History of the Cuban presence in Mexico

How historical population movements between Cuba and Mexico began in 1519 when Hernán Cortés sailed from the island to the Mexican coast.

Historical population movements between Cuba and Mexico began in 1519, when Hernán Cortés sailed from the island to the Mexican coast, an event that has already celebrated its 500th anniversary.

That would be the documented beginning if it were not for the fact that some archaeologists and anthropologists believe that there were previous contacts between the Mayans and the ancient island dwellers (formerly known as Tainos, Siboneyes, and Guanahatabeyes), as suggested by the pictographs of the Punta del Este Cave in the old Isla de Pinos and other recently discovered sites, but this point has not yet been definitively resolved, because there are dissenting opinions among specialists.

The conquest of Mexico began in Cuba, specifically in the city of Santiago, where Cortés' expedition, sponsored by the governor of the Island and his "almost" political uncle, Diego Velázquez (who was the carnal uncle of Pedro de Alvarado, one of the main lieutenants of the Extremaduran captain), departed.

Cortés left Cuba to undertake the conquest of Mexico, defeating an empire and enslaving its inhabitants. He set sail from Santiago and made at least one stop in primitive Havana (still located in the south of the Island (before its transfer to the north coast in the already known Bay of Carenas), near the mouth of the Mayabeque River, or in the proximity of the indigenous town of Batabanó, where he supplied his ships.

Amazingly, the first Cuban in Mexico was a natural daughter of the Spanish conqueror, held with a native of the Island, apparently called Leonor Pizarro, a native of the surroundings of the "Ciudad Primada" of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa (founded in 1511), where the Spanish was mayor since 1514 and had an encomienda.

Her name was Catalina, and her father gave her, not her main paternal surname of Cortés, but the maternal surname of Pizarro, which he had already imposed on her indigenous mother, a woman who according to the indications was a Taino Indian, and not Spanish, as some have affirmed, because Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a witness at first sight, in his True History of the Conquest of New Spain, points out that "she was an Indian from Cuba who called herself Doña Fulana Pizarro", and therefore the chronicler must have known her personally.

The Taino Indian has given the name Leonor Pizarro at baptism (Cortés himself asked Diego Velázquez to be her godfather), and Cortés names his daughter as his Spanish mother, and the mestizo was born in Baracoa between 1514 and 1515, during his stay there as mayor. The first official position held by the conquistador from Extremadura was in Cuba, and so began his experience in public administration, as he had not yet been released as a military commander, except for a couple of skirmishes without major significance.

The father legally recognized this girl already at the age of 15, in 1529, and married her to the conqueror Juan de Salceda, although when Cortés died, her stepmother Doña Juana de Zúñiga, Marquesa del Valle de Oaxaca, stripped her of all the goods that her father had assigned to her. It is important to mention her because, in reality, she was the eldest of all the children of the conqueror, the firstborn of both women and men. Her later trace is lost in history, but it is recorded that she first settled in Mexico, following Cortes, and went after him also to Spain, where she was confined in a convent by her stepmother, upon her father's death.

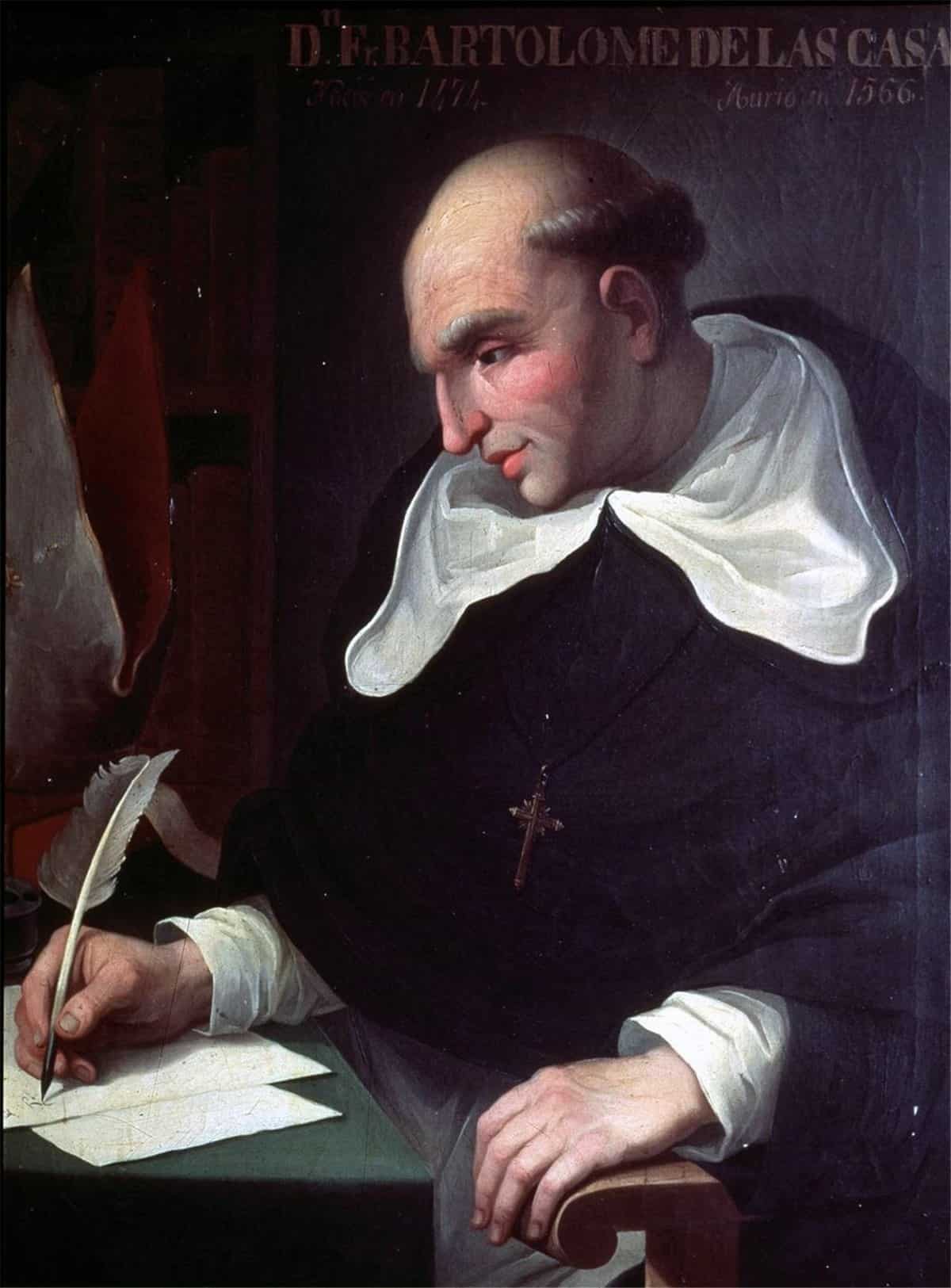

Bartolomé de las Casas, in his History of the Indies, also confirms that Diego Velázquez was the godfather of that Cortés daughter born in Cuba (Book III, Chapter XXVII). And with a certain disdain, I have already said that Bernal Díaz, for his part, says that Cortés had a daughter with "an Indian from Cuba who called herself doña Fulana Pizarro" (Chapter CCIV). In the "Proof of 1550" against her stepmother Juana de Zúñiga, this daughter claimed to have been born in New Spain, although this assertion does not seem true, because of the same age that she declared to have at that time. However, it must also be considered that the island of Cuba was still a part of that time of the continental viceroyalty.

Like many other conquerors, Cortés did not disdain to procreate with non-European females, of any class, and that is why he also had with the Aztec princess Isabel Tecuichpo Moctezuma (1509-1550) a daughter in 1527 (for rape or rape), baptized as Leonor Cortés Moctezuma (recognized by him, but never by his mother), who later married Juan de Tolosa "Barbalonga", one of the founders of the Real de Minas de Zacatecas, and whose descent continues to this day in several houses of the Spanish high nobility titled. Therefore, the first "Cuban" in Mexico had, among other relatives, an Aztec princess as a half-sister.

In total, Hernán Cortés had five natural children (three women and two men) with several American women, and six legitimate children with two Spanish women (three men and three women). They were eleven children in total. In 1529 he obtained the legitimation of his natural children by Pope Clement VII, and he granted all of the goods in his will in 1547, dictated a few days before dying in Castilleja de la Cuesta, near Seville.

It is suggestive that the first Cuban in Mexico was the eldest mestizo daughter of the Conqueror and also one of the first creoles in New Spain, and thus began the intense and constant exchange between Cubans and Mexicans, which continues to this day.

The first abbot of Guadalupe, a rector of the University of Mexico, a bishop of Puebla, and the best sacred speaker in Mexico were Cubans

During the three centuries of the viceroyalty of New Spain, there was a sustained presence of Cubans in Mexico: Since the Colegio Seminario de la Nueva Valladolid began to function in 1540 as Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo, founded by the bishop Vasco de Quiroga (first in Pátzcuaro and since 1580 in Valladolid, today Morelia), it was established that there would be permanently there, besides Creole, mestizo, and indigenous students, at least five young islanders, for which all their expenses were covered: these were the "first Cuban scholarship holders" in Mexico.

When they finished their studies, some returned to the Island, others stayed in Mexico or traveled to Spain to continue the exercise of their professions, as religious or judicial counselors. Something similar happened with the Colegio de San Ramón Nonato in the capital of the viceroyalty, founded by a former bishop of Santiago de Cuba.

Jurisdictionally, the Government of the Island of Cuba was subordinated to the Viceroyalty of the New Spain, and thanks to it, important civil and military works could be carried out as the set of fortresses in the cities of Havana, Santiago de Cuba, and Cienfuegos, for a special tax known as "El Situado de México" that the Royal Viceroyalty Boxes periodically provided to the Spanish administration on the island, and that historian Jacobo de la Pezuela estimates that between 1511 and 1811 added the amount of 168 million 150 thousand 504 strong pesos: "Even the streets of Havana were paved with Mexican stones," it was said.

Several notables of Cuban origin occupied important positions in New Spain from the middle of the 16th century. The first abbot of the Insigne y Real Colegiata de Guadalupe (today Basilica), was from its foundation on July 13, 1747, until his death a famous Cuban sacred orator, Juan Antonio de Alarcón y Ocaña (born in Havana, a doctorate in Avila and died in Mexico on August 13, 1757).

He was not the only one with this pious vocation, as there was an interesting trilogy of Guadeloupe Cubans in the 18th century, such as Francisco Xavier Conde y Oquendo (Havana, December 3, 1733-Puebla, October 5, 1799), José Julián Parreño (Havana, December 11, 1728-Rome, December 1, 1785) and Fray José Manuel Rodríguez, who developed his activities in Mexico between 1754 and 1773, with an abundant printed production, and of whom the New Spanish scholar and bibliographer José Mariano Beristáin y Souza (1756-1817) said in his Bibliotheca Hispano-Americana Septentrional (1816-1821), that it was "one of the most outstanding and universal inventions of its time", and that to him "it was due, in great part, the reform of the pulpit oratory in Mexico".

The first two also received the attention of Beristáin and, later, Manuel Toussaint. Another Cuban, Santiago de Echevarría y Elguezua (1724-1790), was promoted as bishop of Puebla de Los Angeles, the second most important diocese in New Spain, after having been bishop of Havana.

The first Cuban protomedical (that is, the one that trains and qualifies other doctors; therefore, initiator of medical studies in the Island) was received at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, and was the Havana native Francisco González del Álamo y Martínez de Figueroa (1675-1728), member of a large family settled in Cuba, known by the nickname "Chauchau".

He was the author of the one that some believed (although a copy has not yet been found and is only known by references) of the first Cuban print, a medical dissertation about pork being healthy in the Windward Islands, cited by Beristáin (who claimed to have had it in sight), and mentioned by José Toribio Medina as printed in Havana in 1707.

It is astonishing that even today the most pleasantly remembered ruler in the history of the Hispanic colonial rule of three centuries in Mexico, for his great works, his valuable reforms, and the progress he promoted in Mexican lands, was precisely a Cuban: Juan Vicente Güemes Pacheco de Padilla y Horcasitas (Havana, April 5, 1738-Madrid, May 2, 1799), who was the 52nd viceroy of New Spain from October 16, 1789, to July 11, 1794, a position also held before his father, the first count of Revilla Gigedo.

His work was so extraordinary, transcendent, and meritorious in less than five years of government, that he is still known as "the best viceroy of Mexico", and even as "the perfect ruler"; chroniclers summed up his passage through the viceroyalty by saying that when he arrived in the capital of Mexico this was "the city of puddles", and when he left the government he left is converted into "the city of palaces", as it was later baptized by the traveler Charles La Trobe.

Max Henríquez Ureña, in his Historical Panorama of Cuban Literature (1963), relates other very distinguished Cubans in Mexico, such as the jurisconsults Pedro de Recabarren (n. 1655) rector of the University of Mexico; Ambrosio Melgarejo and Aponte (m.). 1741), first hearer in Guatemala and later prosecutor of the Audiencia in Mexico; Felipe de Castro Palomino (1743-1809), several times prosecutor and judge; and José Duarte y Burón (1704-1770), professor at the University of Mexico; men of science such as Marcos Antonio Gamboa y Riaño (1672-1729), doctor and professor of mathematics; and José Escobar y Morales (1677-1737), doctor, and professor at the University, among others.

Henríquez Ureña points out that Mexico was always a magnet for men of thought in Cuba, as a superior center of intellectual activities. Also important is the stay in Mexico of José Martín Félix de Arrate, considered the first Cuban historian, where he completed his law studies at the University of Mexico and as a scholar of the Colegio de San Ramón Nonato. He was the author of Llave del Nuevo Mundo Antemural de las Indias: La Habana descripta... (finished writing in 1761 and first published in 1830), which he modestly described as "rough embryo or malformed sketch..." when he dedicated it to the Havana chapter of which he was a part.

It is worth mentioning that this relationship was bidirectional, because numerous characters of the Viceroyalty of the New Spain also reached prominence in Cuba, as was the case of the military Don Tomás Curiel, "Indian of the Puebla de los Ángeles", who was governor of Castillo del Morro and according to tradition gave his name to a Havana street that was first called "Calle del Indio" and then "de Peña Blanca", approximately in 1750, as reported by José María de la Torre in Lo que fuimos y lo que somos o La Habana antigua y moderna (La Habana, Imprenta de Spencer y Cía., 1857).

Over the years, not only because of its geographical proximity and commercial ties, the ties between Cuba and Mexico intensified and became closer, through many of its most significant characters.