How Spanish Women Found Their Beat in Mexican Exile

The Spanish Civil War led to an exodus of thousands seeking refuge from Franco's dictatorship, and among them were women whose stories have often been sidelined. Mexico didn't just offer asylum; it became a canvas for Spanish women to challenge patriarchal norms and reimagine their roles.

In the annals of modern history, the Spanish Civil War occupies a distinct chapter, fraught with ideological battles, cultural schisms, and a protracted human toll. When General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces claimed victory in 1939, a mass exodus ensued—thousands fled the impending repression and persecution. Among them were women, whose stories are often submerged beneath the broader geopolitical narrative. Yet, a closer examination reveals that their experiences in exile, specifically in Mexico, offer critical insights into the resilience and ingenuity of Spanish women under the constraints of patriarchal norms.

The gravity of the human crisis invoked an international response. Countries like France, Belgium, the USSR, and notably Mexico, became sanctuaries for Spanish refugees. One striking example is the 1937 journey of the “Children of Morelia,” a group of 456 children—157 of whom were girls—that sailed from France to Mexico. However, it was post-1939 when Mexico witnessed a more significant influx of Spanish asylum seekers, catalyzed by the formal end of the civil war.

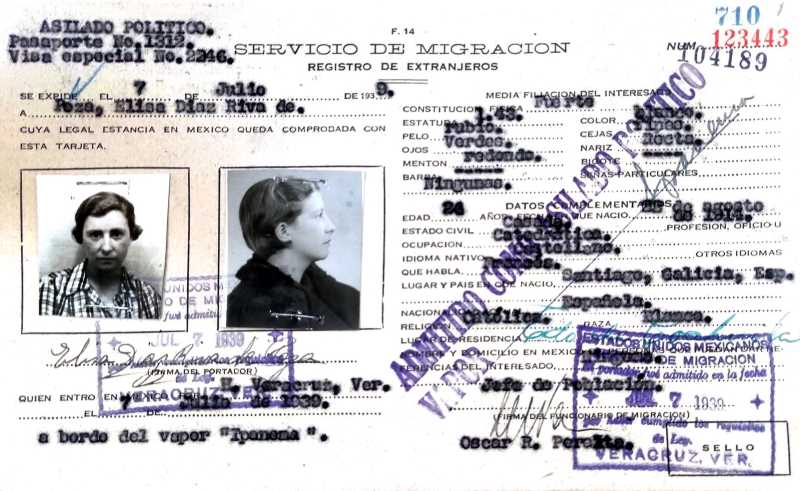

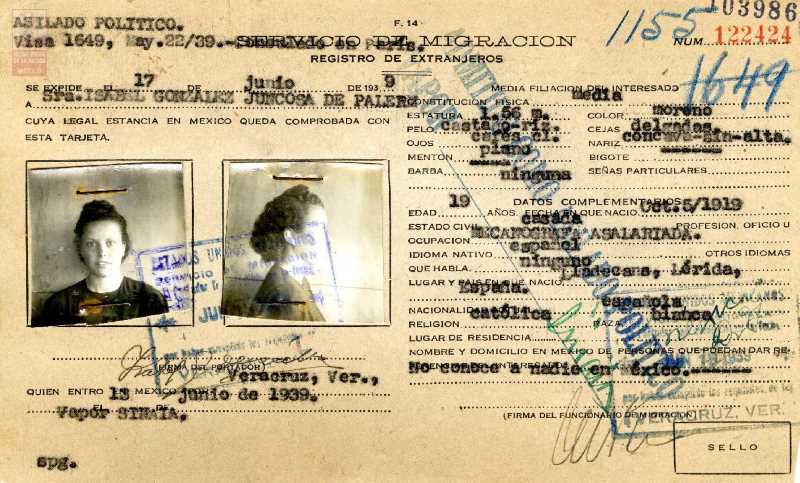

The Mexican government went beyond mere platitudes of solidarity; it set up extensive databases through its Ministry of the Interior's Department of Migration. These records have become vital historical repositories, residing in the AGN (General Archive of the Nation), and are particularly useful for scrutinizing the gendered dimensions of this mass relocation.

A study of approximately five thousand identification cards from 1939 reveals the gendered division of labor within the exiled Spanish community. Historian Pilar Domínguez Prats observes that 57% of women asylum seekers reported domestic work as their primary activity. Such figures reiterate how a patriarchal society assigned labor roles that minimized women's economic contributions, relegating them to unpaid domestic chores.

However, the resilience and ingenuity of these women emerged as they adapted to their new circumstances. About 43% ventured into other economic activities like dressmaking (12%) and professions such as typists and teachers (5% each). This diversity not only reflects their skills but also an act of resistance against gendered constraints.

The Cultural Vanguard

Astoundingly, despite societal barriers, some women managed to break through the male-dominated professions. A critical subset of this female diaspora comprises journalists, writers, artists, and professors. These were the luminaries who contributed substantially to the intellectual and cultural tapestry of both Spain and Mexico. They were the torchbearers of an “outstanding generation” of Spanish women in exile, whose legacies extend beyond mere numbers or statistics.

Equally compelling is the educational appetite among the young female asylum seekers—almost 10% of whom declared themselves as students. This surge led to the establishment of schools and colleges by the Spanish exile community in Mexico, creating pathways for women to complete their studies successfully.

For many, the dream was always to return to Spain—a dream deferred by the longevity of Franco's dictatorship. Yet, Mexico offered more than just refuge; it provided a new landscape where these women could reimagine and rebuild their lives. It became a permanent home for some, underlining the transformative capacity of migration in reshaping destinies.

The Spanish Republican exile in Mexico is not a monolithic tale of escape and survival. When viewed through a gendered lens, it evolves into a complex narrative that foregrounds the unique challenges and triumphs faced by Spanish women. It serves as a poignant reminder that behind the seismic shifts of geopolitics lie micro-narratives of resilience, ingenuity, and quiet rebellion—each deserving its place in the expansive mosaic of human history.