Segundo Llorente, a Jesuit Missionary from Leon in Alaska

This Jesuit missionary, writer, evangelizer and representative in the Alaska state congress, Segundo Llorente, is one of the historical personalities of the North American state.

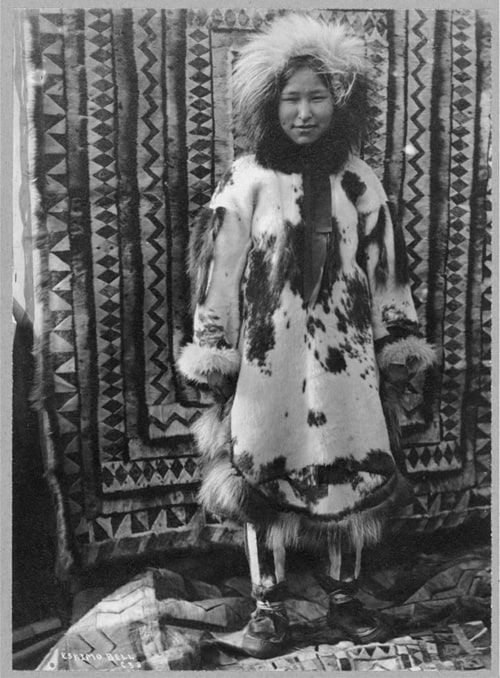

The Jesuit missionary from Leon, Segundo Llorente, arrived in Alaska in 1935 when it was still a territory of the United States. Little explored by Europe and Asia, Llorente's Alaska was characterized by the existence of isolated indigenous communities and by the presence of few settlers.

Segundo Llorente spent more than 40 years as a pastor in his diocese served in two legislatures in Alaska's first government in 1960, and was a co-founder of the 49th state of the United States. This relationship with the Alaskan indigenous people would give him the privilege, at his death, of being buried in a cemetery exclusively for natives (except missionaries with more than 30 years of service with the indigenous).

His early vocation would lead him to choose, already in the novitiate, what would be the most difficult and risky destination of his life: Alaska. In 1930 he would leave a troubled Spain, not to return until 1963 on a triumphant trip to promote missions, and in 1973 to say goodbye to his family. The rest of his life was divided between Alaska, 40 years, and the United States, 14 years.

He fought the loneliness of the Alaskan steppe with his typewriter and his accordion; with his readings and with prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. I estimate that Segundo Llorente wrote more than 20,000 letters to numerous addressees in the five continents. His ten books, his epistolary books, and the articles that appeared in "El Siglo de las Misiones" (The Century of the Missions), set the standard among lay readers and especially among seminarians and novices.

With time he would specialize in directing spiritual exercises, where mysticism, coming from St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross, mixed with his own deep and meditated reflections, gave a really interesting effect. His homilies were not everyday or boring but carried within them strength and contemplation that was not at all common.

His biography takes us, from an early vocation as a religious Jesuit, to a stubborn and stubborn decision to go to Alaska, from his novitiate, insisting to his superiors to forget China (where they wanted him to go) to go to the country of the eternal ice, the impossible mission.

From 1906, when he was born, until 1919, when he entered the seminary, the magic date of 1923, when he entered the Jesuit order, and 1930 when he embarked on the United States, everything was a path of roses, of learning, of retraining and soaking up his homeland, his Spain, which he would not set foot on again until 1963.

In 1934 he is ordained a priest in Kansas and finally, in 1935 he sets foot in his desired Alaska. He would not move from there as a missionary until 1975, when, at the age of 69, he was transferred to the province of Oregon to help evangelize the growing Hispanic colony in the states of Idaho and Washington.

Finally, in 1989, at the age of 82, he died a saintly death at Gonzaga Jesuit University in Spokane (Washington). He is buried in the Desmet Indian Cemetery in Desmet, Idaho.

The culture shock that Segundo Llorente encounters is enormous. First, the English language, since he comes from a small town in Leon (Mansilla Mayor) and has barely studied that language, which he will perfect for five years in the United States before embarking on Alaska. Secondly, the Alaskan language, of which he took great care and became quite proficient.

Thirdly, the contrast between Spain in the 1930s (Republic and Civil War), with the United States during the depression years, and the white paradise of Alaska, where he finds poor Eskimos settled in ancestral traditions, and very rude white settlers.

And it is precisely here where Segundo Llorente's work grows. His work as a social reformer, as an educator, as a transformer of an unjust situation. It is a titanic struggle against a society (the Eskimo), where alcohol, machismo, survival, illiteracy, shamanism, infant mortality, isolation, cold, moral and cultural precariousness, and nothingness prevail; and against society (the white), where seigniorage, slavery towards the weakest, classism, intolerance, individualism, Protestantism, Masonry, atheism, materialism and every man for himself.

Forty years in which he built schools, reformed the magical ancestral imagery of the Eskimos, tried to change the patriarchal and elitist mentality, catechizing children and adults, risking his skin with dog sleds or barges to take God and a minimum culture to the most remote corners of the Alaskan plain.

The reality of that Alaska was tremendous, in a country with 80% alcoholics, with an impossible cold that reached 65 degrees below zero, with corrosive and starving loneliness, where only an iron will or alcohol of 50 degrees could keep people with a minimum of acceptable quality. But Segundo Llorente managed to get hold of it all. He fought, not always successfully, against alcohol in the Eskimos and his white laymen; he tried to educate his catechized people with basic and accessible elements, with images and very practical speeches; he reorganized, in his environment, the impracticable and unhealthy life of the indigenous people, as far as he could, he, who lived very austerely and more soberly than the Carthusian monks!

In the Jesuit archives of the Alaska Province, located at Gonzaga University in Spokane (Washington), there are some unpublished manuscripts of Segundo Llorente, in English and Spanish, certainly interesting in the historiography of Alaska, the Jesuits, and the Eskimos. Father Llorente, who had a lot of time for obvious reasons (very long winters, total solitude for days, darkness in the middle of the year, etc.) had time, besides writing letters and his articles for "El Siglo de las Misiones" ("The Century of the Missions", a Jesuit mission magazine), to portray the character of the indigenous people, the Jesuits and the customs of both.

His facet as a politician, being a priest and missionary, is not without its curious side, since he bowed to the destiny that his acolytes, the indigenous people, wanted him to lead: to have a representative in the Government to defend their rights. It is shocking that a missionary from Leon, a Catholic priest, should be the political representative of the Eskimos of Alaska. He was the first Catholic religious to be a congressman in the history of the United States.

It was 1960, and John F. Kennedy was running in that year's presidential elections, which were very close. Alaska, newly inaugurated as the 49th state of the United States, was going to elect its first congressmen. And the Eskimos had the right to choose their candidate.

They proposed, without telling them, Segundo Llorente as their legal representative before Congress in Anchorage. By the time Father Llorente realizes it, it is too late, his name appears on the lists next to the elected Kennedy. He immediately brought it to the attention of his bishop, and there the problems began: was priestly work compatible with politics? Man proposes and God disposes, our missionary thought. And to put on the brakes was to fail his faithful, who had elected him because they believed in him, and in practice, it was later demonstrated that he more than fulfilled his mission.

Even "Time" magazine echoed the news since it was the first time that a priest had been elected as a congressman, and the coincidence of Catholicism with President Kennedy raised more than one suspicion, and on top of that, it was a Spanish priest. The fact is that he did well, and served two legislatures, obtaining numerous advantages for his Alaskan district. And with his allowances as a politician, he built a new church in his main village, Alakanuk.

Father Llorente's life is full of an iron will, an indomitable but affable character, a broad smile, a willing desire to do his best for his fellow man. His homeland was always present in his prayers; his parents, whom he would never see again since they died along the way. His eight siblings, whom he would meet again (except for one, Amando, who would travel to Alaska), 29 years later on his first trip to Spain. The Leonese gastronomy, the "luche leonesa", the green landscape contrasted with the white Alaskan, his Castilian language which he would now only practice in his letters and his readings...

Segundo Llorente exemplified like few, or like many since there have been exemplary missionaries in the whole history of Christianity, a life dedicated to others, with ups and downs that he cured with hours of dialogue with his Lord. He almost died swallowed by the icy waters of a lake when his sled broke through the ice, or in two plane crashes, or lost in the fog in the arctic night, but, as he said, his guardian angel had a lot of work with him, working overtime every two hours.

And to endure temperatures of more than 65 degrees below zero, the terrible isolation, the lack of communication with the Eskimo, the extreme loneliness, and other weeds, Segundo Llorente had two important weapons: faith and excellent humor. His chronicles are always entertaining, amusing, illustrative, educational, enriching, informative, sensitive, and do not leave the reader untouched.

At 62 degrees below zero, the stove was the center where Segundo Llorente used to hide, on those nights, to meditate, pray, write letters, read good books, talk to Jesus Christ, play the accordion, or exercise his nostalgia. That stove that he cared for with pampering, with affection, with a devotion to light it and maintain it, because his well-being depended on it.

Missionary, hero par excellence, risking his life with his dog sled in the Alaskan steppe, passionate about his work and his mission, fond of his Eskimos, great catechist, and preacher, lover of the epistolary genre and of giving advice, wise in giving spiritual exercises, a shrewd politician who knew how to defend his natives as a deputy in the Congress of Alaska, strong and sober as a Carthusian, strong and fighter as a good Leonese, co-founder of the State of Alaska...

Segundo Llorente preached as he lived, and his example was the clearest message for those rudimentary Eskimos who saw in that man someone very special. They watched, with curiosity, how that missionary traveled by dog sled, by plane, on foot, to baptize their children, to marry others, or to give last rites to a dying person. He took the trouble to learn their language, and what he could hardly explain because it did not exist in those lands, he staged, theatricalized, put image and sound in his heavenly visions.

Everything was worthwhile to deliver the message of Christ in those inhospitable lands where the white man was synonymous with the slave master or the supplier of alcohol. The Alaskan mission bore much fruit, Segundo Llorente founded schools, nuns' colleges, new villages, churches, socialized labor with the Eskimos, catechized the children with his fantastic apocalyptic religious stories, gave much and received much.

I have spoken with numerous Jesuits, his companions in Alaska; with Mexican parishioners in the United States whom he married, baptized, or catechized; with seminarians and nuns who received his spiritual exercises or his catechetical courses; with his family and friends. And all of them, without exception, describe him as a holy man, in the best sense of the word, a great dialoguer, a perfect counselor, an excellent communicator, an unbeatable spiritual guide. Wherever he was, he became a legend.

And when one delves into the biography of this immense man, one discovers the many facets of his existence. He was not just a simple missionary. He was religiously committed to his work, not a conformist at all. He was a tireless fighter, a savior of souls. Ardent but dedicated, condescending but tenacious, tolerant but thoughtful. Missionary, mystic, adventurer, ethnologist, poet, yes poet, and a great communicator; in the life of this great man, the least that could be asked is to be able to spread his biography to know more and better a part of the history of America.

Author: Javier Nicolás, Source: Inclusion