How Mexico City's Green Lung Caught a Case of the Luxury Flats

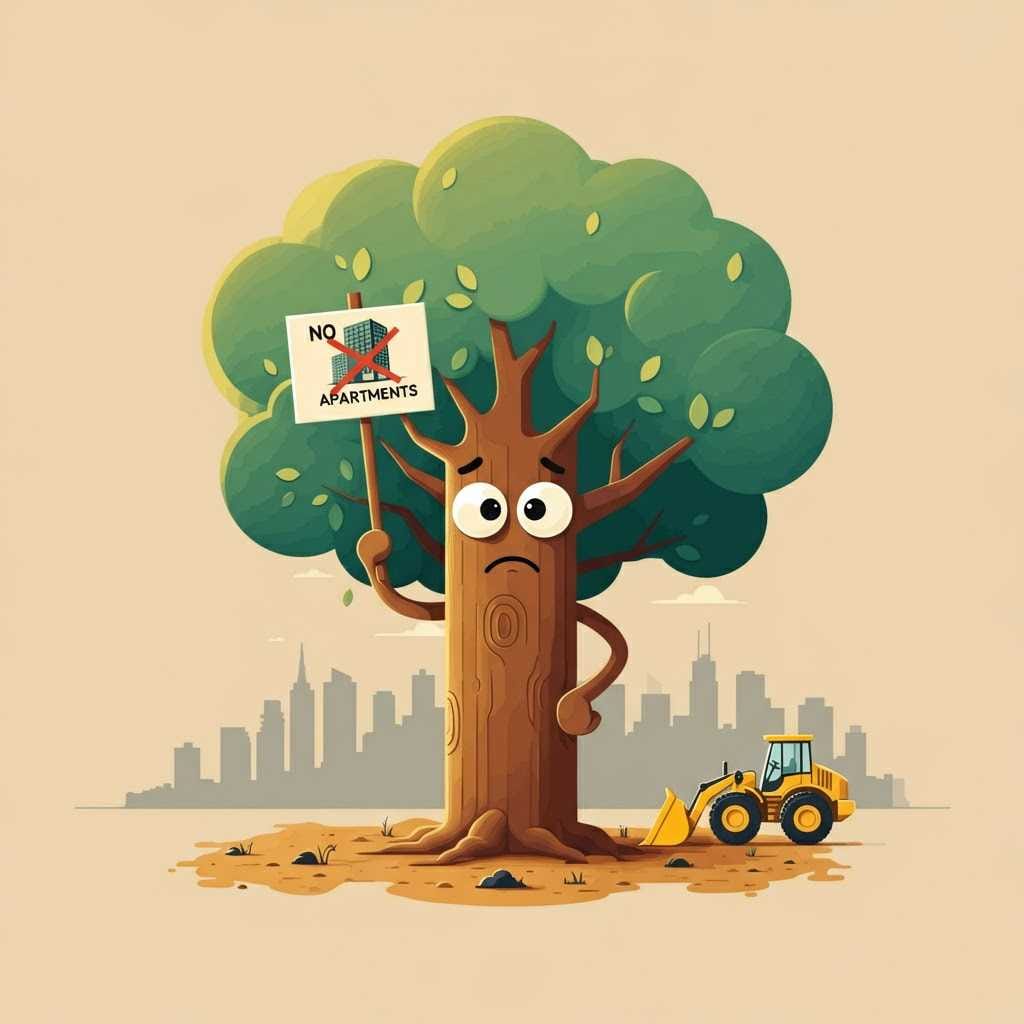

Mexico City's Chapultepec Forest faces a controversial land-use change, as a judge orders 4,799 sq meters to be rezoned for housing. Government officials and activists oppose the move, while real estate developers push for luxury apartments.

In a world where green spaces in major cities are as rare as an honest politician, the fate of Chapultepec Forest, the historic green lung of Mexico City, hangs in the balance. At the heart of this controversy lies a 4,799-square-meter plot of conservation land at Montes Apalaches #525, located in the leafy, affluent Virreyes neighborhood of Lomas de Chapultepec. Normally, you’d think these 4,799 square meters would be left alone, nestled within the verdant sprawl of Chapultepec Forest. But no, because nothing can stay that simple when real estate money enters the frame.

The Fourth District Judge in Administrative Matters recently decreed that Mexico City’s Congress should modify the zoning for this slice of Chapultepec’s conservation land to allow for housing construction. Yes, you heard it right: housing, in the middle of what’s practically a shrine to greenery and fresh air in a smog-drenched city. Naturally, the city’s Head of Government, Clara Brugada Molina, stood up in a fury to tell Congress members, activists, and anyone with ears that the forest is not up for sale—not to luxury apartment developers, not to anyone.

But how did we end up here? Let’s pull back the curtain on this tragicomedy of miscommunication, legal loopholes, and the audacity of those who seem to think a forest’s primary purpose is to be paved.