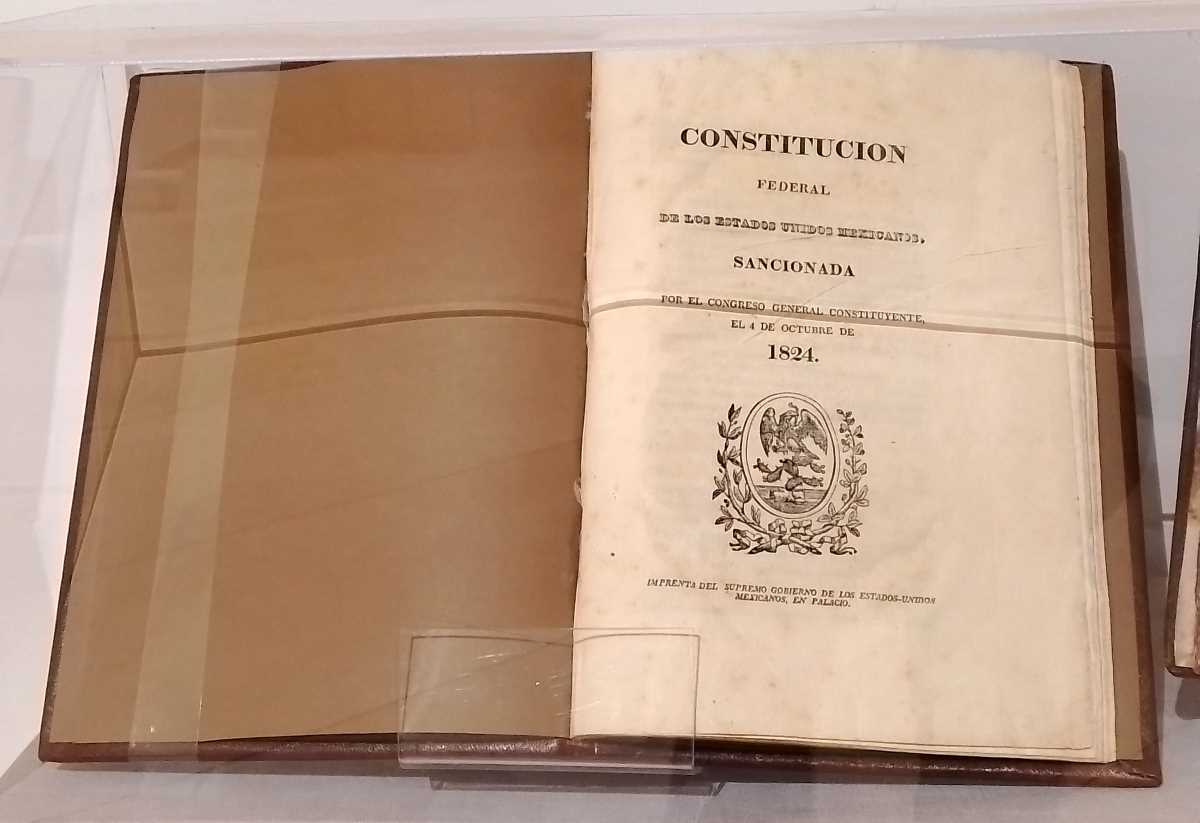

The 1824 Constitution Two Centuries Later

The bicentennial of Mexico's 1824 Constitution offers an opportunity to reflect on its enduring legacy. Legal scholars and political figures emphasized the document's continued relevance in shaping the nation's political and social landscape.

The 1824 Constitution of Mexico. A document so venerable, so deeply entwined with the very roots of the nation’s identity, that commemorating its bicentennial feels less like a trip down memory lane and more like a poignant reminder that history never truly dies. And why would it? This country, much like a well-aged tequila, is distilled from the complex flavours of its past – some parts smooth, some sharp, and others downright combustible. Yet, the lessons remain there for those willing to take a sip.

On this momentous occasion, Sonia Venegas Álvarez, director of the UNAM Faculty of Law, spoke at length about the legacy of the 1824 Constitution. She didn’t simply drone on in a lecture hall – no, she painted it as a “radiant beacon,” an inaugural milestone that set the course for Mexico's independent political existence.