The archaeological site La Quemada was abandoned gradually, not by fire or invasion

Although it was believed that the place had been abandoned by a large fire or an invasion, the experts assured that it was gradually evicted.

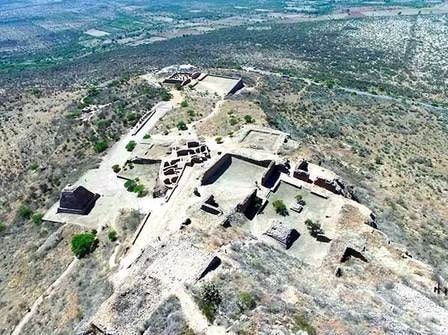

The archaeological site La Quemada, one of the most mysterious in Mexico, located in the center of the state of Zacatecas, was gradually abandoned, not because of fire as is thought, experts from the National Autonomous University of Mexico said.

Avto Goguitchaichvili, head of the National Archeomagnetic Service (SAN) of the Geophysics Institute (IGEF), Morelia campus of the UNAM, said that La Quemada is an important place for the history of Mexico since it has been linked to Chicomóztoc, a place where the Mexicas passed on their trip to Anahuac, so it could be a place of origin or rest for Nahuas, Teotihuacan, Toltec and Tarascan.

According to his research, there was a fire at the top of the hill, around the Plaza de los Sacrificios, between the years 854 and 968 of our (9th and 10th centuries), but the area was not abandoned until the 1018s and 1163 when another fire affected the lower part. The place where the second fire was recorded was the Hall of Columns, a ritual site, so the fire could be provoked as a ceremony to close the site.

"If it had been a war problem, the burials would have already been found, but there are no human remains in abundance, and it was not a ritual issue either, we believe that the second fire was a ceremony to close the site."

Although it was believed that the place had been abandoned by a large fire or an invasion, the experts assured that it was gradually evicted, possibly due to social decomposition.

"As everything was burned, we initially thought, like archaeologists, that there was a fire and the city was evicted, but after the investigations, our most important finding is that the abandonment was gradual."

Through several studies, the university students found that it is a settlement with 700 years of occupation, developed from 400 to 1100 AD. and they affirmed that it was not a place of passage, ceremonial center, or military fortress, as it was believed, but of a ruling settlement of a valley, known as the culture of the Malpaso Valley. This settlement maintained contact with neighboring groups such as the Chalchihuites culture, inhabitants of the Juchipila Canyon and Tlaltenango, within the current state of Zacatecas; as well as El Tunal Grande, in San Luis Potosí; the Altos de Jalisco and the Guanajuato Bajío.

To determine when the area was unoccupied, a series of 32 pieces obtained from the Hall of Columns, the Plaza de los Sacrificios, and a corridor, located at the top of the hill, were subjected to archaeomagnetic analysis, to determine they're magnetic and select the most promising They used archaeomagnetic dating, since, unlike radiocarbon dating, the archaeomagnetic dating indicates the cooling moment of the magnetic materials, so that the object is dated directly. This method is based on the study of pieces burned during heating at high temperatures or fire, such as floors or ceramics containing small amounts of ferromagnetic minerals, among the most common: magnetite or hematite.

It is the first time in the history of the National Archeomagnetic Service that there is greater precision in the events that occurred, considering the traditional methods of dating. The SAN team will continue collaborating with the INAH to study the vestiges of the area and to date, with more precision, the secrets still kept in the western region of the country.