Rise and decline of a historiographical theme: What is the history of mentalities?

The notion of mentalities—used more commonly in the plural than in the singular—acquired significant diffusion and importance within the Western academic world throughout the seventies and eighties of the 20th century.

If my successors prefer to study mentalities while forgetting economic life, so much the worse for them! For my part, I would not study mentalities without considering all the rest at the same time... because there is no autonomous history of mentalities, they are always linked to the whole.

Fernand Braudel

Summary

The concept of mentalities—used more frequently in the plural than in the singular—acquired great diffusion and relevance within the Western academic world during the seventies and eighties of the 20th century. This international diffusion and projection were associated with the fact that it was at this juncture, from 1968 to 1989, that the French historiography produced by the famous Annales current also spread globally. Jacques Le Goff's History of Mentalities is an ambiguous and very loose definition of the term "mentality. This ambiguity and lack of definition make it more difficult both to understand and to discuss its possible contributions, but also its main limits and inadequacies. This is a typical and exclusive product of the great social and cultural effects provoked by the cultural revolution symbolized by the historic date of 1968.

This is because this genre addressed, from a historical perspective, precisely those realities and dimensions of the social fabric that the '68 movement had placed at the center of its contestation and its challenges and that, after that date, would begin to change rapidly. Thus, given expression, within the discourse and work of historians, to the social and cultural concerns of the historical conjuncture of 1968–1989, this history of mentality is fully installed within the concerns of its time, achieving at the same time the conquest of a vast diffusion by the media and an equally wide circulation within the historiographic and social science fields all over the planet. The history of mentalities is often seen as a history of what it denies and criticizes, as opposed to what it tries to overcome. For in every case, the approach that needs to be changed is that of the classical history of ideas, which has always focused on re-creating only the big ideas or the big thinkers' systematic views of the world.

Mentality: an ambiguous and undefined concept

The concept of mentalities - used more frequently in the plural than in the singular - acquired great diffusion and relevance within the Western academic world during the seventies and eighties of the 20th century. This international diffusion and projection were associated with the fact that it was at this same juncture, from 1968 to 1989, that the French historiography produced by the famous Annales current also spread globally, to become present in the most diverse fields of historiography and social sciences throughout the world.

And since the third generation of this misnamed "school" of Annales claimed, above all, the project and the exploration of a "history of mentalities", then its affirmation and wide diffusion in Europe and the world -which unfolded precisely during the 1970s and 1980s- will run parallel to the popularization and also extensive recovery of this ambiguous term of mentalities -to the point of creating neologisms, both in German (mentalitáts) and English (mentalities), to designate this term launched to fame by French historians after the enormous cultural revolution of 1968, even to the point of creating neologisms, both in German (mentalitáts) and in English (mentalities), to designate this term launched to fame by French historians after the enormous cultural revolution of 1968.

However, despite this wide diffusion and popularity, to this day there is no precise and universally accepted single concept of the term "mentality" and, consequently, there is no clear and univocal definition of what this famous "history of mentalities" encompasses and implies. Because this "mentality", rather than designating a well-defined analytical concept referring to a precise set of elements or realities that have been rigorously theorized and delimited, has functioned more as a purely descriptive and connotative term that alludes to a vast and imprecise problematic field, which includes, according to the different authors, everything from the behavior of the individual to the behavior of the individual, according to different authors, from everyday behaviors and gestures to an ungraspable "collective unconscious", including emotions, popular beliefs, forms of consciousness, epistemes underlying discursive construction, ideological structures or social imaginaries, among many other possible elements.

A disparate and heterogeneous set of dimensions that perhaps explains the fact that Jacques Le Goff himself -one of the important French promoters of this history of mentalities- has unequivocally confessed, when trying to explain this history of mentalities, that it was an ambiguous history. And it is a fact that almost all critics of this history of mentalities underline precisely this ambiguity and lack of definition, which makes it more difficult both to understand and to discuss its possible contributions, but also its main limits and inadequacies. This, moreover, obliges each new author who ventures into this same history of mentalities to redefine and specify its supposed contents.

An ambiguous and very loose definition of the term mentality has allowed its defenders to postulate the false idea that such a history of mentalities would go back at least to the beginning of this century, including among its antecedents authors and works as different as those of Lucien Levy-Bruhl, Johan Huizinga, Marc Bloch, Lucien Febvre or Georges Lefebvre, among so many others. However, by carefully approaching and attentively comparing Levy-Bruhl's book, The Primitive Mentality, or Huizinga's The Autumn of the Middle Ages, with Marc Bloch's The Thaumaturgical Kings or Georges Lefebvre's The Great Panic or Lucien Febvre's The Problem of Religious Unbelief in the 16th Century-The Religion of Rabelais, it is easy to see that it is a matter of the same thing, it is easy to realize that these are very different intellectual approaches and models of analysis, and also quite different from the equally diverse models of "history of mentalities" practiced in the sixties, seventies and eighties of the twentieth century.

There is not then, contrary to a widely held but erroneous opinion, a true affiliation, and continuity between the works of Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre -which already, among themselves, are very different-, that is, between the authors of the first generation of the Annales and the works on mentalities of that third generation of Annnalists after the cultural rupture of 1968. This, for example, is already evident in the letter that Marc Bloch sent to Lucien Febvre on May 8, 1942, a letter in which he qualifies the term mentality as "a mediocre term" that "lends itself to some misunderstandings".

Therefore, this term of mentality and this history of mentalities are, rather than the prolongation of a previous and venerable tradition that dates back to the twenties and thirties of this century, a typical and exclusive product of the great social and cultural effects provoked by the enormous cultural revolution symbolized in the historic date of 1968.

Because it is clear that this unusual popularity and diffusion, both of the term and of the genre of mentalities itself - in France as well as abroad - is due above all to the fact that this genre addressed, from a historical perspective, precisely those realities and dimensions of the social fabric that the '68 movement had placed at the center of its contestation and its challenges and that, after that date, would begin to change rapidly.

And then, the years in which all the mechanisms of cultural reproduction of modern societies were radically transformed are also the years in which those histories of the family, histories of private life, histories of the attitude to death, to fear, children and women in the Ancien Régime, which constitute so many other examples of that history of mentalities then so much in vogue, were written and profusely disseminated.

Thus given expression, within the discourse and work of historians, to the social and cultural concerns of the historical conjuncture of 1968-1989, this history of mentality is fully installed within the concerns of its time, achieving at the same time the conquest of a vast diffusion by the media and an equally wide circulation within the historiographic and social science fields all over the planet.

History of mentalities and history of ideas

Since this history of mentalities, like the term mentality itself, has been given so many different meanings by the different authors who have dealt with it, it is easier to define it by what it denies and criticizes, as opposed to what it tries to overcome than in a positive and precise way.

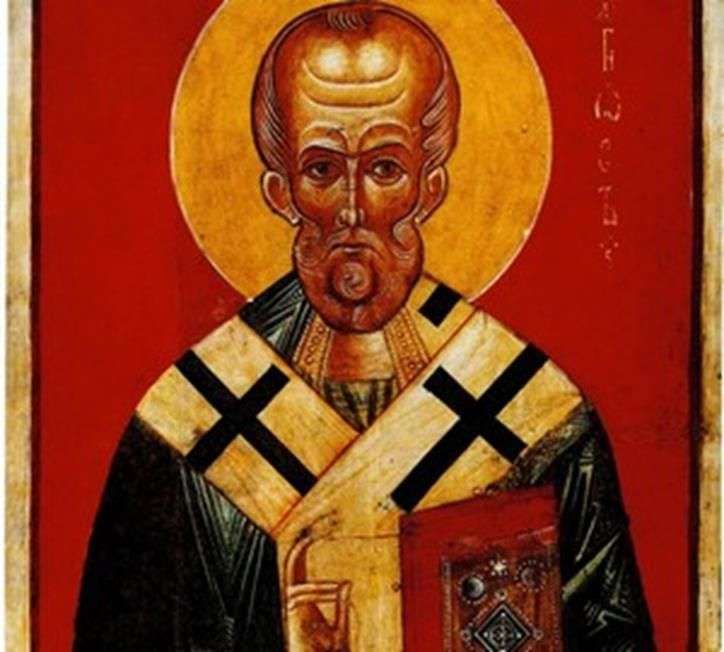

Thus, most of the advocates and practitioners of this history of mentalities repeat the line of radically opposing this history of mentalities to the old, traditional, and already anachronistic history of ideas. For in all cases, the approach to be overcome is precisely that of the classical history of ideas, which has always concentrated on reconstructing only the great systems of thought or the systematic conceptions of the world of the great thinkers, paying attention only to the work of notable scientists, great writers or artists, or renowned "intellectuals", or even, going a little further, to the always elitist literary currents, political trends, intellectual currents or great artistic movements of a given epoch.

Contrary to this predilection of the traditional history of ideas for the conceptions of a single individual or a small group of individuals, the history of mentalities will claim instead the study of the more collective dimensions of these same problems, addressing rather the popular beliefs of a given society, or the universal worldviews of a certain century, or the socially diffused views on this or that scientific problem, or the cultural or artistic sensibility of the masses in a specific period.

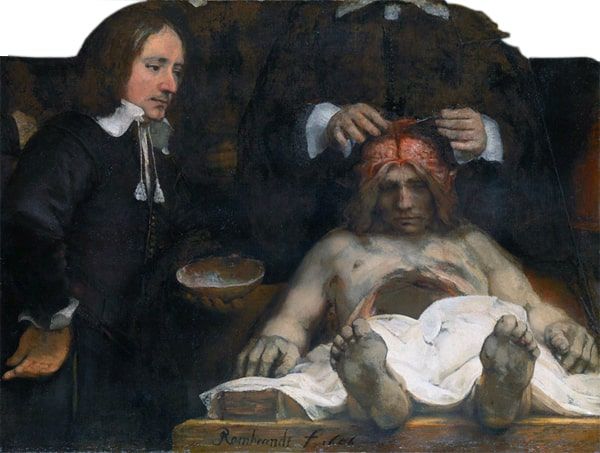

Changing then its center of interest and its general approach, the history of mentalities will study not the work of Voltaire but the cultural conceptions of 17th century France, and not the contributions of Galileo Galilei but rather the change of mentalities concerning scientific perceptions in the final period of the Renaissance. And also, rather than analyzing the contributions and failures of Bakunin and the anarchism of the 19th century, this history will be devoted to the study of the working-class sensibilities of Italy, France, Switzerland, and Spain in these same times.

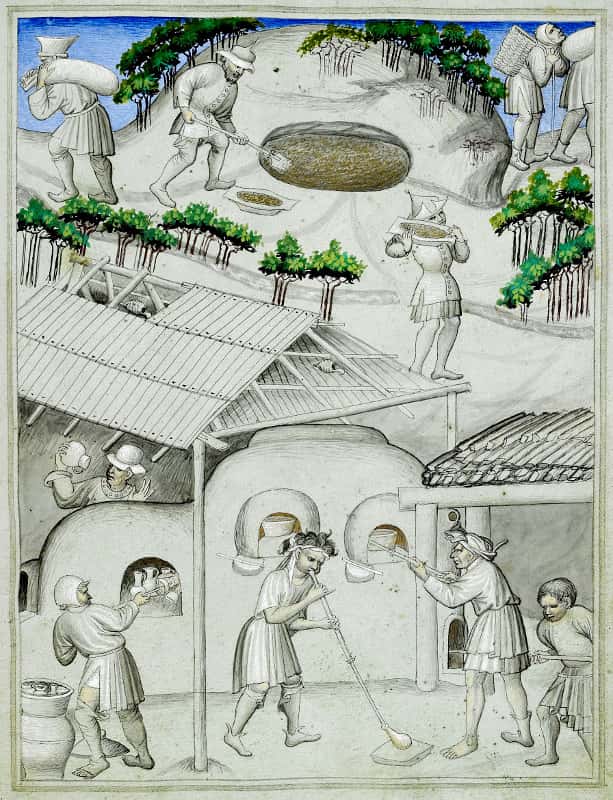

On the other hand, and also in contrast to this nineteenth-century history of ideas, always concerned with the conscious, coherent, and well-ordered constructions of the aforementioned systems of thought, the history of mentalities will also attempt to recover the unconscious, unspoken, unsystematically organized dimensions of the culture and beliefs of a society. That is to say that, once again changing its center of gravity, the history of mentalities will seek its sources not in the works of the great thinkers or the great cultured texts, but in the simplest and most everyday texts and even in the gestures, iconography, painting and the most trivial and popular forms of representation of society.

Passing then from individuals and elites to large social groups and collectivities, and from the systematic conscious level to the unconscious and unorganized levels of culture and popular beliefs, this history of mentalities attempts to go beyond the limited, punctual, and already anachronistic history of ideas, whose main models were elaborated in the nineteenth century and remained unchanged until that juncture of the years 1968-1989 that we have already evoked above.

Mentalities under the prism of critique

Representing a step forward concerning the old history of ideas, the French history of mentalities, welcomed and projected by the third Annales, has nevertheless given rise, almost from its very origin, to a whole series of recurrent and quite pertinent criticisms.

First of all, and repeatedly, a criticism of the indefinite, imprecise, and ambiguous nature of the very concept of mentalities. A concept that, presenting a more connotative than rigorous character and articulated in theoretical terms, has been defined in very different ways by each of the various authors who have tried to present it.

And so, acquiring a sense of designation of a certain not very precise genre of problems rather than a clearly established and strictly hierarchical and structured status, this term of mentalities -which Jacques Le Goff himself explicitly characterizes as "ambiguous"- has served as a sort of general umbrella for the shelter of research of very different relevance and very heterogeneous depth.

Because it is enough to carefully compare the definitions -clearly different and sometimes even alternative and partially exclusive- given by authors such as Robert Mandrou, Georges Duby, Michel Vovelle, Philippe Aries, or Jacques Le Goff, to realize that it is a term that never achieved a strong theoretical elaboration and construction.

Its invention responded more to the desire and the need to designate or connote in some way, albeit provisionally, this new space of problems that the traditional history of ideas had ignored, and which the effects of the 1968 cultural revolution brought up to date, urging the discourses of the social sciences to recognize and explain in greater detail.

This explains the fact that at a given moment almost all research on somewhat exotic or strange topics of history has been qualified as the history of mentalities, thus including under this heading problem that was essentially alien to those mentalities and that corresponded more precisely to specific forms of anthropological history or studies of the history of daily life, or to research on the linguistic, folkloric or artistic history, among others.

And also the fact that almost immediately the discussion was opened concerning the links, articulations, overlaps, or specific nexuses of these mentalities with other concepts coming sometimes from strong theoretical traditions and much more elaborated and problematized, such as the concepts of ideology, forms of consciousness, culture, imaginary or unconscious.

A second criticism -also recurrent among analysts of this problem- of this weak concept of mentalities, states that due to this same lack of systematization and greater rigor in its elaboration, it was a concept that left in suspense the relationship that such mentalities had -whatever the content assigned to them- with the broader social totality as a whole.

For, example, the concept of ideology, which always refers to very precise relations with classes and social groups, economic realities, and with social conflicts at the very level of culture, the concept of mentalities, in its total ambiguity and indeterminacy, left this problem completely silent, allowing both positions that claimed the absolute autonomy and explanatory self-sufficiency of these realities of the "mental", and positions that, on the contrary, tried to establish and reconstruct, creatively and interestingly, the different and complex bridges of the relation of these mentalities with the social whole.

And just as each author who dealt with these mentalities felt obliged to contribute his definition of them, so each specialist who has ventured into these territories has resolved in different ways this equally undefined point of their connection with the other levels or dimensions of the complex social fabric. This only confirms the fact that the history of mentalities is neither a theoretical paradigm nor a methodological perspective, but only a new problematic field that can be approached from very different perspectives, approaches, paradigms, or intellectual approaches.

Finally, the third criticism against these mentalities is that which refers to their alleged "transclassist" or universal character. For if we affirm, as Jacques Le Goff does, that mentality is that which "Napoleon shares with the humblest of his soldiers or Christopher Columbus with the last of his sailors," what we do is to evacuate the fundamental and inescapable role of class conflict in the cultural sphere and with it the also essential distinction between the culture of the dominant classes and popular culture. Two essential parameters of the analysis of cultural phenomena, which, when ignored, inevitably negatively bias any possible analysis of these heterogeneous realities included in the term mentalities.

These three criticisms, constantly repeated in the face of this French history of mentalities, have not, however, prevented its very wide diffusion both in France and abroad during the whole of the 1968-1989 period. This testifies as we have already pointed out, to the depth of the changes unleashed by the cultural revolution of 1968, and to the urgent need for French society, as well as other societies, to assimilate and intellectually process these changes.

Towards a typology of the different models for the study of mentalities

History of mentalities, which will then flourish abundantly in France in the 1970s and 1980s, to become the most original and characteristic contribution of these third Annales. But as we have already noted, it will not have a homogeneous and well-defined character, but on the contrary, it will unfold through different strands or models very different from each other.

And it is curious to note that neither scholars of the Annales current in general, nor those who concentrate on analyzing this third generation of Annalesists and this history of mentalities in particular, have so far attempted to construct a general typology of the different models of the history of mentalities that flourished within French historiography in the immediate post-1968 period.

A general typology that would undoubtedly merit a more detailed investigation and which, when it becomes concrete, would certainly have to point out the differences between the following "models" of approach to these mentalities:

1.

The model of an autonomous, self-sufficient, and almost idealistic history of mentalities. This model is exemplified in the work of Philippe Aries. Man in the face of death, the evolution and transformations of the different attitudes of men toward the act of dying are referred to, finally, as the changes of an ethereal and undefined "collective unconscious".

A model that completely abstracts from the general social context, and from the real and material changes of the societies that have elaborated and developed these diverse ways of dying, to try to explain them only through exclusively psychological factors, such as the progress of self-awareness, the rejection of savage nature, or the beliefs in life after death and in evil.

A model supported by an enormous and sometimes very interesting factual erudition but completely limited by this perspective that considers mentalities as a self-explanatory phenomenon and independent of other spheres or processes of the social totality.

2.

A second model of history, or archeology and genealogy of discursive structures and the foundations underlying the very construction of discourses. A completely original model, associated with certain works by Michel Foucault such as The History of Madness in the Classical Period, Words and Things or Watch and Punish, which, while explicitly rejecting the concept of mentalities, and also the objective of reconstructing a problem from a traditional linear and chronological historical sequence, will nevertheless prolong to some extent the type of history of mentalities proposed by Lucien Febvre in his book on The Problem of Religious Unbelief in the 16th Century - The Religion of Rabelais.

For it is more than evident the closeness between the Febvrian "mental tools" and the Foucauldian "episteme", both used to discern what is possible and what is impossible to think and conceive in any given epoch. A model then of archeology and genealogy of discourses, supported by a complex synthesis of philosophy, linguistics, and the history of sciences that will be applauded and revered by the third Annales, but that outside of Michel Foucault's work will have almost no significant imitators or followers.

3.

A third model of history that we could call neo-positivist or purely descriptive of mentalities. That is to say, a variant that, based on the abandonment of the perspectives of global history and the strong methodological debate that had characterized the Annales from 1929 to 1968, has cultivated almost purely descriptive and testimonial works on the history of the family, the history of the body, the history of a medieval peasant revolt, the history of death, etc., which only reproduces for us a kind of history of the past, which only reproduce a sort of dissection or X-ray of such an attitude, institution, movement, belief or phenomenon of mentality in a certain epoch or society, but without ever attempting to elaborate general models or articulated explanations of a longer-term nature of the subjects they deal with.

A model of historicization of mentalities that is a resurrection of the old and traditional positivist history, purely narrative and descriptive, and that in this case is also applied to this problematic field of mentalities. A field that, as is clear in this version or model, accepts any possible approach or perspective of analysis, and even quite traditional perspectives.

A model that has also been present in some of the results of those third Annales, to spread later with a certain amplitude in France and even more in Spanish historiography after Franco's death and in Latin American historiography over the last decades.

4.

A fourth approach would be that of a sociological or socio-economic history of mentalities exemplified in the works of Georges Duby, for example in his book on The Three Orders or the Imaginary of Feudalism. An approach that, in trying more seriously to imbricate these mentalities with the social and economic-social contexts that frame them, has been significantly influenced by certain contributions of Marxism.

And so, by recovering the essential background of the division into social classes and the class struggle, and also the location of these mentalities within the social totality as a whole, this history of the phenomena of mentality is much closer than the other models to the old perspectives of global history defended and promoted by Marc Bloch, Lucien Febvre and Fernand Braudel.

And although it is certainly not, far from it, a Marxist history, strictly speaking, it will be a model of the history of mentalities that will not have many echoes in the pages of the third Annales, which will more abundantly welcome other variants of this same history. This does not prevent the fact that certain works by Jacques Le Goff, as in the case of his book The Birth of Purgatory, can also be included within this fourth model.

5.

Finally, a model of the serial and critical history of mentalities can be illustrated, for example, in the book by Michel Vovelle, Pitié Baroque et deschristianisation en Provenze au xvi siecle. A history of explicitly Labroussian affiliation that has attempted to approach this so-called "third level" of mentalities with all the tools and supports of quantitative and above all serial history, while recovering in a much more explicit and central way all the critical apparatus of Marxism, to introduce it as a fundamental supporting element of the explanation.

A history that reassesses the link between ideology and mentalities, making an effort to locate the latter as that third level always articulated and intertwined with both the lower economic level and the intermediate level of the social. History which, while constituting another of the possible alternative models for the examination and explanation of mentalities, also manifests itself as one of the many expressions of the movement of intellectual convergence between the Annales perspective and Marxism that also developed within the general historical conjuncture of the years from 1968 to 1989.

History of mentalities and social history of cultural practices

If the history of mentalities is a clear fruit of the cultural revolution of 1968, its life curve has unfolded completely within the immediate conjuncture opened by that same date and closes with the also symbolic and emblematic fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

For if, as we have pointed out, the criticisms of the term mentality and the history of mentalities begin with the very emergence of this historiographic genre, it is clear that they reached their full apogee during the 1980s. And so, in the 1970s, despite its ambiguity and lack of definition, mentalities became the most common type of historical practice in France and to some extent in Europe, and later throughout the West and the world, in the 1980s, on the other hand, criticism of this history of mentalities increased enormously, causing a progressive abandonment of this semi-amorphous concept and this type of history, which was increasingly relegated by an important sector of the historians' guild.

In the second half of the 1980s, this history of mentalities began to fall into disuse in France, to be gradually replaced by a new conception of this same problematic field, which is the social history of cultural practices or the cultural history of the social, promoted and exemplified by Roger Chartier and Alain Boureau, among other authors.

The decline in France and then in Europe as a whole of this history of mentalities has not, however, prevented its diffusion and even its great popularity strangely maintained to this day in places such as Spain, Latin America, and Japan, among others.

Thus, the fourth generation of Annales, which has begun to assert its project precisely since 1989, has already clearly distanced itself from this history of mentalities, welcoming in its place this new social history of cultural practices referred to above. Thus, by replacing the ungraspable term of mentality with the more precise and rigorous concept of "cultural practices", the authors of this fourth generation of Annales will be able to propose a vision of cultural themes in which the interconnection of that culture with its social and material environment becomes obligatory, while at the same time opening its operationalization to be able to reflect the diversity, within the same society, of the different cultural expressions of the classes and social groups that constitute it.

Because as opposed to the concept of mentality, which has a totally undefined and therefore random relationship concerning its general social context, the concept of differentiated cultural practices refers instead, necessarily, to the very materiality of cultural processes and, consequently, both to the social and economic foundations of such practices and also to the real and concrete spaces and modes of construction of messages and ideas, together with the real mechanisms and figures of their circulation, distribution, and appropriation. In addition, and by insisting that this is a social history of these cultural practices, the indissolubly social character of culture is once again vindicated, that is, the fact that these practices are always cultural expressions of the social realities and phenomena themselves, to which they are linked and which they reproduce in a complex and mediated manner.

Likewise, and in this same overcoming line, the vision of a "transclassist" mentality will give way to a new approach, which, by questioning the profound differences between the multiple cultural practices coexisting in any society, will find its root in the complex differentiation and compartmentalization of society itself, which is generally and undoubtedly divided into social classes, but also and at the same time, inhabited by social groups differentiated by distinctions of social classes, will find its roots in the complex differentiation and compartmentalization of society itself, which is generally and undoubtedly divided into social classes, but also and at the same time, inhabited by social groups differentiated by the distinctions or polarities of urban and rural, masculine and feminine, old and young generations. The groups, for example, the Catholics and the Protestants, the artisan and professional strata, etc.

This leads us to a history that, in addition to recovering the cultural differences born of class opposition, is simultaneously capable of introducing the nuances derived from these other differences of social groups, which in turn are expressed in so many other equally dissimilar cultural practices. A new cultural history of the social, which, assimilating all the pertinent criticisms that ended up invalidating the history of mentalities, will constitute a real alternative to that history of the mentalities that was so successful in the seventies and eighties, and which is now definitively superseded.

Seen from a more global perspective, the concept of mentality was useful above all as a critical instrument that made it possible to denounce and highlight the enormous limitations of the traditional and already anachronistic history of ideas. Also interesting was the effect it had on historiography and the social sciences, in the sense of opening up and providing access to new topics and fields of research, previously relegated or little frequented by social scientists, and which the cultural revolution of 1968 forcefully reintroduced into the essential and daily agenda of these historians and social scientists.

However, as a concept that is more connotative and descriptive than analytical and rigorous, the term "mentalities" soon showed its limitations and inadequacies. And although it still enjoys great popularity today in Mexico, Spain, and Latin America, it is useful to remember that in France and much of Europe it has already been completely superseded, to yield its place to that new social history of cultural practices whose recovery and assimilation constitutes one of the most important intellectual challenges for historians and social scientists who today deal with these complex issues of culture and human cultural phenomena.

Author: Carlos Antonio Aguirre Rojas, Source: Correo del Maestro No.38, pages 13-25.