Ivor Thord-Gray: Mercenary, spy, or soldier of fortune?

Ivor Thord-Gray was an anthropologist, as well as an entrepreneur, banker, investor, writer, and academic. He was also a soldier and a man of fortune.

Whether as an officer in the British colonial forces in Africa, as a member of military intelligence linked to the British and American counterinsurgency services in Asia or as a soldier of fortune -who alternatively played the role of revolutionary or counterrevolutionary- Ivor Thord-Gray fought under several flags. He was also an anthropologist and ethnographer, as well as a businessman, banker, investor, writer, and even a university academic. He was thus not only a soldier of fortune but a man of fortune.

What is publicly known about Thord-Gray is not very certain. What I write here is based on three sources that, although contradictory in their details, end up complementing each other. The first is a presentation by Jorge Aguilar Mora to Thord-Gray's book in which he draws a rather unfavorable view of our character: mythomaniac, naive, ambitious, liar, and even traitor to Mexico, are part of the adjectives with which Aguilar evaluates Thord-Gray's personality and performance (although this does not prevent him from saying that "...even so his perception of our country is unforgettable" nor that, despite its flaws, the narrative is "...a complex book of history, ethnography, and interpretation of the spirit of a country and its revolution. ").

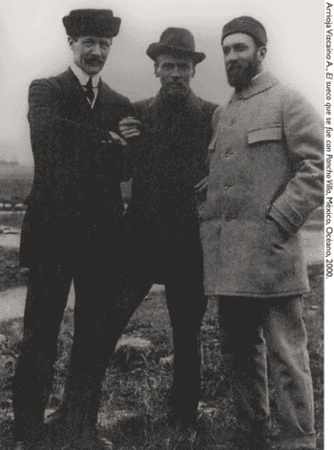

The second source is a book by Adolfo Arrioja Vizcaíno who, with the support of the Swedish Embassy in Mexico, consulted Swedish government archives and Thord-Gray's personal archive. Arrioja is more empathetic with our character, although he does not hesitate to qualify him as a secret agent at the service of British military intelligence and that of his North American allies.

The third source is Internet sites (most of which are based on the book by the Swede Stellan Bojerud - mentioned in some of these sites as director of the Department of Military History of the Swedish National Defense College - published in 2008 under the title Soldat Under 13 Fanor, which in Spanish could be translated as "Soldado bajo 13 banderas" ("Soldier under 13 flags"); several of these sites are not very critical and deal very tangentially with Thord-Gray's actions in Mexico. But then, in accordance with these materials, let us then trace a profile of the author of Gringo rebel, the book we address here.

Although his name has been written in Spanish as Ivord, Ivor, or Ivar that does not matter much, perhaps of greater relevance is that, according to Arrioja, his original surname was Hallström, that it is not known why he changed it and that he was born in 1878 on the island of Björkö, in the Baltic Sea; however, Wikipedia and other internet sources state that he was born in Stockholm on April 17 of that same year.

It is almost certain that his father was of Swedish nationality (although some say that he was a primary school teacher and others that he was an aristocrat) and perhaps that is why Ivor never completely erased his ties with his father's country: his first book on Mexico was written in Swedish; his collection of pre-Hispanic pieces from Mexico was given to a Swedish museum, and he was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts and Sciences.

By contrast, if we focus on the maternal side of his ancestry, the biographical trace is less firm; the sources, without being conclusive, point out that his mother was of British origin, but nothing is certain. Perhaps what we should retain is nothing more than that Thord-Gray had some affective connection with Great Britain and that he justified his foreign accent when speaking English by arguing that he had learned the "Scottish" pronunciation from his mother.

Ivor Thord-Gray has been described as a soldier of fortune, mercenary, and/or spy, by those who consider him a man of few scruples when deciding under which flag and which ideals he should fight. Conversely, in Sweden, the United States, and Great Britain there are those who have considered him as a brave military man who, driven by his fascination for adventure and danger, enlisted in various armies and fought in several wars (i.e., a simplistic remake of the soldier of fortune).

In my opinion, Thord-Gray was above all a military specialist in counterintelligence and counterinsurgency services embedded in the British and American armies who actively participated in combat actions. He had become accustomed to this from his early days as a soldier in the British colonial troops and likewise, from that beginning, his loyalty was devoted first to himself and then to support the advance and consolidation of the capitalist system in the world, something from which he soon learned to benefit.

In 1896, when he was 18 years old, Thord-Gray set out on an adventure. He sailed for nearly two years on merchant ships and then landed in Capetown, the capital of British rule in southern Africa. It is said that there he tried to start a farm and that he was a prison guard, but what is certain is that he eventually joined the cavalry of the British colonial army and soon rose through the ranks of that weapon.

On the internet, it is often repeated that he fought against the Zulus, but in 1897 the power of that great African tribe had already been broken and the British colonial regiments were rather conducting the so-called Second Matabele War (that is, another colonial war waged against the tribes gathered under this name). A little later in 1899-1902, the British were fighting in the same region against people who, like them, were of European origin during the Second Boer War, in which Ivor fought on the British side.

It is also said that he later served as a captain of the mounted police in Kenya (or perhaps Uganda), a territory that was under British rule but in which there were many German settlers. It is not clear why almost all other sources omit what Aguilar Mora points out, namely that from Africa, Thord-Gray went on to India with His Britannic Majesty's Army.

In 1909, Thord-Gray was with the French Foreign Legion in the Gulf of Tonkin region fighting against the Indochinese independence fighters. In 1911, he fought in Tripoli (in present-day Libya) under the flag of the Italian colonial army fighting against the resistance of the Libyans and their allies of the Turkish Empire. From there he went to China, where in 1912-1913 he collaborated with the republican forces of the Kuomintang against the supporters of the imperial restoration in the so-called Xinhai Revolution. From revolutionary China, he went to revolutionary Mexico where he was from 1913-1914.

From late 1914 to 1917, Thord-Gray's performance in World War I is somewhat confusing. On the one hand, internet entries highlight that he was commander of two famous battalions that fought on the western front in France - the 15th and 11th Northumberland Fusiliers with the ranks of captain and lieutenant colonel respectively - for which Thord-Gray received several decorations. However, Aguilar Mora tells us otherwise:

...his service [in the British army of the Great War] lasted barely a year or a year and a half. Mysteriously, he was discharged without honorable discharge before the end of the war. The reason for his dismissal is not hard to imagine: the Great War could not be compared to the campaigns in Algeria, Tripoli, South Africa, the Philippines, Indochina, or Mexico, except insofar as militarily it drew on the technical and strategic resources tested in those lesser conflicts. But there was no place in it for the spirit of independence and adventure to which men like Thord-Gray stubbornly clung. The English army could not allow that he wanted to wage war as if he were in another of its chivalric and nineteenth-century enterprises ... The mystery may lie in the fact that he was not assigned to another army corps or simply disciplined. But perhaps that is precisely the proof that in reality, Thord-Gray did not have, and never had English nationality.

Whether or not he had that nationality, the next thing Thord-Gray did was to go to the United States. According to Aguilar Mora, since June 1916 he had been negotiating with the U.S. government -at that time still neutral- the creation of a volunteer corps of British descent that would enter the war on the side of the British. The lack of communication between the American intelligence services led some to consider him a spy in the service of the German Kaiser, for which reason he was closely watched.

In order to ingratiate himself with the gringo army, he made a short trip to Mexico8 supposedly with the purpose of obtaining information, since at that time the Punitive Expedition under the command of General John Pershing was pursuing Pancho Villa in Chihuahua. Thus, Thord-Gray managed to meet with his friend Colonel Miguel Acosta, who had been his comrade-in-arms in the Carranza army. Aguilar Mora is emphatic in prosecuting this episode:

By early October he was back in the United States, where he now offered military intelligence on the Mexican army and also requested employment as a guide in case the United States invaded Mexico. One could not be more treacherous.

During the same period, Thord-Gray pursued another of his professional facets working as an ethnographer for the Museum of Natural History in New York. Then, in 1918, he enlisted, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, in the Canadian expeditionary corps that was sent to Siberia to support Admiral Aleksandr Kolchack's White Army, which was trying to crush the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. By November 1919, Thord-Gray had become so committed to the anti-Soviet counterrevolution that he was promoted to major general and appointed liaison between the Siberian government and the Allied expeditionary troops (with soldiers from Britain, France, the United States, Japan, and Czechoslovakia); he also obtained a noble title from the tsarist aristocracy.

At that time he was entrusted with the mission of transporting by train a treasure that the White Russians were taking with them on their retreat to the Siberian port of Vladivostock. It has been said that knowing that the Whites were already losing the war, Thord-Gray got his hands on some of the gold he was guarding. He was wounded and fell prisoner of the Red Army. Years later, recalling this episode at the end of his book Gringo rebel, he recounts it thus:

In front of me was another war that everyone believed would be over before I could reach England. That war which later became known as World War I, which President Wilson called 'the war to end all wars,' did not end for me until 1920, when, as a wounded prisoner of the Bolsheviks, I got out of Siberia, thank God and thanks to a very decent and considerate Red commander.

In 1920 he participated in a military coup that overthrew President Gómez in Venezuela and ended his life as an active military officer -at the age of 45- when he intervened in an unsuccessful attempt to restore the monarchical regime in Portugal. In 1926 he published a second book on military subjects, Strategy and Tactics For the 9th Coast Defense Command, which was used as a textbook in some American military academies.

From 1927 onwards he engaged in another multifaceted series of activities: mine inspector in South Africa, rubber farmer in Malaysia; he founded a bank in New York in 1925 which he sold a few years later at a large profit, taking advantage of the financial speculations prior to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In 1934 he became a U.S. citizen and shortly thereafter went to live in Florida, where he was appointed general and chief of staff of the state militia. Beginning in 1939, Thord-Gray was one of the prime movers behind the urban-tourist developments in Key Largo, which today represent real estate values in the millions of dollars. There, in Florida, he wrote Gringo rebel a few years before his death on August 19, 1964, when he was 86 years old.

His books

Contrary to Aguilar Mora, who calls him a traitor to Mexico, Arrioja Vizcaino affirms that Thord-Gray was deeply interested in and loved Mexico:

... despite having lived, suffered, and enjoyed in so many countries, Mexico will always be in his mind, in his memory, and in his imagination. Not only will he return to the country a good number of times, but the three books he wrote during his life on non-military subjects are entirely devoted to Mexico ... Only Mexico, with its troubled history, its serious social inequalities, and its rich anthropological past, inspired this stubborn pilgrim to empty on paper the chest of his many memories.

And indeed, several of his books would deal with Mexico. Leaving aside his military manuals, in 1923 Thord-Gray published Fran Mexicos Forntid, a history of pre-Hispanic Mexico. Later, in 1955, he published the work that would earn him academic recognition in Sweden, a Tarahumara-English dictionary that is also an ethnographic work, since it contains information on customs, religion, herbalism (especially the use of híkuri or peyote in shamanistic ceremonies and cures), legends, ball races (rarajípari) and other aspects of the culture of this famous ethnic group of northern Mexico.

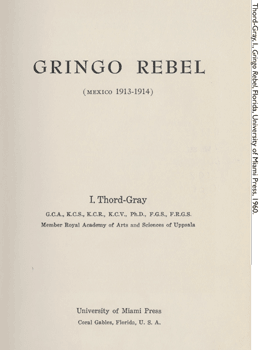

However, the work of Ivor Thord-Gray that concerns us here is another, his account of the time-about a year-he spent in Mexico enlisted in the revolutionary forces fighting against the usurpation of Victoriano Huerta. The first edition of this work was published by the University of Miami Press in 1960. There is also a Spanish translation published by Ediciones Era in 1985 under the title Gringo rebelde. Historias de un aventurero en la Revolución Mexicana 1913-1914 (with the aforementioned introduction by Jorge Aguilar Mora - in English - Gringo rebel. Stories of an adventurer in the Mexican Revolution 1913-1914).

Gringo Rebel

In the preface to his book, Ivor Thord-Gray relates too simply the reasons that encouraged him to visit Mexico and to write a book about his experiences in the Revolution; but perhaps he leaves out others, more complex ones, that also played a part in his decision:

I longed to visit Mexico ever since, as a child, I read about Montezuma and his Aztec warriors, but I did not realize this desire until 1913 when the country was engaged in a civil war. Some forty-five years have passed since I left Mexico in 1914 to join the British Army and the First World War. During that period I have steadfastly refused to write about the Revolution, although I have been requested to do so by friends of mine both in Mexico and in the United States ... The object which encourages me to write at this time is to try to satisfy the apparently growing enthusiasm which the younger generation feels for Mexico, and to encourage a greater knowledge of this country. The reader should bear in mind, however, that my notes reflect what I saw, not yesterday, but half a century ago.

The unconfessed motives that brought him to Mexico will be discussed later; now let us see how it was that Thord-Gray became a rebellious gringo. In October 1913, he was in China, where a mob of foreigners was working to profit from the collapse of millenary imperial China. Thord-Gray tells us that, bored with the slow pace of the Chinese revolution, he was one day having a few drinks of gin at the German Club in Shanghai together with an American agent, another German and a Venezuelan exile who we do not know why he was a Chinese redeemer. The four of them discussed the existence of the great revolutionary movement in Mexico, the audacious bandit-general Pancho Villa, and -most probably- the consequences for the United States of the upheaval in the neighboring country with which it shared a border of nearly three thousand kilometers.

Since the news from Mexico seemed one-sided, and I had nothing better to do, I decided to go take a look. Bradstock [the American agent] bet that the revolution would have been defeated by the time I arrived in the country. I accepted the challenge and immediately booked a ticket to the United States. I immediately visited the Mexican consul, who kindly granted me a six-month special permit for Mexico as an archaeologist and anthropologist. Having thus been granted, I disembarked in the beautiful city of San Francisco at the beginning of November 1913.

Whether it was because he was not willing to lose the bet (according to Aguilar Mora) or because that meeting in Shanghai rekindled his longing to visit Montezuma's country (according to Arrioja Vizcaino), the fact is that Thord-Gray became involved with Mexico and its revolution. By all accounts, it seems very strange that a British ex-military officer should have intended to carry out anthropological research in a country convulsed by civil war. Rather, it would not be unreasonable to think that Thord-Gray went to Mexico on intelligence work for either the British or the Americans; although he omits to tell us anything in this regard, his reference to "knowledgeable Americans" reveals that he at least had contact with espionage experts and political analysts:

In El Paso, everyone considered Villa the undisputed rebel leader of northern Mexico. Everyone was surprised that Villa recognized as First Chief Carranza, whose headquarters were far away, in the state of Sonora. Knowledgeable Americans were of the opinion that this arrangement would not last, as it was difficult to subordinate Villa. Moreover, his nervous temperament made him unpredictable, capricious, and almost extravagant, and he intentionally committed terrible things ... Despite this information I was impatient to meet Pancho Villa, for he had accomplished wonders -almost the impossible- as a cavalry leader, which was of interest to me, who had been trained in the cavalry.

When Thord-Gray arrived in Mexico, Francisco Villa was the head of the Northern Division, the most powerful army of the anti-Huerta revolution. The capture of Ciudad Juarez, in which he employed a famous stratagem that has been compared to the legendary Greek trick of the Trojan Horse, placed him on the world media stage at that time -the press in the United States and Europe- as the most cunning and skillful of the revolutionary generals.

To that media fame, it contributed a lot when a film company -Mutual Film Corporation- offered to pay him for permission to film the movements of his troops (presented to the public in newsreels) and to authorize a movie based on his life. Of course, Villa accepted this deal not only for the money he was getting (and which he used to finance his army) but also because he understood that it was a publicity format that would undoubtedly exert an important influence on the preferences of the American citizens and government about the revolutionary factions.

Ten days after the capture of Ciudad Juarez, when Villa was preparing his troops to fight, because he knew that a strong federal army was on its way to attack him, a guy with a permit from the Mexican consul in China to enter Mexico showed up at his headquarters. That is how the meeting between Villa and Thord-Gray took place, who painted an unfavorable initial portrait of the former outlaw turned intrepid revolutionary commander:

After announcing myself, and waiting half an hour, I was made to appear in front of Villa in a spacious room. My first impression of Pancho Villa, outlaw, bandit, murderer of hundreds, and singular general, was not very bad in spite of his unpleasant reputation and his shaggy and unkempt appearance. He was corpulent, violent-looking, vigorous; his head was large and a little round, his face looked a little puffy. The lips were large and strong, but sensitive. The upper lip was covered with a solid piece of a mustache. The eyes were bloodshot as if sleep-deprived. A hat pulled back hid his hair. He wore soft leather leggings that reached above the knee. His face had a dirty look, but a simian smile, not devoid of benevolence, illuminated his countenance, which otherwise seemed hard and rustic.

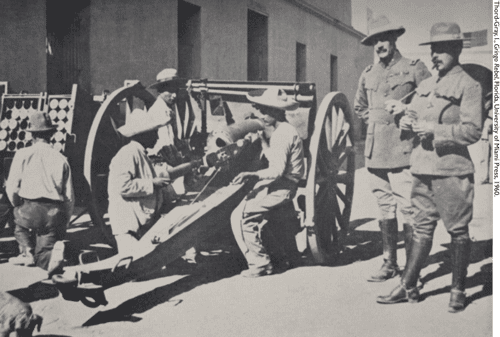

In that first interview, Villa cholericly dismissed Thord-Gray, rejecting without a second thought his offer to join the revolutionaries and accusing him of being a gringo spy and agent of the Huertistas. However, the matter changed when Villa learned that the gringo was offering to repair a couple of damaged cannons that had been taken from the Federals.

In an episode that seems like a novel and we do not know if he is telling us the whole truth, Thord-Gray smuggled the broken pieces to El Paso to have them fixed (he says he took them to the owner of a workshop who sympathized with " the revolt of the peons"), but one wonders if it was not thanks to his contacts with the American army that he was able to fix the damage and take the pieces back to the Mexican side). Thord-Gray was able to have the cannons fired by Villa, who suggested he use a hut on the outskirts of the city as a target:

Thank God, the cannon fired, but the bullet fell short ... To everyone's surprise, four men ran out of the house and disappeared behind the hill ... Villa walked towards me and, to my astonishment, gave me a Mexican hug. The words came from his lips like bullets from a Gatling gun; suddenly I had become his friend and companion ... A few minutes later he proclaimed me his "Chief of Artillery", with the rank of the first captain. My charge consisted of two 75-millimeter field pieces, with no officers or sub-officers under me. There were a few half-savage Apache artillerymen who knew nothing about cannon; some of them spoke only their own language, apart from a little rudimentary Spanish ... Now I was in a quagmire. Joining the revolutionary cavalry was one thing, joining the artillery was another.

The flamboyant artillery chief marched south with the Villista forces anyway, to meet the approaching Federals. Thord-Gray says that before leaving he had the opportunity to have a long conversation with Villa in which they talked about military matters; the career soldier insisting on the need to observe the fundamental rules of military strategy and the revolutionary leader appealing to his natural knowledge of the art of warfare. So there was not a complete understanding, but both reached a certain level of sympathy for the other. That same night, the starving group of so-called "Apache" gunners was joined by two other tribesmen from a different tribe. One of them would become not only Thord-Gray's faithful subordinate and comrade-in-arms, but also his gateway to a fabulous indigenous culture and its mysterious world:

... two proud and handsome-looking natives reported to me as scouts and messengers between General Villa and the canyons. They were pure indigenous of the numerous Tarahumara group, which lives in the highlands of the Sierra Madre in the western part of the state of Chihuahua, and have a great reputation as long-distance runners ... I learned that one of them, named Pedro, was a shaman-healer. After chatting for about an hour, I became so interested that I took out my notebook and made my first notes about the Tarahumara ... Pedro and I became close friends, that is, friends in the indigenous sense of blood brothers. They distrust all strangers. They are closely attached to each other, are as a rule reticent, and have a taciturn, unsociable disposition that the city dweller finds it hard to understand. This distrust may become less tense with time, replaced by a quiet and affectionate understanding, as was the case with Pedro, who often risked his life for me ... Pedro had a staggering knowledge of tribal history, legends, plants, animals, medicinal herbs, and cures. He came from near the village of Urique but had traveled all over the Sierra Madre as a scout for Villa and his guerrillas. He had also worked for some American miners near Zapuri, spoke fairly good Spanish and also a little English which was to prove invaluable to me in the campaign ahead.

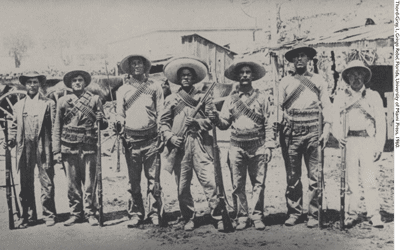

In Tierra Blanca, a railroad station located about 40 kilometers from Ciudad Juarez, in a flat area furrowed by salt sand dunes and vegetation dominated by governadora bushes, the battle between the Villistas and Federales took place from November 24 to 26, 1913. Captain Thord-Gray was astonished at what in his eyes was an encounter fought, on both sides, with an absolute lack of adherence to the canons of strategy, tactics, and military discipline. The villistas were more - it is said 6, 200 - than the federales - it is said 5,500 - but the latter brought more artillery, more machine guns, and more trains. However, against the calculations of the Swedish captain who feared the victory of the Federals because they outgunned and outmanned their comrades, a miracle happened:

Out of nowhere appeared a body of mounted men, like a cohort of Roman cavalry, some three hundred horsemen who charged against the Federal left flank, which was in great distress on our right. The commander of this regiment was a remarkably lucid and resourceful young man. He observed the enemy's extended order and his mounted infantry charged without sabers but without hesitation ... This young lieutenant colonel, a half-breed Apache, illiterate, was a cavalry leader to be admired. His unexpected charge had an overwhelming effect on the enemy. Instead of pointing the machine guns in their direction, the Federals broke ranks and ran back to the hill ...

It is not clear who this young Apache mestizo was who saved the day and turned the tide of the battle, nor how it was that Thord-Gray knew he was illiterate, but it is even less clear why Thord-Gray first enlisted in Villa's forces and after the battle of Tierra Blanca switched to the side led by Venustiano Carranza. In view of the tense relations between the Villistas and Carranza, what led him to make this turn?

According to Thord-Gray's own account, Villa sent him to Carranza, allegedly cajoled by Rodolfo Fierro -Villa's famous subordinate- who hated him for the simple fact of considering him a gringo and wanted to remove him from the esteem of the Centaur of the North; but that explanation seems too simplistic. Wasn't it rather a transfer ordered by other interests, which intended to place a specialist in military matters within a revolutionary side that, in spite of its strategic importance, had not yet achieved triumphs as brilliant as those of Villa and his followers? Was the Swede at the service of North American power groups that saw in Carranza and his people revolutionaries less radical and therefore more controllable than Villa and his followers?

The fact is that a few days after the battle, General Villa commissioned Thord-Gray to go to Tucson, Arizona, for an important shipment of arms and ammunition. Thord-Gray tells us that, facing Rodolfo Fierro's mocking smile, Villa gave him money and told him that, after delivering the shipment in Nogales, Sonora, he should report to Carranza's headquarters in Hermosillo; according to the Swedish military man, Fierro adopted this mocking attitude because he thought that there were many possibilities that the "gringo" would not be able to fulfill the mission and would be captured by the North American authorities.

For Arrioja, the election of Thord-Gray to head the arms smuggling mission from Tucson to Nogales and his transfer from the Northern Division to the Western Division were things that were decided in the high spheres of the U.S. Army; in this regard, this biographer of the Swede who went with Pancho Villa says:

But whatever may have been the feelings that Fierro and Ivar mutually inspired in each other, the truth is that from this incident an obligatory question arises: how is it possible that Villa, suspicious by nature and accustomed to all kinds of deceit and betrayal, could have blindly trusted, and in a matter of life and death for his military future, in a foreigner he had just met and who could easily flee with that high sum of money ... to the United States, or else, to ingratiate himself with Carranza, he could deliver the coveted American arms and ammunition to the Constitutionalist Army? ... The only possible answer to this question is that the suspicious Pancho Villa had received assurances from his agents in El Paso, Texas, that Thord-Gray had a long association with American military intelligence, that he was in Mexico to support the revolutionary forces and was therefore fully trusted. He must also have received indications to reassign him to the Carranza army.

The Mexican Revolution by Thord-Gray

The hypothesis put forward by some, including Arrioja, is that Woodrow Wilson decided to disown and overthrow the regime of Victoriano Huerta because he considered it, in principle, moral duty, and action consistent with the postulates that the United States should disseminate its political and moral principles throughout the world (establishment of democracy, judging States under the same ethical principles with which individuals are judged, implementation of a universal system of law, among others).

Although the European governments accredited in Mexico (with Great Britain at the head and Sweden included) had recognized Huerta, Wilson was not deterred in his attempt to overthrow him and encouraged a new revolution against him, besides keeping alive at all times the option of direct military intervention.

Thus, the constitutionalist revolutionary movement led by Venustiano Carranza and other caudillos, among them Pancho Villa, obtained viability by counting on resources from the neighboring country (some only of a moral nature, such as diplomatic reprovals for Huerta's government, and others more decisive, such as the lifting of the arms embargo for the benefit of the revolutionaries).

There is no doubt that the Mexican Revolution originated in internal causes related, for example, to the unequal system of land distribution and tenure that concentrated the ownership of this fundamental resource in very few hands; to the state of servitude in which millions of mestizo and indigenous peasants found themselves; or to the few possibilities of social mobility that affected the middle classes.

However, it is also possible to consider external causes that had a decisive influence on the course it followed; among these, a very important one would be the North American intervention whose purpose was to undermine certain achievements reached in Mexico during the Porfirian regime: economic consolidation with a strong currency supported by gold reserves; a professional army under the command of officers trained in French and Prussian military academies; international prestige and good relations with Japan, Great Britain, and Germany. To defeat this, the United States supported the opposition first against Diaz and then against Victoriano Huerta.

By the end of 1913, the Woodrow Wilson administration was already determined to disown the Huerta government and Pancho Villa was seen as the natural leader of the anti-Huerta supporters. Therefore, Thord-Gray joined the forces of the Northern Centaur and participated at his side in the battle of Tierra Blanca. But what at the beginning was a favorable opinion about Villa among the Americans (encouraged by the romantic and redeeming images spread by the Mutual film company) changed as a result of the so-called "Benton case", which led to Villa's discredit before the international public opinion.

Faced with the supposedly violent and unmanageable character of the Centaur of the North, the North American government decided to get more involved with Venustiano Carranza and his movement. That is why it is possible that Thord-Gray was sent to support the Constitutionalists with the specific mission of training the army that recognized the supreme command of the First Chief. The Swede who had first gone with Pancho Villa thus ended up marching, from Hermosillo to the Mexican capital, with other chiefs very different from the Villistas.

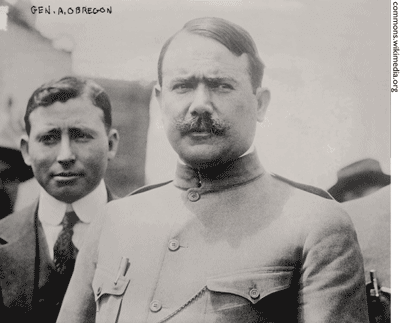

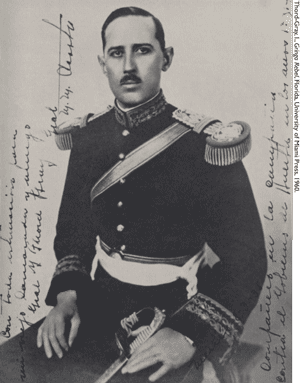

After meeting with Carranza in Hermosillo, Thord-Gray was discharged in the Northwest Army Corps on December 9, 1913, with the rank of the first captain and was assigned to the First Artillery Regiment under Major Juan Mérigo with whom he soon fell out. He was then assigned to the cavalry division under the command of General Lucio Blanco. The mission officially entrusted to him was to give military instruction courses for cavalry and artillery officers; one of his supposed students - who according to Thord-Gray asked for private lessons so that it would not be publicly known that he received this type of instruction - was General Alvaro Obregón, commander in chief of the Division and of whom the Swedish officer left us this portrait:

General Alvaro Obregón was the most competent commander of the revolution. He joined Madero against Diaz, even though at first he did not seem to have any interest or ambition to be a soldier ... He was a visionary man who possessed a great determination to learn everything related to military strategy and tactical problems ... He was brave, cautious and tenacious, endowed with a natural genius for leadership; his talent was combined with the necessary firmness. He was also calm and cool ... he was the one who succeeded in getting Carranza to issue social laws in favor of the peons and indigenous people. The Yaquis and Mayos were loyal to him in every way. His good nature and sense of justice were often overpowered by his indomitable will so that his ambition for power forced him to crush all those who refused to subordinate themselves to him and to obey his orders without reply.

Thord-Gray tells us that in January 1914, while reconnoitering the front on a railroad gun, he was attacked by uprising Yaqui natives; after defeating them, one of the prisoners, "a very handsome-looking native man", asked to be incorporated into the revolutionary forces. This Yaqui was named Tekwe (a word meaning eagle in the Cahita language, spoken by Yaquis and Mayos). He and Pedro will function as a sort of alter ego of Thord-Gray in the rest of the narrative of his adventures. The Yaqui acting as the indomitable and fierce warrior and the Tarahumara as the wise and resourceful shaman.

It is not possible to know how much truth and how much fiction are involved in the roles and actions that Thord-Gray attributes to these characters. Often their omnipresent and unambiguous performance seems implausible, but invariably they constitute an effort by the author to include indigenous Mexico in the history of the revolutionary deed. Sometimes this effort is tainted by unjustified judgments -especially in an anthropologist-, as when he speaks of the Huicholes, whom he describes as faint-hearted, supercilious, and untrustworthy. Overall, despite his appreciation for Tarahumaras, Yaquis, and Mayos, his judgments are based on a classificatory system too imbued with racial prejudices and evolutionism that is not very clear-cut. Thus, about his friend Pedro's skills as a guide, he comments:

I could not help but marvel at the way Pedro always found the right path in the blackest of darkness, which made me conclude that he, like the native tribesmen of Africa or Malaysia, had developed the keenest senses of a wild animal.

Then Thord-Gray tells of an incredible but exciting adventure that, according to him, led him to go into the Sierra Tarahumara and meet the Rarámuri people. There he suffered a severe attack of malaria (a chronic disease he had acquired in Africa); he knew how to cure himself with absolute rest, quinine, and aspirin, but he had lost his first aid kit and could only stop for a few moments to rest. Pedro then offered him the remedy: to chew continuously on hikuri segments. The patient obtained not only relief from his pains, but also unexpected energy that made it possible to continue on the steep trail and even to be able to jump almost three meters to save a deep cliff, which his two indigenous companions crossed several times in order to pass weapons and provisions.

Later, during the night, the effects of the híkuri became more hallucinogenic than exciting and provoked pleasant visions, such as that of being surrounded by beautiful and complacent women. After finishing with the Federals who were pursuing him led by Tepehuanes natives, Thord-Gray spent a few days living with the Rarámuri (he says he attended one of the famous ball races, drank tesgüino and witnessed the ceremony of the yúmari).

Shortly thereafter, Obregón's army passed through the vicinity of the port of Guaymas, which was occupied by the Federals, thus preventing the revolutionaries from obtaining supplies by sea. While conducting an advance patrol, Thord-Gray detected the presence of two Japanese warships supporting the defenders of the port. He says that Tim Turner, a gringo journalist, told him that the ambassador of the Empire of the Rising Sun was then in Guaymas making a pact with the commander of the federal garrison. If this was true, Thord-Gray recounts here one of the very few testimonies of Japanese involvement in the Mexican Revolution (perhaps only Friedrich Katz is the only one who has touched on this little-known matter of Japanese interference in his book The Secret War in Mexico).

Then, Thord-Gray relates the episodes that followed him from Culiacán (late January) to Mexico City (mid-August), fighting in Tepic (a campaign in which he advised Rafael Buelna, the youngest general of the revolution), the Nayar mountains, Acaponeta, Jalisco, Querétaro, and Hidalgo. In all these episodes, the friendship that little by little unites Thord-Gray with the flamboyant General Lucio Blanco and Colonel Miguel Acosta stands out; of course always in the company of his faithful Pedro, Tekwe, and López (the latter a mestizo).

During his stay in the country's capital, taken by the Constitutionalists while Villa and the Northern Division broke the Huertista resistance in Torreon and Zacatecas, Thord-Gray highlights two episodes that, like several others in the book, are, if not completely unbelievable, at least somewhat exaggerated. In the first, somewhat innocuous though quite symbolic, our author relates that while inspecting the National Palace, he, Blanco, and Acosta find the presidential chair used for diplomatic ceremonies. Thord-Gray compares it to the throne Napoleon must have used in his glory days and says:

Before I knew what was happening, Blanco and Acosta pushed me over, forced me to sit in the chair, and ceremoniously waved me over. When I told them that the chair was quite uncomfortable to sit in, Blanco replied, 'Huerta didn't find it very easy to sit there either,' and the three of us laughed in amusement.

The second focuses on the role -according to him decisive- that Thord-Gray played in the deposition of the British ambassador in Mexico. It turns out that England -as well as other European countries- had recognized Huerta's government and its ambassador, Sir Lionel Carden (an agent at the service of the oil magnate Weetman Pearson, Lord Cowdray), had obtained several loans and arms for the dictator; however, with the war against Germany approaching, the British and French allies were forced to subordinate their interests in Mexico to those of the United States so as not to hinder the support they would give them in the inevitable European war.

According to Thord-Gray, the revolutionary generals wanted to arrest and try the ambassador who had so flagrantly supported the Huerta dictatorship and threatened to burn the legation if he resisted. Thord-Gray claims to have played a decisive role in this action by forcing the ambassador to resign, but it is frankly implausible that he made the series of decisions he claims in his book (especially with respect to the Mexican side since it is well known that Venustiano Carranza exercised strict personal control over diplomatic affairs). Be that as it may, before resigning, Sir Lionel delivered to Thord-Gray an urgent cable from London urging the "gringo rebel" to join His Majesty's army in the war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

But before that, in September 1914, Thord-Gray, by order of General Blanco, had left Mexico City for the state of Morelos to fulfill the last of his extraordinary adventures in the Mexican Revolution: to deliver a gift (a Colt 44 revolver with a gold-embossed handle) and a note from Lucio Blanco to the leader of the agrarian revolution in the south, General Emiliano Zapata.

In this other episode, also over adorned, Thord-Gray says that he met a furtive Zapata who remained incognito during an interview between the Swede and Zapatista officers; furthermore, Thord-Gray tells that he climbed the Tepozteco hill and visited the ruins of the Aztec temple on its summit; There he made contact with a Nahuatl shaman who guarded the sacred site (on his return to Mexico, he and his escort of Yaquis and Mayos engaged in a gun battle with the pursuing Zapatistas).

Officially, Thord-Gray received his discharge from the Constitutionalist army on September 3, 1914. The document states:

In accordance with your request, this General Headquarters grants you unlimited leave to separate from the Constitutionalist Army and go to Europe to settle your private affairs ... This is the opportunity to thank you for the magnificent services you rendered to our cause, being at the head of the regiment that I entrusted to your worthy command ... I present you with my attentive consideration and appreciation ... General, chief of the Cavalry Division, Lucio Blanco.

According to Thord-Gray, his retirement from the army was necessary so that the machinations of Obregón and the then Colonel Francisco Serrano against General Lucio Blanco would not advance; both intended to take advantage of Thord-Gray's previous stay with the Northern Division to accuse him of being Villa's spy and thus discredit Blanco as a pro-Villista, thus preventing his possible candidacy for the presidency of the Republic. In this regard, the author writes:

The meaning of Serrano's accusation was obvious. I was under suspicion of being an American friend of Villa; moreover, the direction from which the attack [Obregón] came made it much more serious for Blanco and for me. Serrano, more powerful than ever, was trying to implicate Blanco with Villa through me, as a pretext to get rid of Blanco. To be accused by this man, at this time, was tantamount to a conviction and the firing squad.

So, Thord-Gray left on the Mexican Railroad for Veracruz on September 7, 1914. In the port, then occupied by the American army and blockaded by a gringo squadron, he spent a couple of days with American officers among whom were some of his old comrades-in-arms in the intelligence service and others of high rank, such as the head of the army, Frederick Funston, and the head of the navy, Admiral Nettey. He undoubtedly provided all of them with information on the state of affairs in the Constitutionalist army.

Thus ended Thord-Gray's involvement in the Mexican Revolution. Perhaps more than a simple mercenary or a vile spy, he should be considered a soldier of fortune hired by the U.S. intelligence service, who as such carried out a mission to support the revolutionaries that the authorities in Washington intended to make triumph in the civil war of 1913-1914. Once this mission was accomplished, Thord-Gray left to fight other wars. However, his personal interest in Mexico continued for much longer; he later returned to the country, first to recover the hundreds of archaeological relics he had left in safekeeping in Tula and then to develop the studies on the Tarahumara he had begun with Pedro the shaman. An interesting reflection in the preface of Gringo Rebel shows that his wanderings in the Sierra Tarahumara had deeply touched him:

Never do tourists -and rarely a few educated Mexicans- contemplate the marvelous panorama of Mexico's great sierras. They are picturesque and almost frightening landscapes of unusual beauty. In some places, the steep ravines drop perpendicularly, through solid rock, thousands of feet. When you look down, you experience awe at these tremendous abysses, and you feel very small and unimportant. One has the impression of being in another world and in the twilight, with that darkness below, a shudder can run down one's back, for it reminds one of Dante's inferno.

By Andrés Ortiz Garay, Source Correodelmaestro.com