How 'El Mayo' Zambada’s Guilty Plea Could Shake Mexico to Its Core

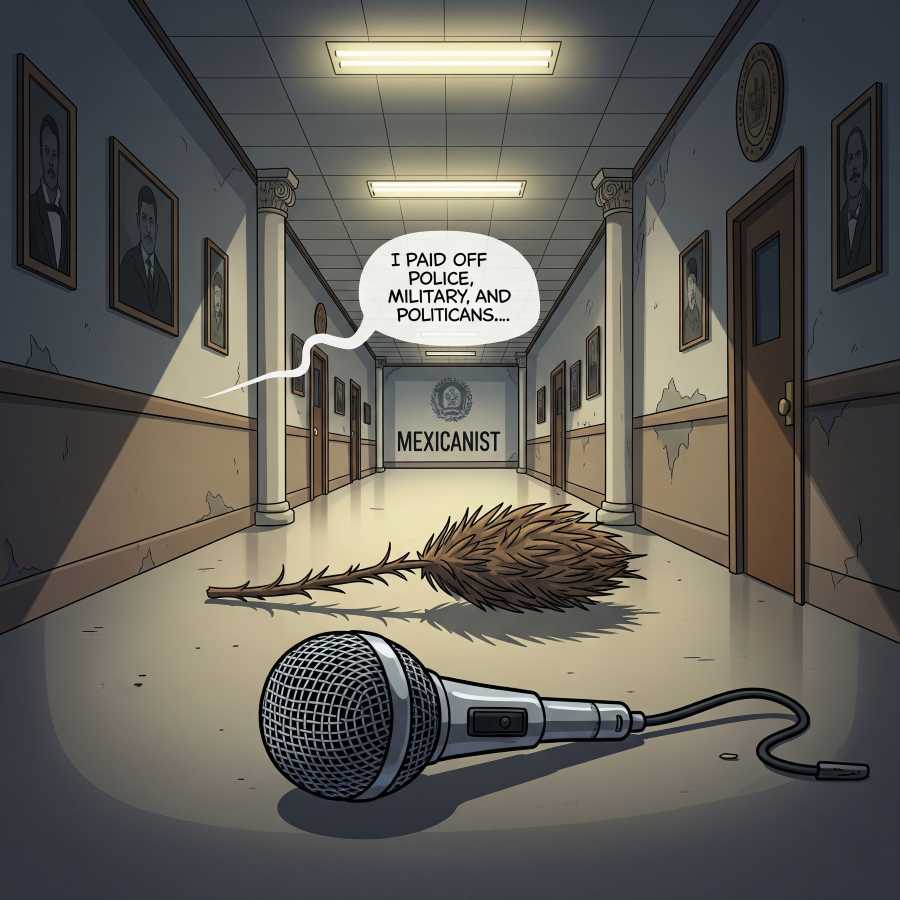

In a Brooklyn courtroom, "El Mayo" Zambada admitted to 50 years of drug trafficking and corruption, confessing he paid off Mexican police, military, and politicians—then vanished into silence.

In a federal courtroom in Brooklyn, New York, on a humid Monday morning, a 77-year-old man in a navy-blue suit stood before Judge Brian Cogan and did something no one thought he ever would.

He said, “Guilty.”

Not defiant. Not silent. Not grandstanding like a warlord facing exile. Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García—the last living godfather of the Sinaloa Cartel, a man who once ruled an empire of cocaine, fentanyl, and fear—quietly admitted he had spent 50 years building one of the most powerful criminal networks in history.

And then, in a voice that carried the weight of half a century of blood and betrayal, he added:

“I paid off police, military commanders, and politicians to operate freely.”

Boom.

That single sentence didn’t just land in a courtroom. It detonated across Mexico like a political neutron bomb.

For decades, Ismael Zambada was the ghost in the machine.

While “El Chapo” Guzmán hogged the headlines—escaping from prison in laundry carts, being hunted by drones, starring in Netflix documentaries—Zambada stayed in the shadows. No flashy interviews. No vanity. Just power.

Born in 1948 in the dusty village of El Alamo, Sinaloa, he started as a small-time marijuana grower. By the 1980s, he was co-founding the Sinaloa Cartel alongside Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán and Héctor “El Azul” Beltrán Leyva. Together, they turned a regional operation into a global narcotics superpower.

But where “El Chapo” was a showman, “El Mayo” was a strategist. He wasn’t interested in fame. He wanted control. And for over 50 years, he got it.

Until now.

Zambada’s guilty plea on August 25, 2025, was not a surprise in the traditional sense. He was arrested in July 2024 in a joint U.S.-Mexico operation so secretive it made the Pentagon blush. But what is shocking is what he admitted—and what he didn’t say.

He pleaded guilty to two counts of drug trafficking in the Eastern District of Brooklyn. That’s it. Two. But the implications? A seismic shift in the balance of power between the U.S. and Mexico, and potentially, the unraveling of decades of institutional corruption.

Prosecutors in the U.S. dropped their push for the death penalty—likely as part of a deal to avoid a messy trial. Instead, Zambada faces life in prison and the forfeiture of $15 billion in assets. That’s 15,000 million reasons to stay quiet.

And yet, he talked.

“For 50 years, I led a massive criminal network… From the beginning until my capture, I paid bribes to police, military, and politicians in Mexico.”

No names. No specifics. But the accusation hangs like a guillotine.

“He’s Not Cooperating,” Says His Lawyer

Frank Pérez, Zambada’s U.S.-based defense attorney, was quick to clarify:

“He’s not cooperating. He won’t name names. He’s not giving anyone up.”

So why plead guilty?

Because he’s guilty.

Pérez’s words were a shield: He’s not talking. The U.S. already has the names. They’ve had them in other cases.

But here’s the twist: If Zambada isn’t flipping, why confess at all?

Legal experts say it’s a calculated move. By pleading guilty, he avoids a trial where prosecutors could have introduced mountains of evidence—wiretaps, informants, seized documents—that might have forced his hand. He controls the narrative. He speaks just enough to seem remorseless, yet powerful.

It’s the ultimate exit strategy: die in prison, but die as a legend.

Back in Mexico City, President Claudia Sheinbaum sat at her morning press briefing, calm as a monk.

Asked if she was worried about Zambada’s allegations, she smirked.

“No,” she said. “Whatever he says, it has to be proven. And the U.S. hasn’t given us any information about his arrest. Not to the Attorney General, not to Security, not to Foreign Affairs. We’re waiting.”**

Translation: We’re not scared. But we’re watching.

Sheinbaum, who has built her presidency on the promise of “zero tolerance” for corruption, now finds herself in a delicate dance. If Zambada’s claims are true—and backed by U.S. evidence—then the rot goes deep. Very deep.

And it didn’t just happen under previous administrations. It spanned decades.

From Vicente Fox to Enrique Peña Nieto, from generals to governors—who took the money?

The U.S. Thinks Mexico Let It Happen

Pam Bondi, the U.S. Attorney General under President Trump, didn’t mince words.

“El Mayo will die in a U.S. prison,” she declared at a press conference. “He operated with impunity for decades because of Mexico’s complacency.”

Ouch.

And then came the kicker from DEA Director Terrance C. Cole:

“We were chasing smoke for years. The cartel didn’t just evade us—it was protected.”

That’s not just an accusation. It’s a diplomatic Molotov cocktail.

Because if the U.S. believes Mexico’s institutions were compromised at the highest levels, it could mean:

- Reduced intelligence sharing

- Freezing of joint operations

- Even sanctions on officials (looking at you, OFAC)

And let’s be real: when the DEA says “complacency,” they mean corruption.

Zambada faces 17 total charges, including drug trafficking, money laundering, and use of firearms. But with the plea deal, there will be no trial. No dramatic courtroom revelations. No witness stand confessions.

His sentencing is set for 2026. But the real drama is happening now.

Because while Zambada may not be talking, the U.S. government already has the files.

And if history is any guide—remember El Chapo’s trial, where he named presidents and generals—those files could be explosive.

Frank Pérez hinted at it:

“The information about politicians? The U.S. already has it from other cases.”

So the question isn’t if names will come out.

It’s when.

Let’s play this out.

Imagine a U.S. court filing drops next year. In it, a DEA affidavit names a high-ranking Mexican official—say, a former defense minister or a state governor—who received millions from the Sinaloa Cartel.

What happens?

- The Mexican government denies it.

- The official sues for defamation.

- The U.S. says, “Here’s the wiretap. Here’s the bank transfer.”

- Protests erupt.

- Trust in institutions crumbles.

And suddenly, Sheinbaum’s anti-corruption legacy is on thin ice.

Because the truth is, Zambada isn’t just a drug lord. He’s a mirror.

He reflects a system that allowed him to thrive. A system where a man from a farming village could build a $25 billion empire—not just by being smart, but by being protected.

The Irony of “El Mayo”

The name “El Mayo” means “The Mayan,” though Zambada isn’t Mayan. It’s a nickname from his youth, when he worked in the fields during the mes de mayo—the month of May.

Now, decades later, he’s facing his final season.

But unlike “El Chapo,” who escaped twice, Zambada will never see Mexico again. His palace in the mountains? Seized. His fleet of private jets? Gone. His network? Fractured.

And yet, in his quiet confession, he may have the last laugh.

Because by admitting his crimes—and implicating an entire system—he forces a reckoning Mexico has spent 50 years avoiding.

Zambada didn’t give interviews. He didn’t write a memoir. He didn’t try to justify himself.

He just said: “I paid them.”

Three words.

And in them, the potential to topple empires.

So while the world watches the U.S. Open, or Bad Bunny’s sold-out residency in Puerto Rico, or the launch of Mexicana de Aviación’s new jets—this is the story that could define Mexico’s next decade.

Not because of guns or drugs.

But because of truth.

And whether Mexico is ready for it… well, that’s a question even “El Mayo” won’t answer.