How the Indigenous Elite Gamed the Colonial System

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire transformed the indigenous power structure. Caciques, the new indigenous leaders, emerged as a bridge between the Spanish and the indigenous population.

New Spain was a place where the allure of conquest collided headfirst with the gritty realities of governance, and where the fate of its early political structures was a jumble of power grabs, shifting loyalties, and jaw-dropping administrative improvisations. In its early years, this embryonic colony didn’t reinvent the wheel—it simply polished it, gave it a Spanish coat of paint, and hoped it would keep turning. And turn it did, at least for a time, thanks to the ingenious co-opting of indigenous power structures.

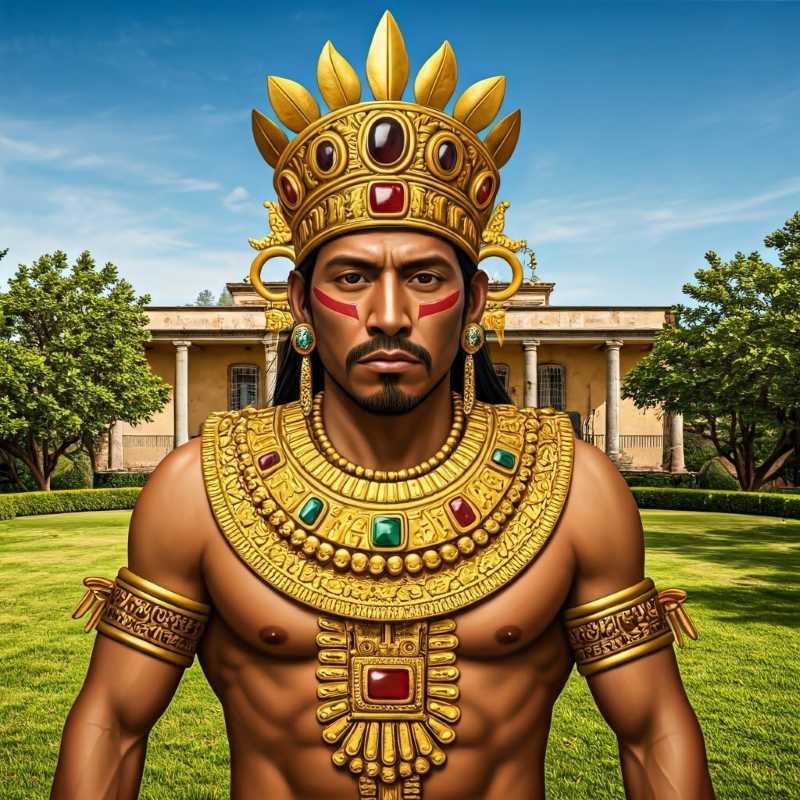

Enter the tlahtoque, the indigenous rulers of the Mexica Empire, now repurposed under Spanish rule into a similar but distinctly colonial figure: the cacique. It’s a title that practically screams, “I am the glue holding this whole mismatched colonial mess together!” The Spaniards, for all their imperial swagger, quickly realized that without these intermediaries, the whole operation would crumble faster than a house of cards in a hurricane.