What was the Beat Generation and why it was important?

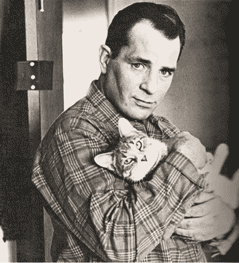

The Beat Generation is a literary movement that emerged from the vision of a group of writer friends who met in late 1944 at the West End Bar in Manhattan, New York: among them were Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and John Clellon Holmes.

Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), William S. Burroughs (1914-1997), Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1919-2021), Gregory Corso (1930-2001), Gary Snyder (b. 1930) and perhaps others are the eponyms of the Beat Generation. The literary value of their works is still debated, although it is generally accepted that they introduced new themes, styles, and narrative techniques into the American novel and poetry.

However, it is less doubtful that their works and the legends woven around their lives would powerfully influence the youth culture of the next decades, especially in their exploration of the US underclass, drug use, sexual freedom, and a certain interest in "exotic" cultures. In this last case, Mexico represented not only a real territory in which the beats took refuge from the rejection and persecution they were subjected to in the U.S. but also the possibility of accessing a place where they could realize their utopia. Kerouac expressed it this way, telling in his famous novel On the Road his first arrival in Mexico:

Behind us was all of America and all that Dean and I had previously known of life, and of life on the roads. We had found, at last, the magic land at the end of the road, and we had never dreamed the extent of that magic.

The Beat Generation

With the Second World War, the world changed in a way never seen before. The technological development achieved made it possible for human beings to expand their reach and radically transform their environment, but the horrors unleashed in the war showed that this same capacity also entailed the threat of destroying life on the planet. In the United States, a group of young writers, artists, and intellectuals sought to question the values and foundations of postwar Western capitalist society. They became known as the beat generation.

The barbarity and atrocities of the Nazis were responded to in no less deadly and cruel ways by the Allied armies: the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with American atomic bombs, the "strategic" bombings of the British air force on the civilian population of Germany or the systematic rape of German women by Soviet soldiers in Berlin and other places left no doubt about it. Europe and Asia were devastated, but in the United States of America (USA), the majority of the population lived an optimistic and euphoric moment, since the horrors and disasters of the war had not been suffered in its territory. In fact, that nation was emerging from the war as the world's hegemonic power. As a result of its political and economic dominance, its socio-cultural models would soon spread to other countries.

However, not all U.S. inhabitants enjoyed the post-war bonanza and optimism equally. The black population -which was increasing daily in the big cities due to migration from the countryside to the industrial and commercial centers- continued to be discriminated against and crowded into the ghettos of the suburbs. Hispanic Americans -mostly of Mexican descent-, whether residents or temporary migrants, almost all occupied low positions on the socio-economic ladder (many working as laborers and day laborers on ranches and agricultural plantations in the western and southwestern states). People of Asian origin were also kept apart in their neighborhoods (the famous Chinatowns). Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians were subjected to the system -legitimized by laws and customs- of racial segregation. Although perhaps somewhat more accepted than those others, the descendants of white Europeans who had recently migrated to the U.S. were not recognized as equals by the dominant wasp population, especially when they were people who, although white, differed in religion and ethnic or national background from the dominant wasps.

The ideology of the North American wasp privileged the attainment of an ideal social status based on the preeminence of the individual who managed to obtain high levels of wealth. In this socio-cultural context, women, even if they were also wasp, occupied a position subject to the designs of a male individual on whom they generally depended (father, brother or husband, boss or employer, etc.). And if anything, the difference with the wasp had nothing to do with race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or even age (since young men were also excluded from decision-making power), but rather with alternative preferences (homosexuality, non-Christian religious beliefs, drug use, strong interest in other cultures or, simply, different musical tastes, for example), the strong conviction of the social norms in vogue at the time was that reality is one and indisputable and that, therefore, any otherness or dissidence should be understood as abnormality, madness or degeneracy - and treated as health problems, thus implying other forms of segregation - or, even worse, be considered as attacks against society (and, consequently, be punished).

To make matters worse, in the first part of the 1950s an anti-communist mass hysteria was unleashed in the USA, the most outstanding manifestation of which was the so-called McCarthyism. This term refers to the persecution unleashed against alleged communist militants or sympathizers and derives from the name of its main leader, Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy. When, between 1949 and 1950, the USSR exploded its first atomic bomb, Mao Tse Tung's Red Army seized power in China and the Korean War began, American sectors frightened by the communist advance supported McCarthy's initiative to create the Senate Committee on Un-American Activities, which dedicated itself to carrying out a "witch hunt" in the country. The accusations of subversion or treason, which were initially leveled against government administration officials, soon spread to academics, trade unionists, businessmen and, most notoriously, actors, directors, screenwriters, and other people in the world of the United States, (The McCarthyites sought to gain publicity for their cause by extending their accusations to this popular sector, but, although they succeeded, the matter proved to be a two-edged sword, since the reaction against the abuses and the unfounded accusations of the McCarthy Committee largely stemmed from there). Those accused of activities deemed un-American included not only supporters - real or invented - of communism, but also homosexuals, liberals, or anyone else whose public positions or private behavior could be considered contrary to what wasp conservatism held to be appropriate for American society. Many people were thus subjected to legal proceedings, lost their jobs, or were barred from employment.

Against this backdrop of social and political intolerance, gender and class inequality, and racial and cultural segregation, a group of writers, poets, and editorial writers confronted the Wasp vision of human progress. Composed basically of white, middle-class young people with a certain level of education, this group began to form in the aftermath of World War II, but it was not until more than a decade later (in the late fifties and early sixties) that their works would reach wide circulation. In reality, the beat movement never had a well-defined political character, since its objections to conservatism and the hardening of repressive state policies manifested more a desire to escape the restrictions that were imposed and the consumerism and conformism that permeated the upper and middle classes of North America, rather than coherent proposals for a radical socio-political transformation.

A magical land?

Although it was actually laying a firm foundation for the development of capitalism in Mexico, the Revolution of 1910-1920 was viewed sympathetically by liberals, leftists, and critical thinkers in the U.S. and Britain, including several writers. The radical revolutionaries and Obregonist propaganda promised the redemption of the poor classes, worker collectivism, and the distribution of land among the peasantry, but many of the reforms remained in words and not in deeds, while the distribution of wealth (which after 10 years of the civil war was little) was more among the former landowners and the triumphant leaders of the revolution, instead of reaching the majority of the common people. However, the climate of optimism about the forging of a new nation was nevertheless driven by the government sector in charge of educational and cultural aspects. Mexico's "cultural renaissance" achieved worldwide fame through the paintings of Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, and other artists, who in their murals and other works proposed the redemption of the indigenous in the country's history and extolled the links between native cultures and their natural surroundings.

During the first half of the twentieth century (and perhaps a little later), a plethora of English-language writers published works recounting their experiences in Mexico.

Carleton Beals (1873-1979), B. Traven (Traven Torsvan, 1890-1969), Katherine Anne Porter (1890-1980), David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930), Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), Malcolm Lowry (1909-1957), Graham Greene (1904-1991), Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), John Steinbeck (1902-1968) and Tennessee Williams (1911-1983), among others, are among the authors (and authors, of course) who, in addition to publishing essays and other realist writings about our country, distinguished themselves perhaps most notably for their works of fiction (novels and short stories) or their poems, in which they captured their perception of this land and its inhabitants. To a greater or lesser extent, each of them presented in their novels visions of places and people in which the extremes were confusingly close.

For example, the great mass of the rural population-still at that time composed of a significant proportion of speakers of indigenous languages-was conceived, through the characters developed in the novels, either as a redeeming influence that in its supposed primitivism was close to the simplicity of the peasant bound to nature or as an uncontrollable force that at times cried out for vengeance for the secular wrongs done to their race and their ancient gods.

But whatever the approach adopted by these writers, their portraits, allegories, and images of Mexico, they constructed a paradigm in which, for the foreign writer, life in this country made possible, thanks to its forceful contrasts, not only the distance from the rigidity and demands of Anglo-Saxon morality and the disenchantment caused by industrialism and consumerism that prevailed in their countries of origin but also allowed them to locate a place where, by magic, tragedy could be transformed into joy, fear of the future into an evocation of the past and perhaps, death into life. Perhaps it was the British Malcolm Lowry who summed up very clearly the sentimental ambivalence that assailed this type of artist:

The person who falls in love with Mexico falls in love with an entity full of color, proud and present ... but enters, in the deepest sense, into a mystery ... The sense of its past, of the pain of death; these are the intrinsic factors of Mexico. However, Mexicans are the most joyful people, who turn every possible occasion, even All Souls' Day, into a fiesta. Mexicans laugh at death; this does not mean that they do not take it seriously. It is perhaps only by possessing a sense of life as tragic as theirs that joy and rejoicing find their place; it is an attitude that testifies to the dignity of man. Death overcome by resurrection is tragic and comic at the same time. On many planes this is true ... It is undoubtedly true that some people are drawn to Mexico as to the hidden life of the man himself; they wonder if they might not even discover themselves there.

The search for that magical world - and for their own personal destiny - continued among the writers of the second part of the twentieth century, and those of the beat generation were no strangers to this phenomenon. But when Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsberg, and their friends arrived in Mexico from 1950 onwards, the country was rapidly transforming, integrating itself into global economic processes; it was thus that Jack Kerouac had his first experiences with the Mexican not in our country, but in his own.

A fellaheen world?

Mexico had declared war on Germany, Italy, and Japan in 1942. Its contribution to the Allied triumph in the military aspect had been, although honorable, relatively small. The 201st Squadron of the Mexican Air Force fought on the Pacific front with 300 men (including pilots, guards, and service personnel) of which it lost nine. Moreover, during the war, an undetermined number of crew members of several merchant ships sunk by German submarines in the Atlantic died (perhaps less than a hundred). But Mexico's contribution to the Allied victory was more decisive in another area.

Between 1942 and 1945, thousands of Mexican workers, the so-called braceros, legally entered the U.S. to replace U.S. workers enlisted in the army and sent to fight in Africa, Europe, and Asia. By 1945, there were about 45,000 Mexican braceros working in agricultural production units and about 75,000 in the railroad system. The importation of braceros for railroad work formally ended shortly after the end of the war, but the Mexican Farm Labor Program continued until 1964. In those 20-plus years, nearly 4.5 million Mexicans worked as braceros, making Mexican immigration to the U.S. a common practice that laid important economic and political foundations for current relations between the two countries. In the cultural sphere, the braceros (and later the illegal immigrants who succeeded them) signified the renewal of a Mexican presence, very noticeable especially in the western and southwestern states of the United States. And that presence left its mark in the imaginary of the beat, especially in Jack Kerouac, who a few years before visiting Mexico, had a relationship with a Mexican woman (called Terry in On the Road) with whom he worked picking cotton in the fields of California.

We bent down and started working. It was beautiful. There were [tents] scattered about the field, and past them, the brown cotton fields stretched as far as the eye could see ... It was much better than washing dishes on South Main Street ... Also in the field was a couple of very old Negroes. They picked cotton with the same blessed patience that their grandfathers did in Alabama before the Civil War ... I made about a dollar and a half a day. It was just enough to go shopping for groceries on the bicycle in the afternoon. The days went by. I completely forgot about the East [the east coast of the U.S. where he lived] and Dean and Carlo [his friends] and the damn road [the road]. Johnny [Terry's little boy] and I played all the time; he liked me to throw him in the air by dropping him on top of the bed. Terry would mend clothes. I was a man of the earth, just as I had dreamed I would be.

In Kerouac's work, much more than in those of the other beat writers, Mexico is identified as a world where the fellaheen are found, the simple and hardworking people who in Kerouac's imagination are assimilated to the indigenous people and the poor peasants. Kerouac speaks of them in this way when he enters Mexico:

... I am seeing the inside of those houses as we pass by ... you look inside and you see straw cradles and very brown children sleeping and stirring about to wake up with their thoughts coming out of the empty mind of the sleep, recovering their own being, and the mothers preparing breakfast in iron pots ... and look at those blinds they have on the windows and the old men, those old men so serene and without any concern. Here nobody distrusts, nobody is suspicious. Everyone is calm, everyone looks you straight in the eye and says nothing, they just look with their dark eyes, and in those looks, there are soft, quiet human qualities, but they are always there. Look at all those stories we've read about Mexico and the sleepy Mexican and all that crap about them being greasy and dirty and all that when here people are honest, they're nice, they don't bother.

For Kerouac, these Mexicans were in some ways similar to people from the underclass of the American society of his time: the underclass, the lumpen-proletariat in the affluent American nation, and the African-Americans. On the other hand, the amalgam of Catholicism and Buddhism that characterized Kerouac's religious thought played a role in his interest in the cultures he considered fellaheen, for according to his conceptions these cultures embodied authentic suffering, and through it, could free themselves from the corruption of modern society and the influence of linear time. Like the Arab fellaheen, for Kerouac, the Mexican natives and peasants were a people without history, or rather, outside of history, since they lived in the immediacy of the present. By dispensing with the pain caused by the passage of time, these fellaheen had no need to construct false beliefs and were, therefore, closer to nirvana. For the writer, their role in the history of human becoming remained as immovable as that of the rocks.

By Andrés Ortiz Garay, Correodelmaestro.com