The Wild Theories Behind Humanity's Ancient Relatives

Discover the riveting journey of paleoanthropology, from Darwin's subtle theories to Huxley's bold predictions about our common ancestor. Unearth the intrigue of the Piltdown Man hoax, which fooled experts for decades, and the groundbreaking African fossil discoveries that redefined human history.

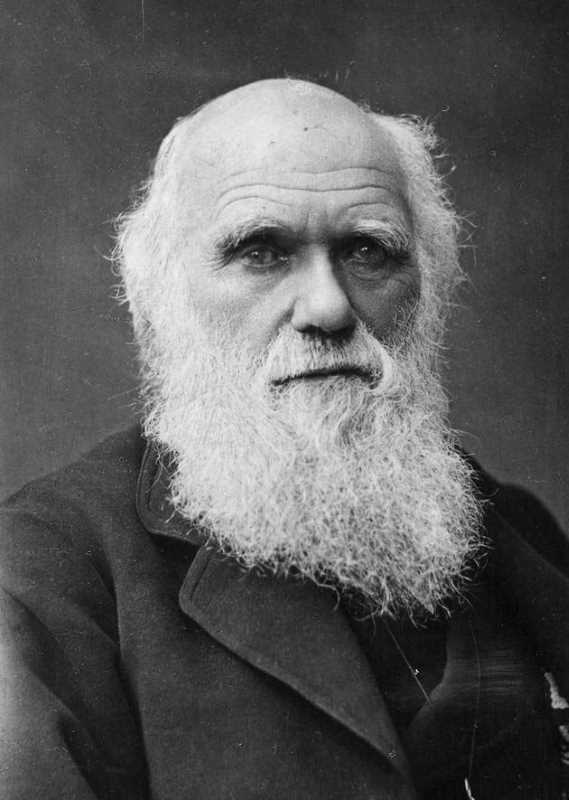

When Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, he ignited a powder keg of debate that still reverberates today. In this seminal work, Darwin proposed that all species evolved through a process of natural selection. While he focused primarily on various forms of life like clams, plants, and birds to illustrate his groundbreaking theory, it was his veiled implication about the origin of humans that sent shockwaves across society.

Darwin tread carefully regarding human evolution, restricting himself to a mere insinuation: “…evolution will be able to clarify the origin of man and his history.” He knew he was stepping into a minefield. The Christian majority of his time found the suggestion that humans evolved from monkeys unacceptable and blasphemous. According to historian Howell, the release of Darwin's book was seen by many as a “frontal and open declaration of war against the teachings of the Holy Scriptures.”

However, this hesitation to directly address human evolution did not deter others in the scientific community from picking up the gauntlet. The boldest among them was Darwin’s contemporary, Thomas Henry Huxley, often dubbed “Darwin's Bulldog” for his vigorous defense of evolutionary theory.

Huxley's confrontations with prominent figures, such as a bishop and the English minister Benjamin Disraeli, were well-documented. He argued that not only did humans evolve, but they also had much in common with anthropoids like gorillas and chimpanzees. Huxley pointed out striking similarities in anatomy, behavior, and more, postulating that these organisms likely shared a common ancestor. Furthermore, he speculated that the fossilized remains of such an ancestor would probably be found in Africa.

The notion that human beings were so closely related to what were considered “lower animals” was a radical and jarring one. It sparked immediate controversy, further dividing the scientific community, religious leaders, and politicians. Despite the uproar, Huxley’s ideas laid the groundwork for the explosive field of paleoanthropology, a science dedicated to the study of ancient human and hominid remains.

As it turns out, Huxley’s prediction about Africa being the cradle of humankind was prophetic. Over time, numerous fossils of early human ancestors—known as hominids—have been unearthed on the African continent. These discoveries have strengthened the argument for human evolution, providing tangible evidence that aligns closely with Darwin's original theory and Huxley's audacious claims.

Dubois' Frustrated Quest for Humanity's Roots

When Thomas Huxley, an ardent supporter of Charles Darwin, announced that hominids had a common ancestor in Africa, he was swimming against the tide. The evidence was scarce, and many theories swirled around early human history like leaves in a windstorm. The first fossil records to be considered were not even from Africa, but rather from the Neander Valley in Germany—a skull and some limb bones that came to be known as the “Neanderthal Man.”

First discovered in 1830, the Neanderthal remains were met with skepticism and a flood of interpretations. Some viewed him as a soldier who had died while pursuing Napoleon's retreating army. Others speculated that he was an unfortunate individual who had suffered from various ailments like rickets and arthritis. The grim appearance of the bones even led some to believe that this was a man deformed by blows to the head. Nonetheless, the academic interest in the Neanderthal man continued, guiding scientists to other fascinating discoveries.

Researchers then turned their focus towards caves and riverbeds, where they unearthed the “Cro-Magnon Man” in southern France. These specimens were in excellent condition, dispelling any doubt about their humanity. Furthermore, the late 19th century saw a surge of archeological activity in Western Europe, enough to compile a comprehensive evolutionary calendar. Contrary to many prevailing stereotypes, this calendar revealed that Cro-Magnon men were not rudimentary beings confined to their caves but were quite like us, capable of complex thoughts, hunting, painting, and tool-making.

While Europe was steeped in its own anthropological wonders, the Dutch physician Eugéne Dubois was setting sail for the Dutch East Indies, consumed by a passion to find the “missing link” between humans and anthropoids like orangutans. His journey led him from Sumatra to Java, where he finally discovered a remarkable fossil: the “Java Man” or Pithecanthropus erectus.

After uncovering a mysterious molar tooth, Dubois discovered a primate skull that was alarmingly human-like. He would later find a femur almost identical to that of a modern human. Convinced that these remains belonged to the same individual, Dubois was ecstatic, thinking he had cracked the code to our evolutionary past. However, his conclusions were met with fierce debates and criticisms, leading him to consult the paleontologist Arthur Keith. The final verdict? The bones were human, not the elusive “missing link” that Dubois had hoped for. Disheartened and frustrated, Dubois buried the remains in his living room and refused to speak on the matter for three decades.

While each of these discoveries—Neanderthal, Cro-Magnon, and Java Man—added pieces to the puzzle, they also raised more questions than they answered. For instance, the Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon men challenged the notion that older human fossils should exhibit a “constant and increasing regression towards primitivism” as Donald Johanson posited in 1982. Meanwhile, Dubois' Java Man remains a fascinating chapter in the chronicles of paleoanthropology, even though it failed to be the missing link he so passionately sought.

The Piltdown Man Hoax that Duped a Nation

In the realm of science, trust is sacrosanct. Researchers rely on accurate data and verifiable evidence to build theories and hypotheses. This trust extends to the public, who look to scientific discoveries for insights into the natural world. However, science is not immune to deception, and sometimes, fraud can severely undermine this trust. One of the most infamous cases of scientific fraud—so audacious it nearly fooled an entire scientific community—was the “Piltdown Man.”

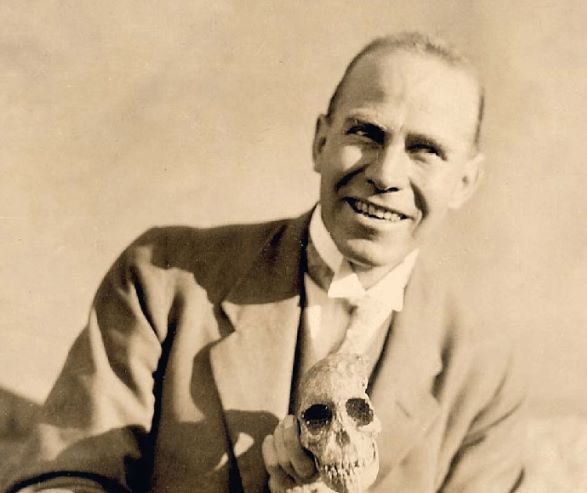

In 1912, a curious event occurred in a gravel quarry in southern England. Charles Dawson, an amateur archaeologist, announced a groundbreaking discovery—a fossilized anthropomorphic jawbone and a modern human skull. Christened as the “Piltdown skull,” this find was significant for a compelling reason: it aligned seamlessly with the prevailing notion of the time that an ancestor of modern humans should exhibit advanced intellectual faculties, yet still retain certain primitive physical traits. This conceptual fossil was warmly welcomed into the scientific fraternity, and especially in England, it was heralded as “The First Englishman,” a being of purported intellectual prowess and English heritage (Johanson, 1982).

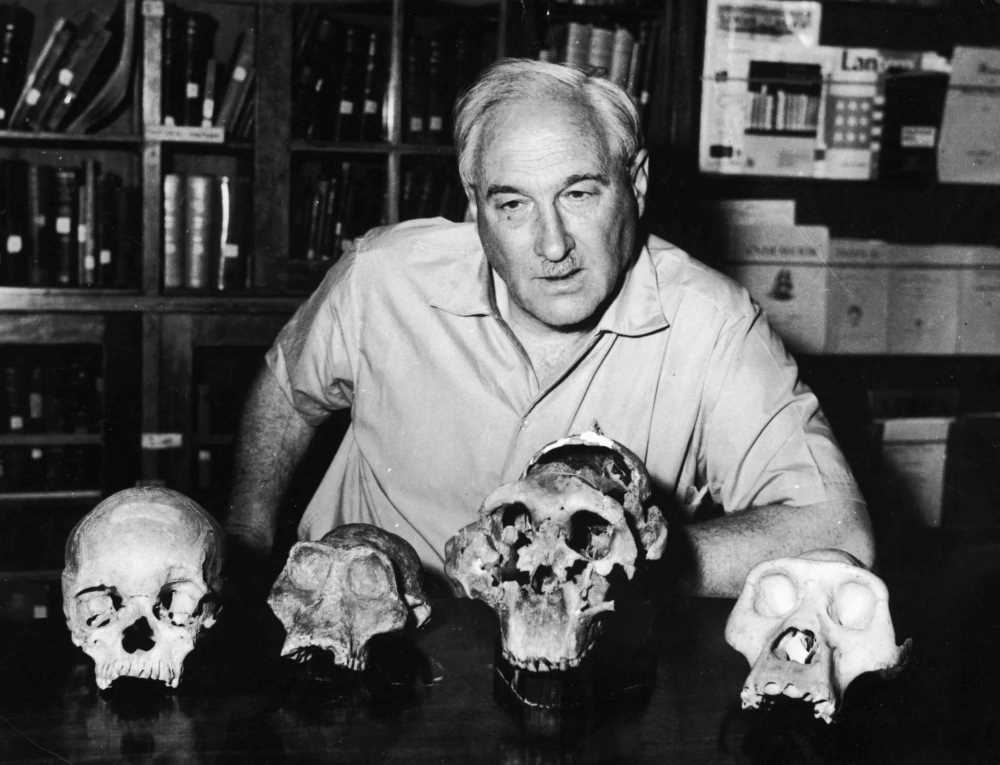

While Piltdown Man was being celebrated and written into textbooks, there were some within the scientific community who harbored doubts. These suspicions were exacerbated when the stewards of the skull maintained an air of secrecy around it. Limited access was granted to other researchers, and close study was restricted. When renowned paleontologist Louis Leakey managed to obtain molds of the skull, he declared it a forgery. Unfortunately, his claims fell on deaf ears and were summarily dismissed.

The masquerade continued for over four decades until 1955, when advanced testing techniques finally revealed the skull for what it was—a skillful hoax. The jawbone was actually that of an orangutan, deliberately modified to resemble a primitive human's, and the skull was indeed that of a modern human. Both were manipulated and artificially aged to appear convincingly old.

While the unmasking of the Piltdown Man relieved some and shocked many, the questions loomed large: Who was behind this colossal deception? Why was it perpetrated? Noted paleontologist Arthur Keith, among others, was left scratching his head, having been taken in by the sham.

Despite decades of investigation and speculation, the identity of the fraudster remains elusive. What is undeniable, however, is the indelible stain left by this scandal on paleontological research. It serves as a stern reminder that even the most rigorous of scientific disciplines can be susceptible to deception and manipulation.

Taung Child Discovery Story

At the dawn of the 20th century, the search for humankind’s origins embarked on a dramatic detour that led a team of researchers to Africa. This set the stage for one of the most exciting and contested epochs in the history of paleoanthropology. It began with an ordinary South African girl's curious gaze at an object resting on a mantelpiece. It unfolded into a journey that shook the foundations of scientific thought, propelling researchers like Dr. Raymond Dart and Robert Broom into scientific immortality.

In 1924, a young South African girl was drawn to what she believed to be the skull of an extinct baboon on her friend's mantelpiece. Intrigued, she recounted the incident to her anatomy professor, Dr. Raymond Dart of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Learning that the skull was procured from a limestone quarry in Taung, Dr. Dart promptly requested any subsequent fossil discoveries from the quarry owner.

In due course, two boxes of fossils arrived at Dr. Dart's residence. The first yielded nothing extraordinary, but the second box held a hidden treasure—a partial skull and an endocranial cast. Dart's exhaustive analysis led to a landmark revelation: the specimen was not a baboon, but rather a six-year-old child-like being with anatomical features suggesting upright walking. In 1925, Dart christened this incredible find “Taung's Child” and categorized it as Australopithecus africanus.

However, this groundbreaking discovery wasn't met with universal acclaim. Influential anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith led the charge against Dr. Dart, vehemently arguing that the specimen closely resembled chimpanzees and gorillas. According to Keith, the notion that the Taung Child could be an ancestor to humans was nothing short of ludicrous. Consequently, the Taung Child receded into academic oblivion, sustained only by Dr. Dart’s unrelenting belief and the support of Robert Broom, a fellow fossil enthusiast and expert.

Broom faced his share of setbacks as well. After weathering professional humiliation, he was left with no other option but to take up a paleontology assistant role at the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria. Undeterred, Broom soon eclipsed even the museum's collection by befriending a local farmer with a private fossil collection. It was during this period that Broom met Barlow, a foreman from a limestone quarry near Sterkfontein, who revealed that fossils were often thrown into ovens. Shocked, Broom convinced Barlow to preserve these invaluable remnants of history.

Just days after their conversation, Broom received an endocranial cast. Swiftly heading to the quarry, he found and assembled fragments of a skull, confirming it as an adult Australopithecus africanus—undeniable vindication of Dart’s original theory.

But Broom's journey didn't end there. In a fateful encounter with a schoolboy named Gert Terblanche, Broom found evidence of a different, robust ancestor. Despite the skull being shattered, thanks to the child's amateur excavating, Broom meticulously restored it and named the new species Plesianthropus robustus in 1938. It was a find that cemented the African roots of humanity, and evidenced a diverse ancestral tapestry with at least two forms of “half ape, half human” hominids.

When Mary Met Nutcracker Man

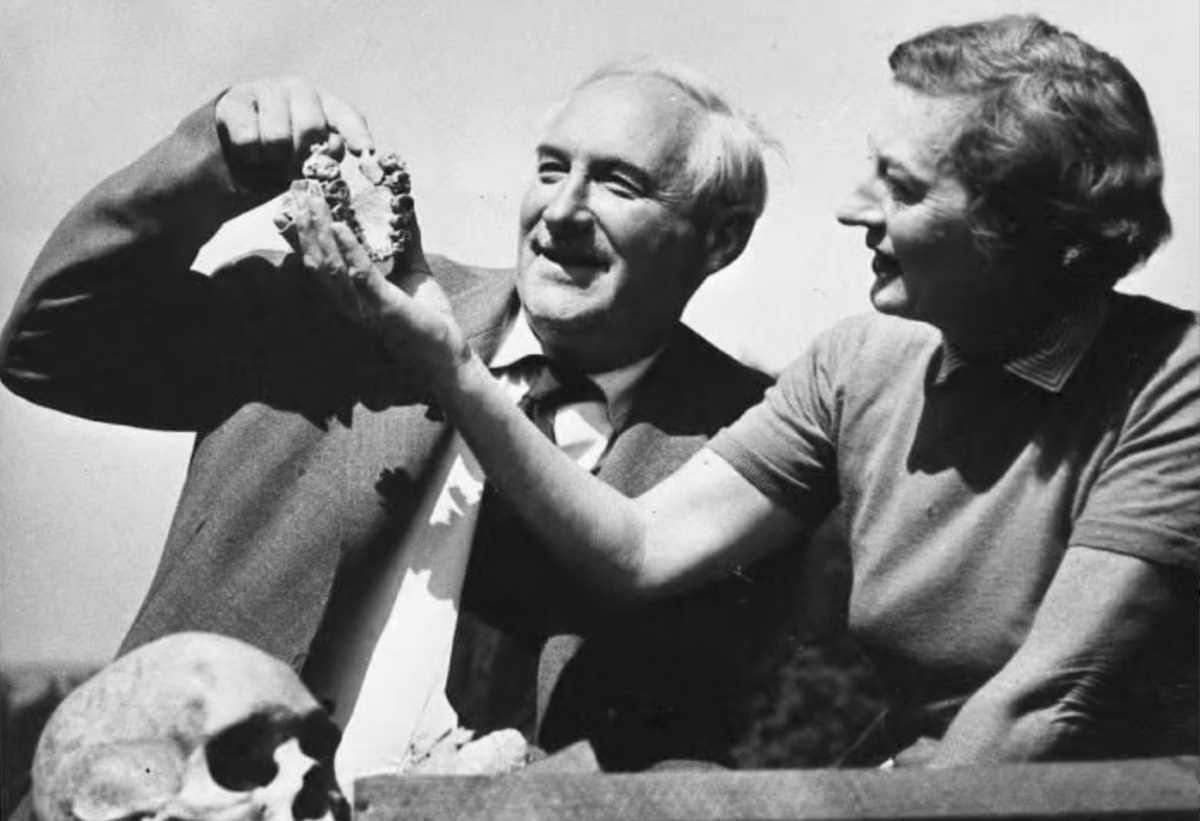

In the sunbaked plains of Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, an excavation in 1959 led to a discovery that would shake the very foundation of our understanding of human evolution. Mary and Louis Leakey, a dynamic archaeological duo, had returned to a site where they had previously found a lone molar. The narrative of this discovery takes a fascinating turn when Louis Leakey fell ill and couldn't participate in the dig, leaving Mary to take up the mantle and set out with their six Dalmatian dogs for company.

On July 17, 1959, Mary ventured to the dig site, her purpose unyielding: to find a significant hominid fossil, a quest she and Louis had been on since the early 1930s. The atmosphere was tinged with anticipation, as she knelt down to brush away layers of earth. In an electrifying moment, Mary’s attention focused on a small fragment that looked quite unlike any rock or pebble in the surrounding matrix. With slow and deliberate movements, she cleared away the surrounding soil, revealing not just one, but several hominid teeth attached to an upper jaw.

What followed was a carefully orchestrated dance of archaeology, as additional bone fragments emerged one by one from the ancient sediment. The skull was finally complete, offering a unique, never-before-seen glimpse into an ancestral past. The couple originally dubbed their groundbreaking find as “Dear Boy,” but the press had their own catchy moniker in mind. They chose to call the specimen the “Nutcracker Man” due to its strikingly large and robust teeth.

However, the Nutcracker Man was not just another example of an already known species; it was something altogether different. Contrary to initial assumptions that the fossil might belong to Australopithecus robustus, its unique features led the Leakeys to classify it as a new species altogether: Australopithecus boisei. This taxonomical decision was not made lightly and involved rigorous scientific scrutiny (Leakey, 1985; Johanson, 1982).

Findings that Set the Tone for The New Millennium

The quest to understand the origins of humankind is one of the most captivating scientific endeavors of all time. New archaeological findings often reverberate through not just the academic community, but also society at large, challenging our notions about who we are and where we come from. Since the early to mid-20th century, the discoveries of ancient hominid fossils have indeed set the tone for the new millennium, opening our eyes to the complexity and richness of human evolution.

When Louis Leakey discovered the “Nutcracker Man” in the Olduvai Gorge of Tanzania, interest in the study of ancient human ancestors resurged. This fossil ignited fascination to such an extent that it attracted the attention and sponsorship of the National Geographic Society. But the Olduvai Gorge had more secrets to reveal. Leakey, along with John Naoier and Phillip Tobias, announced the discovery of a novel species named Homo habilis in 1964. It displayed brain sizes larger than the previously known hominids, like the Austrolopithecines, serving as a bridge between older forms and the Homo lineage.

In 1976, another groundbreaking find came from Mary Leakey, Phillip, and Peter Jones in Laetoli, not far from Olduvai Gorge. What initially appeared to be elephant footprints were later debated to be human footprints, a claim that met with skepticism and debate. Consulting Louise Robbins, an American footprint specialist, led to the initial dismissal of these as bovid footprints. However, after an exhaustive preservation effort by Tim White, the footprint site emerged as one containing fossilized footprints of hominids, adding a new layer of understanding to early human movement and lifestyle.

The discovery of “Lucy” in 1978 in Hadar, Ethiopia, became an iconic moment in anthropology. Led by American paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson, this nearly complete female hominid, belonging to the species Australopithecus afarensis, provided valuable insights into the physical characteristics and probable lifestyle of our early ancestors. Named after the Beatles' song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” this 3.5-million-year-old fossil showed evidence of bipedal movement and sparked imaginations worldwide.

Found in 1984 in Olduvai, Kenya, the “Turkana Boy” remains an extraordinary example of fossil preservation. With a modern, robust body structure and upright walk, the Turkana Boy provides a stunning snapshot of Homo erectus, a species closely aligned with Homo sapiens in the evolutionary tree.

Whether it’s the discoveries in the Dmanisi site in Georgia, classified as Homo ergaster, or the findings at Gran Dolina in Spain, thought to belong to Homo heidelbergensis. The global expanse of these discoveries has only added to the complexity and excitement surrounding our human journey.

Moreover, Meave Leakey's team has uncovered hominid fossils around Lake Turkana in Kenya, dated to about four million years ago and classified as Australopithecus anamensis. These fossils suggest a life around forest environments and bodies of water. Meanwhile, discoveries in Chad postulate the possibility of a western expansion of early hominids, challenging the notion that our early ancestors were confined to East Africa.

Looking Toward the Future

Humanity’s ancient story is ever-changing, molded by new discoveries that continue to fill in gaps, raise new questions, and sometimes even overturn established theories. While the science of paleoanthropology has come a long way, the journey to unravel the complete story of human evolution is far from over.

Indeed, future researchers may look back at our current classifications and theories with bemused smiles, much as we look back at past scientific understanding. Science, after all, is a relentless pursuit of truth, forever adapting as new information comes to light. And in the realm of human evolution, the intrigue remains as deep as our oldest ancestors' footprints in ancient sediment.

Sources: Bernardo Rodríguez Galicia. Homo sapiens y los hallazgos de homínidos. Correo del Maestro, (48), 23-36.