Mexico's Cold War Bogeyman and Its Dirty Little Secrets

The DFS, Mexico's political police, was created in 1947 to protect national security. It became a tool for repression, particularly during the Cold War. The DFS was involved in surveillance, harassment, torture, and extrajudicial killings of political dissidents.

The Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS) is not exactly a name that rolls off the tongue unless, of course, you happened to be on the wrong side of their surveillance. This shadowy organization was Mexico’s answer to the paranoia of the Cold War, a time when the entire planet seemed to teeter between two great ideological blocks: communism and capitalism, with Mexico finding itself caught in the crossfire.

The story of the DFS, however, is not as straightforward as most government security agencies. No, this was an outfit that managed to blur the lines between protecting the nation and terrifying its citizens. And like all good secrets, it was buried for decades—hidden behind layers of redacted documents, whispered in fear, and classified by various Mexican governments. It was, in essence, Mexico's Big Brother: everywhere, watching, listening, and taking meticulous notes, all while quietly pulling strings in the shadows. And naturally, we don't talk about it. Or at least, we didn’t—until recently.

Unveiling the Beast

For years, the DFS was like one of those phantom organizations in spy novels—feared, rumored, and yet shrouded in secrecy. It wasn't until human rights activists, survivors of the DFS's persecution, and historians began piecing together the fragments of its dark past that the picture started to become clearer. And let’s be honest, it’s not a picture anyone wanted to hang in the living room.

Much of the documentation surrounding the DFS remained locked away, classified as confidential—presumably because there’s nothing like a good “state secret” to keep the nasty bits hidden. But in an unexpected twist, the floodgates opened when the DFS-DGIPS collection was made accessible for unrestricted consultation in the National General Archives. Yes, the very organization designed to keep an eye on everyone else found itself under the magnifying glass. And what we discovered was chilling: a brutal, shadowy organization with an operational manual that seemed to have taken inspiration from dystopian nightmares.

Among the treasure trove of released documents is a rather ominously titled file from 1984: “PANORAMAS INTERNACIONAL Y NACIONAL EN CUYO CONTEXTO NACIO Y SE DESARROLLA LA DIRECCIÓN FEDERAL DE SEGURIDAD”—a mouthful if ever there was one. This document is a crucial key in understanding the genesis, structure, and operations of the DFS, not to mention the dark stain it left on Mexico’s national history.

The DFS Emerges

To grasp why Mexico felt the need to create an organization like the DFS, we need to revisit the global tensions of the Cold War. On one side, you had the Americans waving the flag for capitalism. On the other, the Soviets were zealously pushing socialism, with each side trying to win hearts, minds, and governments across the globe. Latin America, ever the political chessboard, found itself right in the middle of this ideological tug-of-war. As Marxist insurgencies began sprouting up like weeds throughout the region, the Mexican government decided it needed a robust defense. Enter President Miguel Alemán Valdés, who, in a fit of nationalistic fervor (or possibly Cold War paranoia), decided Mexico needed its own intelligence service. Thus, in 1947, the DFS was born.

At first glance, the DFS seemed to be just another institution tasked with keeping the president safe, gathering intelligence, and making sure Mexico wasn’t overrun by subversive elements. But as we now know, it was much more than that. It was the Mexican government's secret weapon against dissent, perceived threats, and—most disturbingly—its own people.

The organization, we learn from the PANORAMAS… report, was divided into four essential functions: operations, intelligence, administration, and coordination. Each of these functions was sinister in its own way, especially the “operations” side of things, which dealt with, among other things, “the permanent surveillance of subversive elements and guerrillas,” “elimination of safe houses,” and, if necessary, “the arrest and presentation of kidnappers to the competent authorities.” That’s the bureaucratic way of saying, “we did what we had to.”

More chilling still was the DFS's role in preventing political movements from gaining traction. Think of them as the ultimate killjoy at a student rally, except instead of ruining a good time, they were quelling dissent with an iron fist. Demonstrations, electoral processes, even banking institutions—they were all under the DFS's watchful eye.

And what about intelligence? Well, this was no ordinary fact-finding mission. It was the investigation of national problems as they related to people and organizations threatening the “stability of institutions in the national territory.” That’s code for: “We’re watching you, and we don’t like what we see.” From guerrillas to political activists, the DFS had a file on everyone, and if you were lucky, that was all they had on you.

Che, Castro, and the Mexican Connection

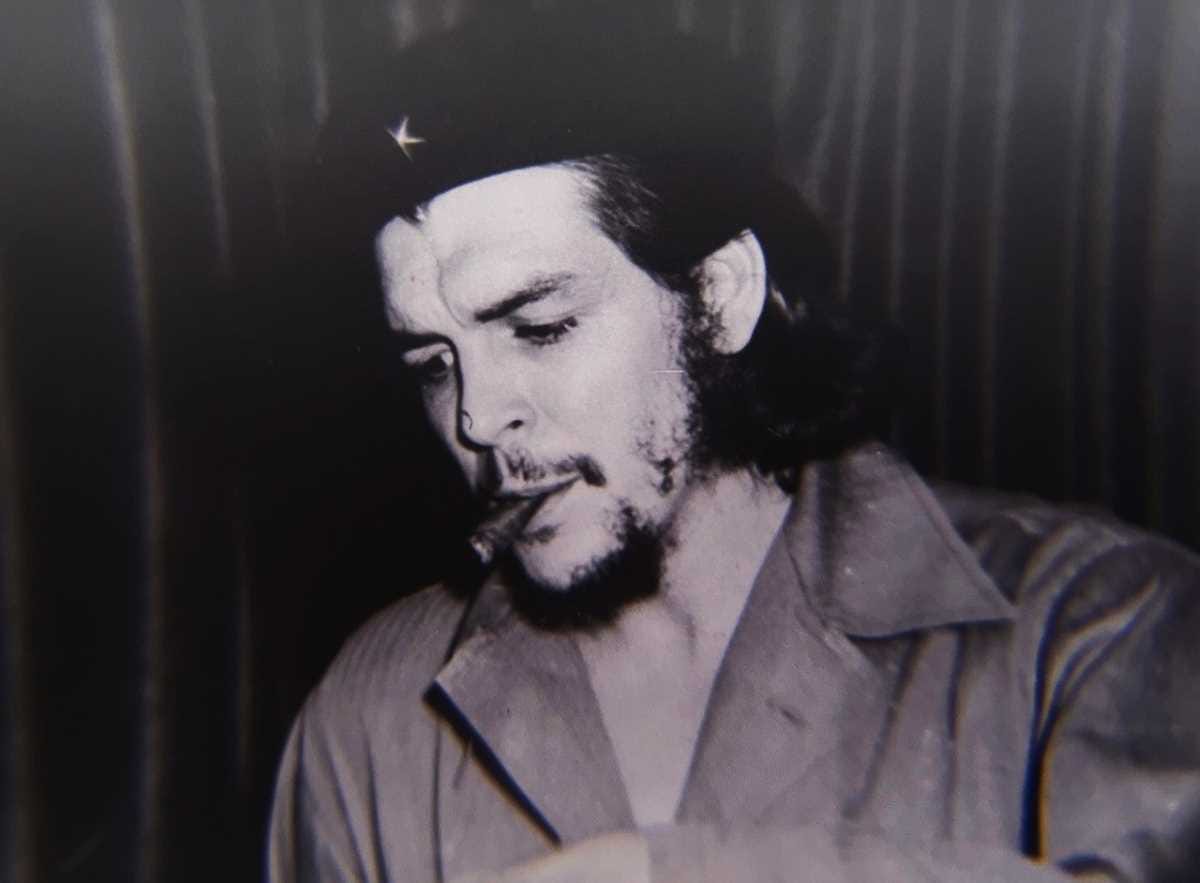

There’s a particularly fascinating—and, frankly, terrifying—element to the DFS’s activities during its early days. In 1956, just as the Cuban Revolution was heating up, a handful of Cuban exiles landed in Mexico, including some rather familiar names: Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos. These were not ordinary refugees. They were men on a mission—a mission to overthrow the Cuban dictator Batista and install a socialist government in its place.

The DFS was naturally suspicious of these Cuban rebels. They began to shadow them like a bad detective novel—following them around, noting their every move, documenting their every conversation. These were the early days of what would become a hallmark of the DFS’s operational style: close surveillance, harassment, and intimidation, with no detail too small to be noted.

As the PANORAMAS… report points out, this period marks the transition of the DFS from a more conventional security force into something far more insidious: a political police force. No longer just a security apparatus focused on protecting the nation from external threats, the DFS now had its eyes firmly fixed on anyone who might dare challenge the status quo from within.

The Closing of an Era, and the Start of Something Worse

By the time the Cuban exiles had slipped out of Mexico and launched their fateful revolution, the DFS was already gearing up for its next chapter. Its transition from national protector to political oppressor was complete, and from the 1960s onward, the DFS would go on to play a central role in Mexico’s own internal struggles. Student protests, labor movements, and grassroots activism were all viewed as potential threats, and the DFS was more than happy to deploy its full array of surveillance techniques and, when necessary, repression.

The DFS would ultimately become one of the most feared institutions in Mexico—an organization whose very existence raises troubling questions about the balance between national security and human rights. In the end, it became a reminder that, in the name of protecting the state, the state can sometimes become its own worst enemy.

The DFS was officially disbanded in 1985, but its legacy lives on in the scars it left on Mexican society. For those who were victims of its surveillance, harassment, and violence, the memories remain raw. For historians and human rights activists, the DFS represents a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked state power, the perils of secrecy, and the fine line between security and repression.

In the 1940s, the Federal Security Directorate was created with the aim of safeguarding Mexican politics and national security from international danger, but years later it would end up taking a radical turn. Credit: AGN

A Story of Revolution, Repression, and Ruin

Now, let’s imagine for a moment that you’re sitting in the tropical heat of Havana in the late 1950s. Fidel Castro and his band of revolutionaries have just stormed the country, kicked out the Americans, and effectively handed a middle finger to Uncle Sam. Revolutionary euphoria is spreading across Latin America like wildfire. It’s as if Che Guevara himself was standing in every town square, handing out rifles and the idea that socialism could sweep aside the corrupt and decadent regimes of the region.

Mexico, always the cautious middle child of the Americas, suddenly found itself in a dangerous ideological crossfire. The Cuban Revolution wasn’t just a rallying cry; it was a grenade lobbed into the geopolitical tension of the Cold War. The Mexican government, caught between the progressive chaos of revolution and the iron-fisted conservatism of the United States, had no choice but to react. Enter stage left: the Federal Security Directorate, or as we’ll call it, the DFS.

The DFS wasn’t your everyday neighborhood watch group. Oh no, it was something far more insidious, with a skill set that would make MI5 look like the cast of Scooby-Doo. This was no happy-go-lucky intelligence agency. They weren’t here to catch criminals or even uphold the law, per se. Instead, their task was to crush any threat—real or imagined—that dared to question the authority of Mexico’s ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). But how did it get this way?

In the wake of Cuba’s communist upheaval, Latin America’s political scene started to look like a Marxist buffet. Armed groups, inspired by Castro’s triumph, began popping up all over the region, like weeds you can’t quite pull out of the garden. Mexico, with its uniquely precarious position, became a breeding ground for such movements. The Mexican government’s first line of defense? The DFS.

But they weren’t just defending the nation; they were protecting the status quo—protecting those in power, and most importantly, protecting themselves. Spying on political opponents, wiretapping, intercepting mail, infiltrating dissident groups—there was no stone left unturned in their pursuit of maintaining control. And in a classic cloak-and-dagger move, many agents posed as journalists, blending into society’s fabric, shaping narratives while pulling the strings from behind the curtain.

By 1965, just a few years after the Cuban Revolution, the situation had escalated to unprecedented levels. Revolutionary groups weren’t just sitting around reading Marx in their mothers’ basements. Oh no, they were taking action, and nowhere was this more evident than in the assault on the Madera Barracks, an incident that tried, and failed, to replicate the famous Moncada Barracks attack that sparked the Cuban Revolution. This was the moment that shook the Mexican government to its core—a full-on guerrilla attack, not in some far-off jungle, but right on their doorstep. The DFS's response? Clamp down harder. If socialist ideas were a virus, the DFS was the government’s attempt to eradicate it through draconian quarantine measures.

Then, in 1968, things took a darker turn. That year, the world had its eyes on Mexico City for the Olympics, but the real story was unfolding in the streets. The student movement, emboldened by revolutionary ideas from Cuba and growing social unrest, dared to challenge the PRI’s authoritarian grip. The response from the government was swift and brutal. The DFS, alongside the army, orchestrated the Tlatelolco massacre on October 2, where hundreds of students were gunned down in cold blood. This was not just a reaction; it was a message, loud and clear—don’t mess with the PRI. National security, it seemed, was not about protecting the people, but about protecting the regime.

But here’s where it gets really interesting. After the massacre, the DFS didn’t pack up its bags and call it a day. This was just the warm-up act. The real terror was yet to come. As the 1970s rolled in, Mexico entered its so-called Dirty War, a period that was as grim as it sounds. By now, the DFS was practically running its own mini-dictatorship behind the scenes. They weren’t just taking on student protesters anymore. They were hunting guerrilla groups like a well-oiled machine of suppression. Groups like the Partido de los Pobres (the Party of the Poor) and the infamous 23rd of September Communist League found themselves in the crosshairs of a security apparatus that had been given one simple instruction: annihilate.

This wasn’t the kind of policing where they read you your rights and give you a fair trial. This was about disappearance, torture, and state-sanctioned murder. The DFS had its very own special ops unit known as the White Brigade, a lovely name for a group responsible for some of the most heinous acts of repression in Mexico’s modern history. These were not your average lawmen; they were merciless enforcers of a regime that was increasingly paranoid and desperate to hold onto power.

And hold onto power they did—at least for a while. But like all good stories of unchecked authority, it was only a matter of time before the DFS began to overplay its hand. In the 1980s, as Mexico started opening its doors to more international scrutiny and a growing human rights agenda, the DFS’s dirty little secrets couldn’t stay buried forever. Their association with drug trafficking and the rampant corruption that had taken root within their ranks was becoming an international embarrassment. Even the PRI, which had once relied so heavily on the DFS to maintain its stranglehold on the country, began to distance itself.

By 1985, the writing was on the wall. The DFS, with its legacy of brutality and lawlessness, had become a liability. It was time to bury the beast. On November 29, 1985, the DFS was officially dissolved, replaced by the General Directorate of Investigation and National Security (DGISEN), a more modern, respectable-sounding institution that would eventually lead to the creation of today’s CISEN, the Center for Investigation and National Security. Of course, this wasn’t a sudden change of heart from the powers-that-be. It was more like sweeping the mess under the rug and hoping no one would notice the bulge.

In the end, the story of the DFS isn’t just a footnote in Mexico’s political history. It’s a chilling reminder of what happens when a government prioritizes political survival over the welfare of its people. The tactics of repression, surveillance, and violence may have secured short-term control, but they also set the stage for future unrest and a loss of legitimacy that haunts the PRI to this day. The DFS may be gone, but the echoes of its brutal reign are still felt, a sobering reminder of the dangers of unchecked power and the lasting damage it can do to a nation’s soul.

In short: the Cuban Revolution may have ignited the spark, but the DFS ensured that Mexico’s Dirty War burned out of control, leaving scars that would take decades to heal.

The Cuban Revolution brought about significant changes in Latin America, one of which was the transformation of the Federal Security Directorate (DFS). Credit: AGN