How Juan Ruiz de Alarcón Wrote His Way into Spanish Literary History

In the golden age of Spanish literature, alongside names like Cervantes and Lope de Vega, thrived Juan Ruiz de Alarcón—a playwright who overcame immense physical challenges to leave an indelible mark on the theatrical world.

In the bustling streets of 17th-century Madrid, where literary luminaries like Lope de Vega, Quevedo, and Cervantes roamed, there lived a man who defied expectations and shattered stereotypes. This man was Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, a playwright hailing from New Spain, who, despite his physical deformities, left an indelible mark on the world of Spanish literature and theater.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón's life was defined by the physical challenges he faced. He bore the weight of a hunchback, possibly compounded by patizambo, a condition in which one's middle and ring fingers resemble a trident. His teeth, too, were a testament to his physical struggles. Such conditions often led to a life filled with discomfort and the need for concealment.

To cope with his deformities, Alarcón chose a path of pretense and subterfuge. He went to great lengths to disguise his true self, sometimes even resorting to outright lies. One such falsehood was his place of birth, claiming to hail from Mexico City in the Indies when he was actually born in Taxco. He danced around his real age, offering vague statements like “older than… younger than…” to keep people guessing. He concealed his Jewish convert origin and kept his twenty-year-long relationship with Angela de Cervantes nearly hidden from the world. Remarkably, the theme of simulation and deception permeated his works, evident in play titles like “El desdichado en fingir,” “Los empeños de un engaño,” and “La verdad sospechosa.”

Moreover, Alarcón grappled with the idea of double identity and yearning to be someone else, themes reflected in titles like “Mudarse por mejorarse” and “El semejante a sí mismo.” His writing became a cathartic release for his pent-up emotions, a means to confront and transcend the deceptions he wove around himself.

The mystery surrounding Alarcón's true age has puzzled scholars. Recent research suggests that he was born in 1572, not in 1580-1581 as previously believed. His family's move to Mexico City allowed the Ruiz de Alarcón children to receive an education, a privilege they inherited from their wealthy grandfather, Hernán Hernández de Cazalla (Mendoza), a prominent miner whose once-productive mines had ceased to yield riches. This shift in historical context adds depth to the complexities of Alarcón's life and choices.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón's physical deformities, including achondroplasia (dwarfism) and kyphosis, were tangible challenges that he navigated with remarkable resilience. Achondroplasia, which manifests as short limbs, a prominent head, misaligned teeth, and a curved lower spine, often leads to kyphosis. Unlike some individuals whose kyphosis disappears as they learn to walk, Alarcón carried two distinct humps—one on his chest and another on his back—throughout his life. He also contended with curved lower legs, flat feet, and a significant gap between his middle and ring fingers, perhaps contributing to the curious notion of a “trident hand.”

Despite these physical hurdles, Alarcón displayed remarkable intellectual capabilities, earning the description of “normal intelligence.” In his case, it might be more appropriate to say “outstanding” given his dramatic talent and the fact that he pursued law studies. His audacity and unusual physical strength, considering his constitution, became evident when he embarked on multiple transatlantic journeys, risking life and limb in the process.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón's Escape from Obscurity

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, a playwright from the early 17th century, lived a life that, in many aspects, seemed ordinary. He resided in relative luxury, sharing his life with Ángela de Cervantes, a union deemed criminal by the Holy Office due to their lack of marriage. For two decades, they navigated life together, during which they welcomed a daughter, Lorenza de Alarcón. Upon his death in 1639, Alarcón bequeathed his entire estate to his beloved daughter.

Alarcón was not just a silent observer of life; he actively participated in the cultural vibrancy of his era. He engaged in festivals and contests, including the San Laureano celebration in San Juan de Alfarache in 1606. Interestingly, some suggest that he might have crossed paths with the illustrious Miguel de Cervantes during this time. Alarcón also took part in intellectual gatherings, such as those hosted by the Madrid academy of Francisco de Mendoza.

While Alarcón's adult life displayed a veneer of normalcy, his early years were shrouded in mystery. Little is known about the physical appearance of Juan and his mother, doña Leonor de Mendoza. However, Leonor's parents, Hernán Hernández de Cazalla and María de Mendoza, were first cousins, and Hernán assumed the Mendoza surname, possibly to claim kinship with the viceroy Antonio de Mendoza. These well-connected roots positioned them as prominent settlers in Teotalco-Tlachco, descendants of converted Jews. Their wedding in 1572, graced by witnesses of esteemed stature, reflected their social standing.

Curiously, Juan, the firstborn child, did not bear his father's name, Pedro, as tradition dictated. It's plausible that the presence of a congenital deformity—likely achondroplasia, a form of dwarfism—cast doubt on his survival. In this context, the name Pedro might have been reserved for the next male heir, relegating Juan to a secondary position and potentially fostering feelings of exclusion.

The late 16th century was an era devoid of modern medical advancements. In the remote mining town of Teotalco-Tlachco, facing a child's deformity meant only one recourse: concealment and confinement. This practice persisted in Taxco, where the family eventually relocated. Children with disabilities were hidden away in backyards or secluded rooms, out of sight from prying eyes. Thus, it's conceivable that Juan spent his formative years in seclusion, the secrecy necessitated by the prevailing social norms.

The oppressive atmosphere of Taxco, paralleled by the confinement of Juan's youth, may have left him feeling suffocated. However, their subsequent move to Mexico City, a bustling metropolis, liberated the family from the watchful gaze of curious neighbors. Taxco's narrowness mirrored the restriction of Juan's thoracic cavity, which undoubtedly caused him distress.

Juan's childhood confinement found its theatrical parallel in his early work, “La cueva de Salamanca” (The Cave of Salamanca). This play, which some critics date to the years immediately following 1608, depicts the student life of Salamanca with an air of freshness. It introduces Enrico Martínez, a character possibly inspired by a friend of Alarcón's post-Spain return. This cave, a setting in the play, symbolizes Juan's childhood confinement.

In “La cueva de Salamanca,” the cave serves multiple functions. It represents a place for hiding characters during desperate moments, but also alludes to secrecy, encompassing elements like true age, birthplace, and Jewish ancestry, as well as knowledge of the magical arts. For Alarcón, the cave metamorphosed from an unhappy memory into a cathartic tool, a space where he could reconcile with his challenging past.

The Triumph of Deformity and Virtue

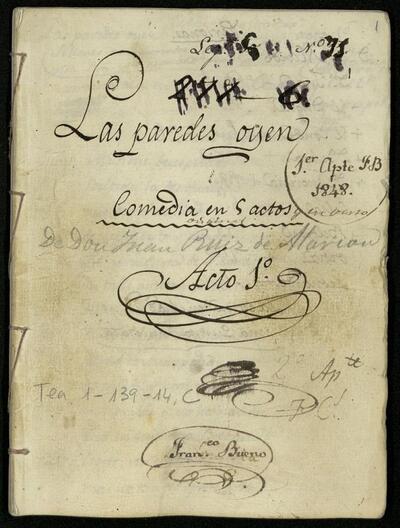

In his urban comedy “Las paredes oyen,” Alarcón presents us with two contrasting gallants—Don Mendo and Don Juan—each serving as a mirror to different aspects of his life. Don Mendo, a dashing yet mendacious character, is likely inspired by Juan de Tassis y Peralta, Count of Villamediana, a notorious courtier and slanderer. Don Juan, on the other hand, is ungraceful and deformed, yet morally upright. Their competition for the lady’s favor serves as a battleground between surface-level allure and deeper virtues, a recurring theme in Alarcón's oeuvre. The comedy's conclusion rewards Don Juan’s sincerity over Don Mendo’s duplicity, offering a consoling resolution for audiences—and perhaps Alarcón himself.

Deformity marked Alarcón's life in more ways than one. Born with a double hump and of diminished stature, he faced rejection from his family and professional circles. Denied a professorship at the University of New Spain because of his physical appearance, Alarcón decided to seek fortune elsewhere. His self-imposed exile to the Iberian Peninsula did not initially yield the professional opportunities he sought. Yet, instead of succumbing to despair, he took to the theater. Despite a lack of opportunities as a lawyer, his relentless efforts in the world of Spanish comedy eventually led him to achieve professional recognition, securing a position as a rapporteur in the Council of the Indies in 1626.

Alarcón’s deformity was a subject of cruel ridicule among his contemporaries, particularly when he was commissioned to write in verse the celebrations for Carlos, Prince of Wales, a high-profile assignment that drew envy and animosity. Prominent figures like Lope de Vega, Quevedo, and Góngora contributed to the caustic rhetoric of deformity, with insults that reduced him to a bestiary caricature. This led to his eventual withdrawal from the theatrical world, finding refuge in his Council position and later, a life of reclusion.

Another significant setback was the sabotage of his play, “The Antichrist,” where a vial of pestilent liquids was used to disrupt the performance. The blame wrongly fell on Lope de Vega, part of an ongoing feud incited by Pedro Mártir Rizo, a historian and poet. This contributed to Alarcón’s withdrawal from the theater, yet his eventual seclusion can be seen as a “moving for the better,” finding peace and fulfillment away from public life.

In his death in 1639, Alarcón was remembered not just for his hunched back but for his significant contributions to Spanish comedy. His will reflected the turn of his heart, arranging for 500 masses for his soul and the souls of his parents, perhaps closing a chapter on a difficult family history.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón's more than twenty comedies explore the existential drama of living with deformities, turning his life’s pain into metaphors of triumph over adversity. By focusing on deeper virtues in his characters, he addressed societal obsessions with physical appearance and outward glamour, demonstrating that true greatness is measured not by how one looks, but by one’s moral integrity and indomitable will.

In-Text Citation: Peña, Margarita. ‘Teatro y Deformidad | Margarita Peña’. Revista de La Universidad de México, https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/3990d774-1258-4265-b050-45ac72198031/teatro-y-deformidad. Accessed 18 Sept. 2023.