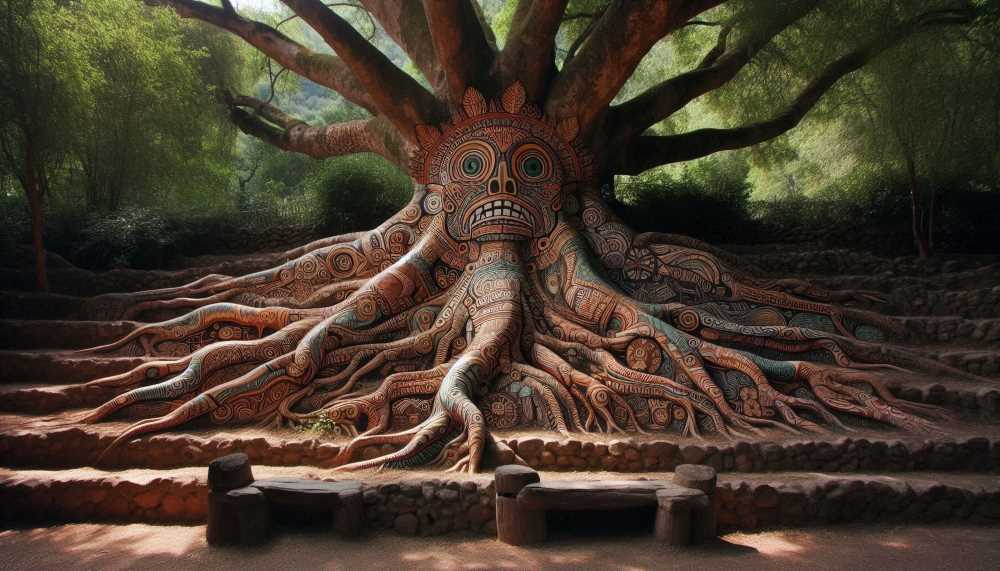

Indigenous Communities Rooted in Tradition, Reaching for the Future

Indigenous communities in Mexico are undergoing rapid transformation. They are adapting to modern life while preserving cultural identity. The article challenges the stereotype of indigenous people as static relics, highlighting their agency and resilience in a changing world.

Cultures inevitably change, and those of indigenous groups in Mexico are no exception. Their members want to be part of the global, mainstream world; they would rather not be left out, said Enrique Rodríguez Balam, a researcher at the Peninsular Center for Humanities and Social Sciences (CEPHCIS) at UNAM.

However, in the political sphere and in some academic sectors, it is often still believed that it is better for them to remain “as they have always been” in certain aspects.