everything you have, share it with your fellow men, I leave this house with all my art collections, the product of my life's work, for the enjoyment of the people of Mexico."