How Karl Marx Became the Rockstar of Political Theory

Karl Marx, born in 1818, navigated 19th-century Europe's tumultuous era, producing seminal works like the “Manifesto of the Communist Party”. Amidst rapid urbanization and political upheaval, Marx's insights into societal structures and capitalism's dynamics remain crucial readings today.

Karl Marx, born in 1818, emerged as a beacon in a Europe rapidly undergoing transformative change. Amidst this tumultuous backdrop, Marx's works and philosophy would come to define the core tenets of socialist and communist ideologies.

Karl Marx was born into a Jewish family, which, due to the prevailing anti-Semitic environment in 19th century Prussia, felt the need to convert to Christianity. This atmosphere, fraught with religious and political tension, was but a sign of the times. His early life was characterized by an impressive academic journey, obtaining a doctorate in philosophy by the age of 22.

This journey was punctuated by his writings on various subjects, notable among them being the “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right”, “The Jewish Question”, and “Theses on Feuerbach”. While the latter remained unpublished during his lifetime, its significance cannot be understated. It was during these formative years that Marx resided in Paris, soaking in its vibrant intellectual culture.

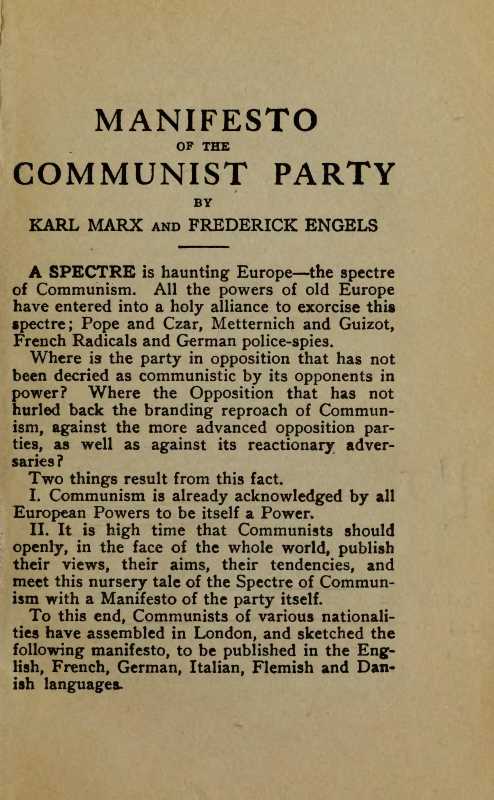

In 1847, Marx's path converged with that of Friedrich Engels. This meeting of minds would blossom into a lifelong friendship, leading to collaborative works that have left an indelible mark on world history. Their most prominent work, the “Manifesto of the Communist Party”, published in 1848, was not just a publication; it became a clarion call. It resonated across the world, embodying the aspirations and struggles of the working class. However, such revolutionary thoughts were not without consequences. Marx soon found himself facing political persecution, forcing him to flee to London.

London was more than just a refuge for Marx. It was here that he delved deep into the intricacies of capitalist economies, culminating in the publication of “Capital”. The work, spread over three volumes (with the latter two being posthumously edited and published by Engels), is a cornerstone in the realm of social sciences. Dissecting the capitalist machine, it, remains a subject of intense debate and discussion even today.

Marx was not just a philosopher in an ivory tower; he was deeply committed to the pressing needs of his time. The 19th century saw Europe on the cusp of an industrial revolution. Technological advancements and new organizational methods skyrocketed productivity. The landscape bore witness to this upheaval, with mines, factories, canals, and roads dotting the horizon. These infrastructural marvels, however, came at a cost. Peasants, searching for a livelihood, migrated to burgeoning cities, often working inhumane hours for meager pay.

The winds of change also brought with them ideals of socialism, liberalism, and nationalism. This period was marked by a series of revolutions across Europe and Latin America in 1848. Furthermore, the Paris Commune of 1871 stands out as a testament to workers' aspirations. This exercise in direct democracy, though short-lived, ended tragically with the death of approximately 30,000 communards.

Marx passed away on March 14, 1883. But his legacy, intertwined with the fabric of 19th-century Europe, continues to influence global political and economic discourse. In a world of rapid change and disparity, understanding Marx is more than just an academic exercise; it's a journey into the soul of modern society.

Hegel's Influence on Young Marx

In his early years, Karl Marx found himself greatly inspired by the work of Friedrich Hegel. Surrounded by the young leftist Hegelians, Marx nurtured a close intellectual bond with this group. This relationship was instrumental in shaping his preliminary writings. The Hegelian dialectical method, a process of change in which a concept or its realization passes over into and is preserved and fulfilled by its opposite, deeply impacted Marx's approach to socio-economic analysis.

From Idea to Material Conditions

As Marx matured, he revisited Hegel's methods, but instead of keeping them in the abstract realm of ideas, he grounded them in the tangible world of capitalist production. This transition is perfectly encapsulated in the passage that explains how Marx reinterpreted Hegelian thought:

"Marx removed from Hegel's theory the assumption that nations are the effective units of social history. He substituted the national struggle with the struggle of social classes. This was a paradigm shift - from the nationalism, conservatism, and counter-revolutionary tenets of Hegelianism to a revolutionary radicalism. As a result, Marxism became the cornerstone of 19th-century party socialism and, with further modifications, paved the way for modern communism." - (Sabine, 1976, p. 545)

While Marx's reinterpretation distanced him from some of Hegel's key doctrines, it breathed new life into the philosophy, making it relevant to the pressing socio-economic issues of his time.

Marx's Continuation of Hegelian Thought

While Marx forged his path, it would be remiss to overlook how he carried forward some of Hegelian philosophy. According to George Sabine, a prominent historian of political theory, there are two main aspects where Marx's philosophy mirrors Hegel's:

- Dialectical Approach: Both philosophers believed in the power of the dialectical method. For Marx, just as for Hegel, dialectics wasn’t just a logical method; it was the only tool capable of unveiling the laws of social development. In this light, Marx's philosophy, like Hegel's, can be seen as a philosophy of history.

- The Power and Struggle Dynamic: Both thinkers held that the essence of social change is the struggle. Whether it's the clash of ideas for Hegel or the clash of classes for Marx, the ultimate determining factor in both their theories is power. This belief is the bedrock on which societies evolve and reshape.

Karl Marx and His Reflections on Democracy

Karl Marx is widely recognized for his intense focus on economic issues. His vast intellectual contributions primarily revolve around economic matters, rather than explicit discussions on the challenges of democracy. However, by delving into some of his texts, notably the Manifesto of the Communist Party, one can discern inklings of an original contemplation on the democratic process.

Marx's Threefold Vision on Democracy:

- Universal Suffrage and Annual Elections: Marx advocated for the imperative of universal suffrage. He believed that the real voice of the people could only be heard if there were elections every year. This frequency would also counteract any tendency of representatives to deviate towards serving their personal interests, rather than the collective good of the masses they represent.

- A Critique of the Executive Power: Marx placed significant emphasis on limiting the power of the executive branch of government. He was of the firm view that a robust legislature was vital for a true democratic state. He contended that out of the three branches of the state – the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary – it was the legislature that most embodied the spirit of democracy. Thus, socialist democrats should rally behind the legislative branch and shield it from potential encroachments by the executive or the judiciary.

- Reformation of the Bureaucracy: Marx sought a drastic change in the very makeup of the state's bureaucracy. He envisioned a state apparatus where the working class sat at the crux of public administration. He aimed to tear down the traditional, often alienating, bureaucratic barriers and proposed to democratize it via competitive elections. His ambition was to transform the state from being an aloof entity overseeing its people, to an institution genuinely directed and controlled by its citizens.

While Marx didn’t explicitly outline the mechanics of how such a bureaucratic transformation would occur, he drew inspiration from the Athenian model. This model was emblematic of direct democracy, where citizens rotated roles between being the governors and the governed, facilitated by lotteries. Such a system fostered enhanced equality and ensured comprehensive participation in representation.

An underlying theme in Marx's reflections on democracy is the intrinsic link between economic and political spheres. Marx firmly believed that a radical overhaul of the economic realm would naturally precipitate an equally profound transformation in the political domain.

Contradiction of Capitalism vs. Democracy

Marx recognized a profound discrepancy between the tenets of democracy and the practices of capitalism. On one hand, democracy celebrates political rights and civil liberties, fostering a sense of inclusivity and participation. However, in stark contrast, capitalism often propagates growing inequalities, widening the chasm between different social classes.

In Marx's perspective, this incongruence is not just a minor disparity but a foundational flaw. It underscored his belief in the necessity of transcending the capitalist mode of production to realize a truly classless society, a notion he fervently advocated for in 1848.

Representative Democracy and Its Potential

Yet, Marx was not entirely dismissive of the existing structures. He believed that by radically intensifying representative democracy — extending it to the very bounds of universal suffrage and reshaping the state to better represent working-class interests — it could serve as a formidable force to challenge this inherent contradiction.

His belief in the potential of democracy was further galvanized by the emergence and subsequent suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871. The Commune marked a significant chapter in the history of class struggle, birthing a brief instance of a workers' republic, characterized by direct democracy, egalitarian decision-making processes, and fair wage structures. This episode was a testament to Marx that the working class had the capability to wield political power.

Therefore, he believed that the swift and violent demise of the Commune was at the hands of conservative European forces. This demise affirmed Marx's belief in the need for workers to dismantle the existing state structure and erect one that truly represented their interests.

Marx's Vision for Democracy on the Path to Socialism

Drawing on these insights, Sanchez (1983) surmised Marx’s view on democracy's role in transitioning to socialism. For Marx, democracy was not just a vehicle, but also an outcome of the process of moving towards socialism. The real expansion and enrichment of democracy, in essence, signifies society reclaiming powers that had been monopolized by the state. According to the Marxian analysis, in this new societal construct, leveraging the state for the working class's advantage is insufficient; there is an imperative to overhaul it entirely.

Echoing these sentiments in the “Manifesto of the Communist Party” (1848), Marx, alongside Friedrich Engels, emphasized that establishing a democracy that empowers the working class is a pivotal phase in the pursuit of socialism. Marx contends that an authentic transformation in the political realm necessitates an equally radical shift in the economic landscape. The continuation of capitalist exploitation hinders genuine democratic fruition. This structural exploitation of the proletariat by those who own production means inherently defines capitalist society as unequal and unjust.

To provide a robust analytical foundation to his critiques, Marx penned “Capital” in 1867. This magnum opus meticulously deconstructs bourgeois society, offering analytical tools to understand and challenge the dominant capitalist order.

Works by Karl Marx

Let’s take a chronological journey through some of Marx's most influential works, examining the insights they provide and their potential implications for the business world.

1. Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 (Published 1932)

Chronological Position: Written first but published much later.

These early writings are instrumental in understanding Marx's development as a thinker. Even though they were written early in his career, they were not published until 1932. In these manuscripts, Marx discusses his theories of alienation, which posits that under capitalist systems, workers become estranged from the product of their labor. This is especially pertinent today, with discussions about employee engagement and the search for meaning in work.

Implications for Business: Recognizing and addressing worker alienation can lead to more engaged, productive, and satisfied employees.

2. The Misery of Philosophy (1847)

Replying to Critics and Setting the Stage

Here, Marx responds to the ideas of French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Instead of merely critiquing Proudhon, Marx elucidates his own economic perspectives. He examines the nature of commodities, value, and labor's role in the production of value.

Implications for Business: Understanding the value creation process and the role of labor can provide insights into fair pricing, wages, and production methods.

3. Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848)

The Call to Arms

Co-authored with Friedrich Engels, this is perhaps Marx's most well-known work. It serves as a declaration of the communist worldview, critiquing capitalism while also highlighting the potential for a classless society. Its famous line, “Workers of the world, unite!”, encapsulates its revolutionary spirit.

Implications for Business: While many businesses operate within capitalist systems, being aware of potential inequities can inform socially responsible practices and corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives.

4. Wage Labor and Capital (1849)

Deep Dive into Economic Dynamics

Marx delves into the relationship between wages, labor, and capital. He explores how wages are determined and the dynamics of labor exploitation under capitalism.

Implications for Business: This work provides an analytical framework for understanding wage dynamics, helping businesses grapple with fair wage discussions and labor rights.

5. The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)

Politics Meets Economics

While more politically charged, this work looks at the rise of Louis Bonaparte in France. Marx examines class struggle and the role of the state, providing a nuanced view of political power structures and their influence on economic systems.

Implications for Business: Recognizing the interplay between political systems and economic dynamics can aid businesses in navigating complex regulatory environments.

6. Capital (1867)

Marx's Magnum Opus

A foundational text for Marxist economic theory, “Capital” delves deep into the capitalist system's workings. From commodity production to the nature of surplus value, Marx offers a comprehensive critique of capitalist economics.

Implications for Business: This in-depth exploration of capitalist economics allows businesses to better understand the system they operate within, potentially identifying both its strengths and vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

Karl Marx, who passed away on March 14, 1883, was much more than a philosopher. He was a keen observer and critic of the socio-economic shifts of his time. His works, set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing Europe, continue to be essential reading for anyone looking to understand the complexities of societal structures and the dynamics of capitalism.