Holy Moly, Much Gold! The Spanish Conquest, Explained

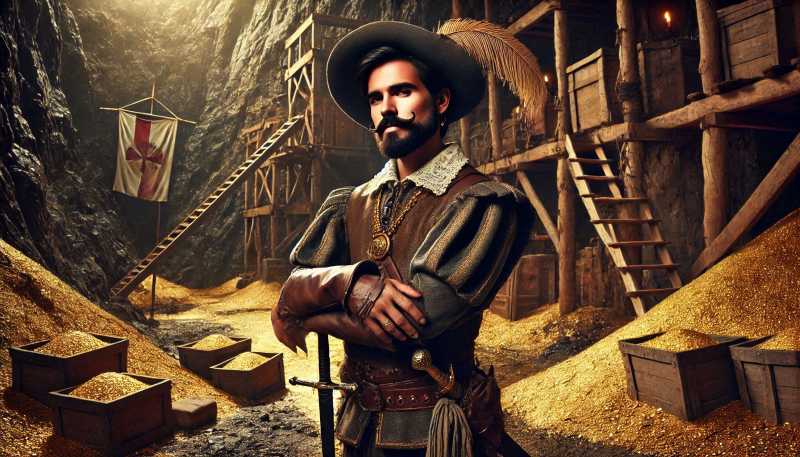

The Spanish conquistadors, a bunch of gold-hungry, God-fearing adventurers, stormed the Americas. They plundered, enslaved, and proselytized their way across the continent, leaving a trail of blood, treasure, and cathedrals.

The Spanish conquest of the Americas—a moment in history so epic, so swashbuckling, and so riddled with names beginning with "New" that one might wonder if the Spaniards were secretly working for a 16th-century real estate agency. Forget about their shiny armor and their dashing capes for a moment; what really set them apart was their unparalleled ability to slap "Nuevo" on just about anything.

It’s a story that starts in 1519 when Hernán Cortés rolled into the bustling metropolis of Tenochtitlán with a modest posse and a look in his eye that screamed, “This place could use a makeover.” By 1521, he and his crew had turned the Aztec capital into what we’d now call a fixer-upper. The resulting mash-up of Spanish and indigenous cultures was, quite frankly, fascinating. Imagine tacos sprinkled with olive oil or Aztec warriors sporting breeches—an uneasy blend that, somehow, managed to stick.