What is the relevance of the SOTPE manifesto in the history of Mexican muralism?

SOTPE manifesto contains the general principles of Mexican muralism and also the social vocation that culture assumed as a result of the Mexican Revolution. Learn more about it.

In 1922, once he returned to Mexico from Europe, David Alfaro Siqueiros founded, with other artists, the Sindicato de Obreros Técnicos, Pintores y Escultores (SOTPE), Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, to defend the interests of those who worked in the decoration of public buildings and whose works sought to fulfill a didactic function.

Towards the end of 1923, Adolfo de la Huerta disowned the government of General Álvaro Obregón and was appointed provisional president by General Guadalupe Suárez. As a consequence of this event, power struggles in times of presidential succession were exacerbated.

Under these circumstances, on December 9 of that same year, SOTPE published a manifesto written by Siqueiros, who was its general secretary, and signed, along with him, by Diego Rivera as the first member, Xavier Guerrero as a second member, and Fermín Revueltas, José Clemente Orozco, Ramón Alva Guadarrama, Germán Cueto and Carlos Mérida (a little more than six months later, in the second half of June 1924, it would be published in number 7 of the newspaper El Machete, SOTPE's official organ).

Directed, with the exalted tone of the avant-garde manifestos and the post-revolutionary nationalist charge, to "the indigenous race humiliated for centuries, to the soldiers turned into executioners by the praetorians, to the workers and peasants scourged by the greed of the rich, to the intellectuals who do not envy the rich, and to the intellectuals who do not want to be involved in the struggle of the rich", to the intellectuals who are not debased by the bourgeoisie", this manifesto emphasized that the military uprising of Enrique Estrada and Guadalupe Sánchez (allies of Adolfo de la Huerta) clarified the social situation of the country and established, without ambiguity, the existence of two movements in conflict: on the one hand, the social revolution, represented by soldiers of the people, peasants and armed workers, and, on the other, the armed bourgeoisie, represented by soldiers of the people deceived or forced by political-military chiefs.

Further on, it assured that, since "the art of the people of Mexico is the greatest and healthiest spiritual manifestation in the world" [...] "because being popular it is collective" [...], "our fundamental objective lies in socializing artistic manifestations tending towards the absolute disappearance of bourgeois individualism".

It then repudiated easel painting and the art of the ultra-intellectual cenacle as aristocratic, exalted the manifestations of monumental art as being of public utility, and proclaimed that "being our social moment of transition between the annihilation of an aged order and the implantation of a new order, the creators of beauty must strive to create a new order, the creators of beauty must strive so that their work presents a clear aspect of ideological propaganda for the good of the people, making art, which is currently a manifestation of individualistic masturbation, a purpose of beauty for all, of education and combat".

Finally, the SOTPE manifesto called on Mexico's revolutionary intellectuals, "forgetting their proverbial sentimentality and laziness, to join us in the social and aesthetic-educational struggle we are carrying out," as well as all the peasants, workers, and revolutionary soldiers of Mexico to form a united front against the common enemy.

General principles of the SOTPE manifesto

What is the relevance of the SOTPE manifesto in the history of Mexican muralism? Alicia Azuela, the researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, answers: "Its importance is fundamental because it contains the general principles of this artistic movement, but also the social vocation that culture assumed as a result of the Mexican Revolution; that is, this manifesto gathers the spirit of the time that was forged in the Revolution, one of whose main postulates was to make a socially committed art and culture. Thus, it possesses an enormous capacity to synthesize the reflections of the political and cultural situation at that time and, at the same time, it marks one of the trends within mural production in Mexico."

Mexican muralism emerged as public art, monumental art, and art with didactic contents that were to educate or else exalt spiritual greatness. These principles are found in the first murals of the Antiguo Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo, and the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso (today San Ildefonso Museum), in the Historic Center of Mexico City.

"Later there was a clearer definition of this artistic movement, in which the historical circumstances themselves demanded that the content and function of art and the artist linked to concrete national problems and political militancy be specified or not. And this is the line that fed the manifesto and dictated the tendency within muralism, which is prototypical of what is understood as such," the university researcher points out.

Tools of social change

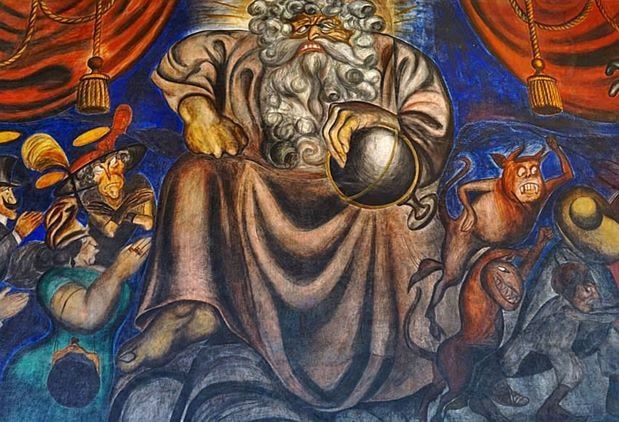

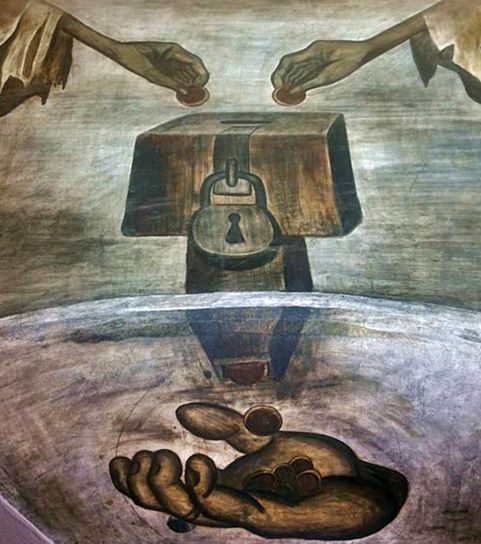

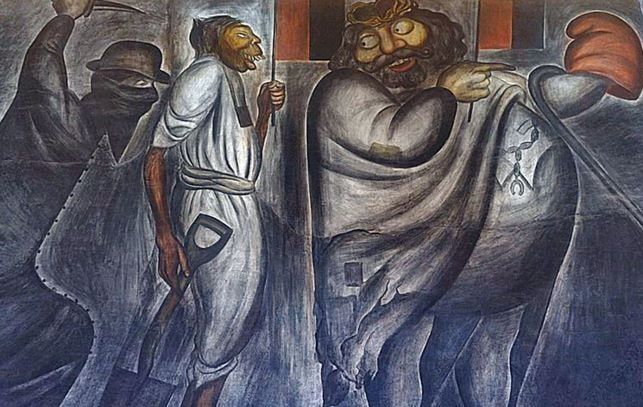

According to Azuela, the murals at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso that are directly related in time to the SOTPE manifesto are Siqueiros' Entierro del obrero sacrificado, which is a tribute to Felipe Carrillo Puerto, politician, journalist, revolutionary leader and governor of Yucatán between 1922 and 1924, assassinated in his state, revolutionary caudillo and governor of Yucatán between 1922 and 1924 assassinated in his state, and Orozco's La trinidad revolucionaria, El banquete de los ricos, Los aristócratas, Alcancía, Basura social, El acecho, La libertad, El juicio final and La ley y la justicia, since they were all painted between 1923 and 1924.

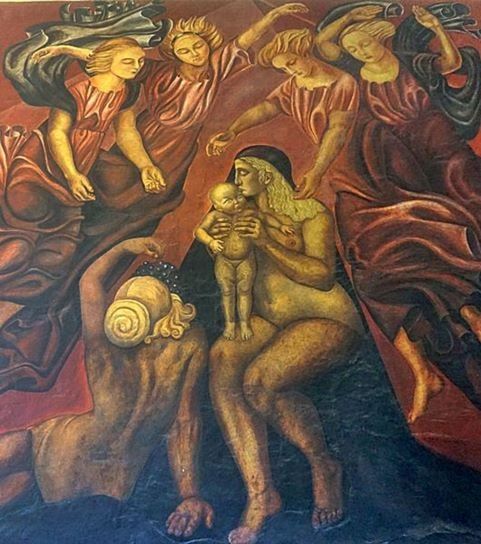

"Now, in the long term, in The Strike, The Trench and Destruction of the Old Order, painted in 1926, Orozco makes a reference, from a profound universalist point of view to concrete situations such as the defense of labor rights," she adds. The mural La creación (The Creation), was painted in 1922 by Rivera, that is, before the founding of SOTPE and the publication of the aforementioned manifesto.

"It is more associated with the first Vasconcello program, which asks artists to exercise a social function and address major themes that exalt ethics and spirituality. And here we are dealing with a work within the classical avant-gardism in vogue, with figures with an architectural, solid and essentialist structure inspired by both pre-Hispanic traditions and Western culture, in which the creation of the human being and the artist as a creator capable of changing history is embodied. In any case, if you want to find any relation between Rivera and the SOTPE manifesto, you have to look at Entrada a la mina and Salida de la mina, two of the 235 panels of Visión política del pueblo mexicano, the first mural with social content painted by Rivera between 1923 and 1928 at the Secretaría de Educación Pública", says the researcher.

On July 27, 1924, José Vasconcelos, who had put the walls of public buildings in the hands of plastic artists to paint their murals and was convinced that art and culture were, per se, tools that helped to achieve social change, but should not be contaminated with political issues, resigned from his position as Secretary of Public Education. He was succeeded by Bernardo Gastélum, who, faced with the call for knowledge and the struggle for social rights advocated by the muralists, soon cut their budget and left them without work.

"And after a few months, with Plutarco Elías Calles in power, freedom of expression was conspicuous by its absence, so the fate of SOTPE was its dissolution. The matter is fascinating because the manifesto of this union can be studied and understood as a product of a very specific historical moment and also because of its links with the Mexican artistic movement that has achieved greater international transcendence," Azuela concludes.