The Entertaining Evolution of Mexican Comic Art

Mexico's comic history dates back to the 1920s, and its golden age in the 1930s saw classics like “La Familia Burrón.” While it had its ups and downs, the 1990s brought a rebirth with “Ultrapato” and the rise of Mexican comic studios, promising a bright future for the country's comic scene.

Let me take you on an ink-splattered journey through the captivating world of comics. It's a realm where superheroes soar, mischievous ducks acquire superpowers, and pigs don capes while cities teem with anthropomorphic animals. But before we dive into the tale of Ultrapato and his comic cohorts, we must turn back the pages of history to where it all began.

Long before Spider-Man swung across the skyscrapers of New York, and well before the caped crusader Batman prowled Gotham's dark alleys, comics in their infancy were as old as history itself. In the days of Ancient Greece, amphorae bore intricate drawings that spun stories for the masses. Stained-glass windows in medieval churches regaled the congregation with religious tales.

Yet, the modern comic book as we know it owes its roots to Germany, courtesy of the talented Wilhelm Busch. In 1896, across the Atlantic, Richard E. Outcalt's “The Yellow Kid” graced the pages of a New York newspaper, birthing the term “yellow journalism.”

This was the spark that ignited a comic wildfire. Newspapers began to scramble for comic strips, and soon, the ink-stained stories found their way into the hearts of millions. They weren't just content being part of the Sunday funnies; they wanted more. And so, the first comic magazines were born.

Mexico's Comic Awakening

Mexico, a late bloomer in the comic world, joined the party in the 1920s. North American agencies shipped “entertainment material” to Mexican shores, but it often arrived fashionably late. Mexican talent sprouted like a cactus in a desert, giving birth to characters like “Don Catarino” and “El Señor Pestañas.”

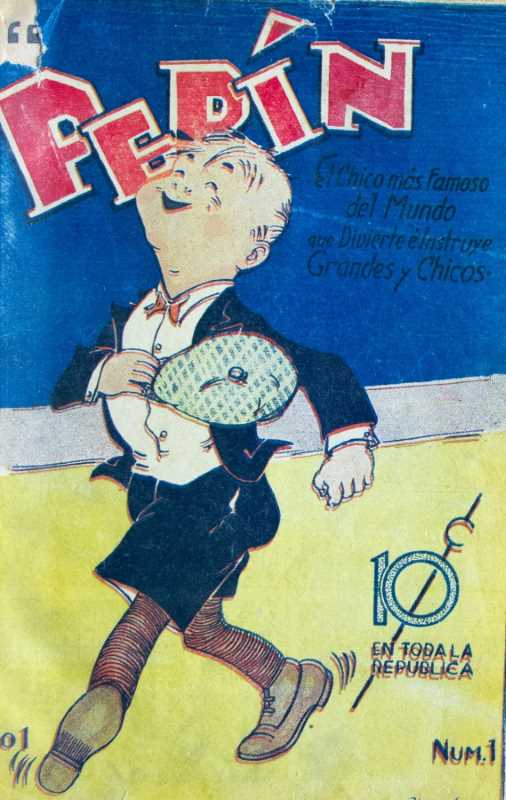

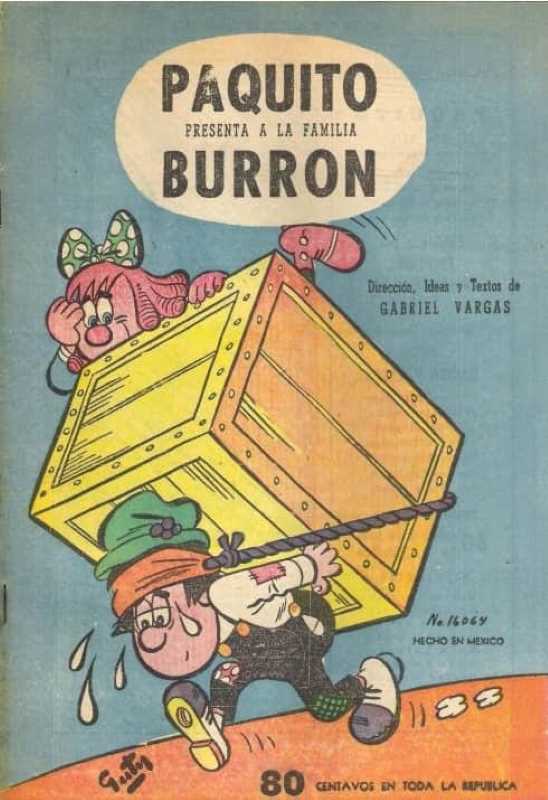

The 1930s were the golden age of Mexican comics. “Paquito” and “Pepín” strutted onto the scene, setting records with hundreds of thousands of daily copies. “Los Supersabios,” a trio of adventurers, performed the most ludicrous feats, while “La Familia Burrón” blended humor with social critique, captivating the masses.

Soon, political comics like “El Chahuistle,” “Los Supermachos,” and “Los Agachados” joined the parade, using satire to slice through the political circus.

The 1950s brought an influx of American heroes like Spider-Man and Superman, but Mexican comics held their ground with “Hermelinda y Linda,” “La Familia Burrón,” and “Los Supersabios.” The period between 1950 and 1960, known as the “silver era,” saw Mexican comics outsell their American counterparts.

But in the '70s, Mexican comics hit a dry spell. A slew of publications like “El Libro Vaquero” and “Sensacional de Luchas” left little to be remembered, except perhaps a fleeting nostalgia.

The Rebirth and Reimagination

In the early 1990s, the “Death of Superman” story shook Mexico and rekindled interest in comics. However, Mexican production remained scarce, prompting an attempt to compile comics by national authors in “Ka-Boom, el Comic.” Yet, it didn't quite live up to its explosive name.

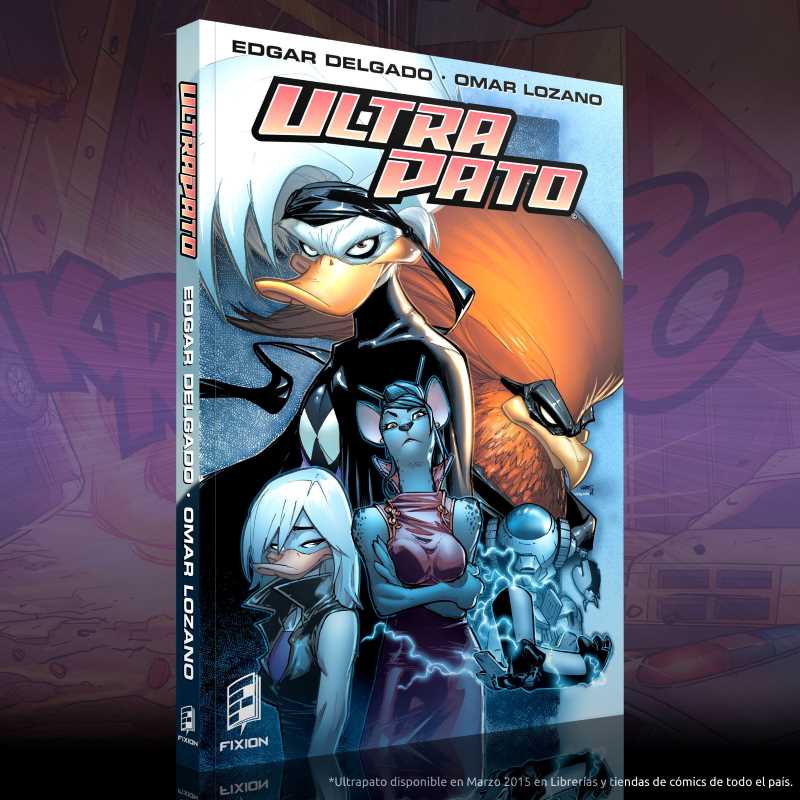

And then, in 1994, in the northern city of Monterrey, a duck named Ultrapato emerged. Armed with extraterrestrial gloves, this feathered champion fought drug traffickers and super-powered foes in a world brimming with anthropomorphic animals. The birth of Ultrapato marked the beginning of a new era for Mexican comics.

Cygnus Studio, the first of many to follow, became a powerhouse in the Mexican comic scene. Ultrapato's adventures were only the start of a wave that brought forth “Valiants” and “Lugo,” stories of vigilantes battling corrupt officials and vampires ending centuries-old struggles.

As Cygnus soared, other studios blossomed across the country. Estudio Entropía brought ancient Aztec gods and superheroes together in “Xiuhcoátl, la serpiente de fuego.” Independent creators like Polo Jasso presented “Cerdotado,” where a pig took on the superhero mantle, breaking free from the chains of parody.

But comics aren't just for entertainment; they're a learning experience. “Odisea 400,” a collaborative effort by Grupo Semper and ADHINOR, took readers on a time-traveling journey through Monterrey's history, seeking to avert a dark future.

The Future of Mexican Comics

One of the main challenges that Mexican comics have confronted is the decline of the mass market that sustained them for decades. Since the 1980s, the proliferation of foreign comics, especially from the United States and Japan, has eroded the audience and the sales of Mexican comics. The cheaper costs of reprinting and translating foreign titles, combined with the perception that comics were only for kids, nearly wiped out the indigenous comic book production in the country.

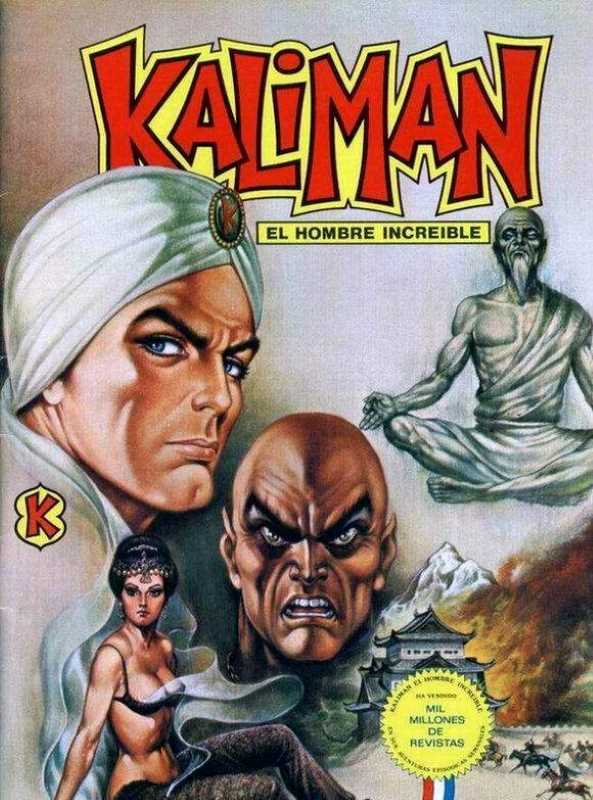

Many of the classic titles and characters that had entertained generations of Mexicans, such as Memín Pinguín, La Familia Burrón, Chanoc, Fantomas, Kalimán, and El Santo, either disappeared or became sporadic and marginal. The comic book industry, once dominated by large publishers such as Editorial Novaro and Grupo Editorial Vid, collapsed and fragmented, leaving only a few independent and alternative publishers to survive.

Another challenge that Mexican comics have faced is the censorship and repression that have limited their freedom of expression and creativity. Since the 1990s, Mexico has experienced a wave of violence and corruption, fueled by the drug war and the political instability. This has affected the media and the culture in general, creating a climate of fear and self-censorship. Many comic book creators have been threatened, harassed, or even killed for their work, especially those who have denounced or criticized the social and political problems of the country.

For example, in 1997, the cartoonist Jesús Blancornelas was shot and wounded by drug traffickers for his investigative journalism. In 2004, the cartoonist Eduardo del Río, better known as Rius, was forced to leave his home and go into hiding after receiving death threats for his satirical comics. In 2015, the cartoonist Rubén Espinosa was murdered along with four women in Mexico City, after fleeing from Veracruz, where he had been harassed by the local government for his critical cartoons.

However, despite these challenges, Mexican comics have also shown a remarkable capacity for resistance and innovation, adapting to the new circumstances and exploring new forms and themes. In the past 20 years, Mexican comics have witnessed a resurgence of creativity and diversity. Thanks to the efforts of a new generation of comic book creators who have embraced the digital and the global, as well as the local and the personal.

These creators have used the internet and the social media to distribute their work, to reach new audiences, and to interact with other artists and fans. They have also experimented with different genres and styles, from the autobiographical to the fantastical, from the realistic to the surreal, from the humorous to the horrific. They have addressed topics such as identity, sexuality, migration, violence, memory, and resistance, reflecting the complexity and the diversity of the Mexican society and culture.

Notable Examples of Mexican Comics

- Bef (Bernardo Fernández), who has created various comics, from science fiction to horror, from crime to comedy, such as El instante amarillo, El héroe, and El ladrón de sueños. He has also collaborated with other writers and artists, such as Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Francisco Haghenbeck, and Tony Sandoval.

- Edgar Clement, who has explored the myths and the realities of the Mexican underworld, such as the drug cartels, the urban legends, and the supernatural beings, in comics such as Operación Bolívar, Kerubim, and Los perros salvajes.

- Jis (José Ignacio Solórzano) and Trino (Trinidad Camacho), who have created some of the most popular and hilarious comic strips in Mexico, such as El Santos, La chora interminable, and Los moneros antiguos. They have also published books and magazines, such as El libro vaquero, La tremenda corte, and La gorda de las galaxias.

- Frik (Ricardo Cucamonga), who has parodied the manga and the anime genres, as well as the Mexican pop culture, in comics such as Cindy la regia, Los chocozombies, and Los supermachos de Rius.

- Bachan (Sebastián Carrillo), who has worked in various genres and media, from fantasy to historical, from webcomics to animation, such as Baal, El Bulbo, and El secreto del Santo Grial.

- Tony Sandoval, who has created some of the most beautiful and poetic comics in Mexico, such as Noche de visitas, El cadáver y el sofá, and Doomboy. He has also published his work in Europe and the United States, winning several awards and recognition.

- Bernardo Esquinca, who has combined the horror and the noir genres, creating a dark and disturbing vision of Mexico City, in comics such as Demonia, Los niños de la noche, and Los escritores invisibles.

From the political satire of José Guadalupe Posada to the popular humor of Gabriel Vargas, Mexican comics have reflected the social and cultural realities of the country, as well as its aspirations and fantasies. These are just some of the many examples of the talent and the diversity of the Mexican comic book scene, which continues to grow and to evolve, despite the difficulties and the obstacles. Mexican comics are a tradition of resistance and innovation, a reflection of the past and the present, a window to the future.