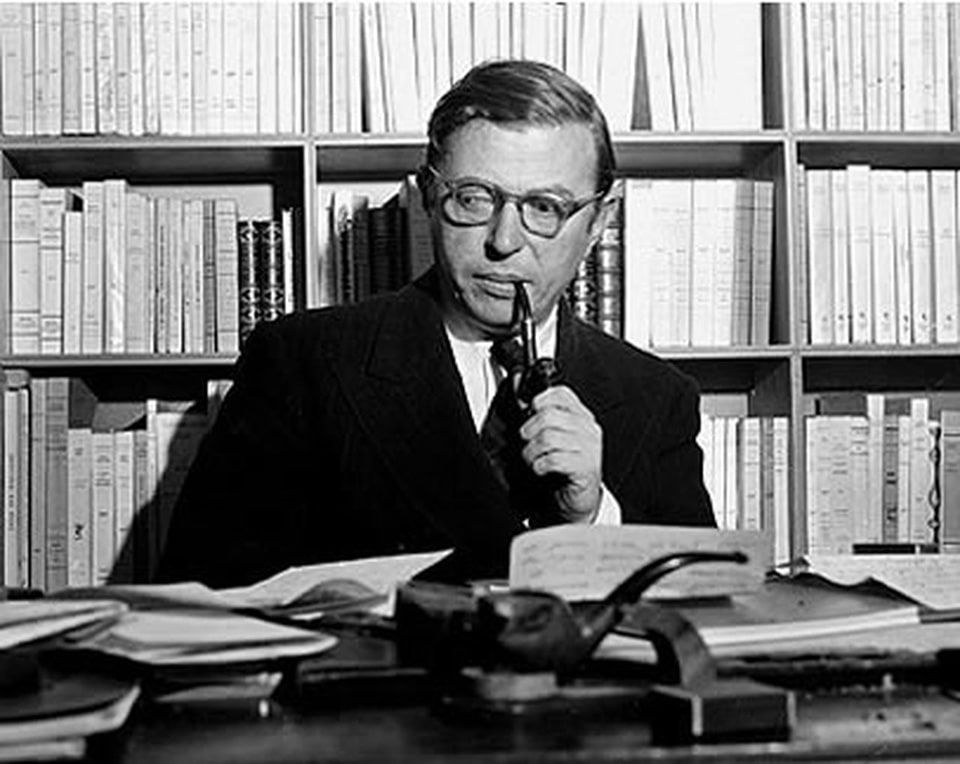

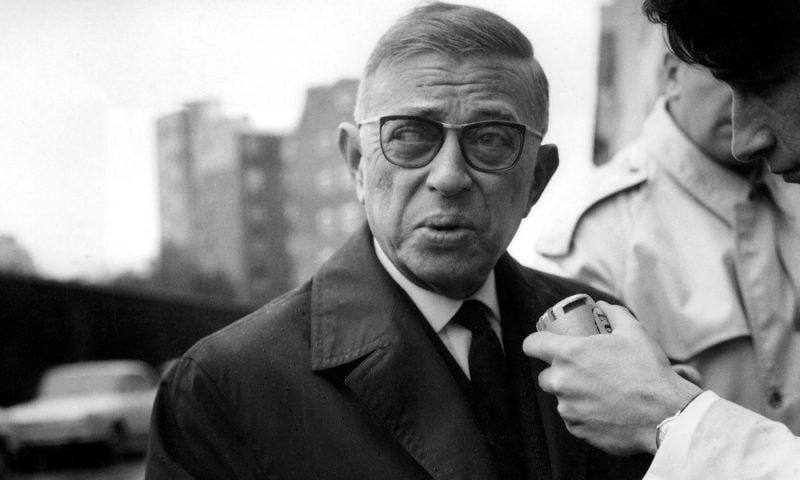

Jean-Paul Sartre, the thinker of freedom

Remembering the French philosopher and father of existentialism, whose thought was fundamental for an unavoidable exercise of the intellectual, collective, and personal autonomy and independence.

Jean-Paul Sartre made philosophy and literature a commitment to social and political struggles. Philosopher, novelist, playwright, and essayist, he was also the father of existentialism: a current that left a deep mark on modern Western thought. He was also a great prose stylist, whose talent made him win the Nobel Prize for Literature, although he rejected it. According to some critics, Jean-Paul Sartre had his achievements and mistakes, but he never - as Louis Althusser said - "accepted the slightest compromise with power" because he was convinced that people come to this world to be free. Thus Jean-Paul Sartre became a philosopher of freedom.

On June 21, 1905, he was born in Paris, France. Orphaned by his father when he was two years old, he was left in the care of his mother and maternal grandparents, whose surnames were Schweitzer. Among them was Albert Schweitzer: an intellectual from the then German Empire at the end of the 19th century, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952. The young Jean-Paul began his basic education in different institutes but finished it with private teachers. His mother remarried in 1917, and they moved to La Rochelle, where the future thinker finished his baccalaureate studies and then returned to Paris to study at the École Normale Supérieure. There, he graduated in philosophy in 1928 and met the woman who would become his lifelong companion, colleague, and lover, who would also become one of the most important intellectuals of the century, Simone de Beauvoir.

During those years of higher education, Jean-Paul Sartre began to write his first texts and to make interesting interpretations that would germinate, later, in many of his most important works. After completing his compulsory military service in 1929, he became a teacher and became strongly interested in one of the most resonant philosophical branches of the time: phenomenology. And he approached it more intensely, hand in hand with Husserl and Heidegger when he moved to Germany on a scholarship he had won to pursue postgraduate studies. From then on, Jean-Paul Sartre reflected on the concept of consciousness, not as something that is comfortably within oneself but, on the contrary, thrown out into the world and even "in danger," as he would later say. It is because Sartre considered consciousness without any conditioning that he also introduced the concept of freedom since, for him, the individual is free. After all, he is free from all determination thanks to this type of consciousness. Some say that with his text The Transcendence of the Ego (1938), Sartre introduced phenomenological thought throughout France.

During the thirties and forties, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a series of works that established his ideas and a whole way of thinking, with a unique and personal stamp, leaving a great mark not only in western philosophy but also in literature, theater, and essays. In 1938 he published one of his most famous literary works, La nausea, in which he already gave an account of his philosophical thinking. In this work of fiction, he divulged some of the principles of that which consecrated him on the stage of modern intellectuals in France: existentialism. This is a current that considers, broadly speaking, that there is no predetermined human nature and that it is the freedom of conscience, of choice, of actions that produce a certain revelation and creation of meaning. Consciousness and world, then, form a single unit and are not separate or detached issues. As some authors say, that consciousness of which Sartre speaks is "a free consciousness and is free to internationalize on that same world that unites it".

The French thinker, in a 1945 conference that he later published under the title Existentialism is a humanism, defined this doctrine as that "which makes human life possible and which, on the other hand, declares that all truth and all action imply a medium and a human subjectivity". Many reproached that this human subjectivity was based on the dark side of life. However, his postulates transformed Jean-Paul Sartre into a celebrity of European thought, since existentialism soon became the fashionable philosophy of the time.

At the outbreak of World War II, Jean-Paul Sartre served as a meteorologist in the French Army. The Nazis took him, prisoner, in 1940, but he managed to free himself a year later. He then worked at the Lycée Condorcet and collaborated with the French resistance newspaper Combat, along with other intellectuals such as the writer Albert Camus, whom he had met at the premiere of The Flies - one of Sartre's most renowned plays. Camus, over time, also established himself as another of the best-known figures in French literature: he published notable works such as The Stranger; The Plague; The Myth of Sisyphus, and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957, which - unlike Sartre - was received with great enthusiasm. In 1964, Sartre rejected the same distinction because he argued that culture should not be conditioned by institutional systems and apparatuses.

Twenty-one years before that polemic over the Swedish award, in 1943, perhaps Sartre's most important work, Being and Nothingness, was published. With this writing, Jean-Paul Sartre deepened the foundations of that existentialist movement, in which he distinguishes some fundamental concepts such as "being-in-itself" (that which is and cannot stop being that to be something else) and "being-for-itself" (the being that can project itself and leave itself; but that also is and manages to be everything it chose). This means that individuals when they choose, are choosing themselves. In other words, we are what we choose to be, we are free to choose and be what we wish to be. That is why, by being free and having an unconditioned consciousness, we can always change; history can also be changed. But for that, as Sartre says, it is necessary to recover that freedom: "Man lives alienated, but before becoming alienated he was free. Alienation is possible because freedom existed before. What we have to do is to conquer it again.

From each of his pages, Sartre was involved in different social and political commitments, ranging from the French resistance during World War II, the end of the war between France and Algeria, the student revolt of May 1968, to the Maoism of his last years. In the seventies, his health began to falter and progressive blindness took him definitively away from reading and writing. He had finished writing one more work of literary criticism, The Idiot of the Family (1971-1972), dedicated to the life and work of Gustave Flaubert.

Jean-Paul Sartre died on April 15, 1980, in his hometown of Paris. Nevertheless, the immense legacy left by the whole of Sartre's philosophy and literature still lives on in different generations of thinkers and those interested in intellectual life. Sartre wrote for them. In one of his many interviews, when Jean-Paul Sartre was asked to whom his works were addressed, what was his real public, the philosopher answered: "Students, teachers, people who are interested in reading, who have the vice of reading".

Source: cultura.gob.ar