The modern codices of the Tlaxcalan history of Xochitiotzin

Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin is considered a member of the second generation of fresco muralists. His work portrays the festivities, customs, and traditions of his land.

Before the arrival of the Spaniards to Mesoamerica, Tlaxcala, formed by the lordships of Tepeticpac, Tizatlán, Ocotelulco, and Quiahuiztlán, managed to remain an independent nation from the great dominion that the Mexicas had established.

This enmity between the Tlaxcala people and the Mexica was used in their favor by Hernán Cortés upon his arrival to the territory since he found in that conflict the possibility of having on his side a warlike ally that would allow him to occupy Tenochtitlan and other territories. The Tlaxcalans agreed to become allies of the Spaniards, but not without first confronting them arduously.

After the fall of Tenochtitlan, and as a form of gratitude for their military collaboration, Spain gave some prerogatives to Tlaxcala, such as the preservation of its indigenous government, the granting of a coat of arms, and the appointment of the Loyal City of Tlaxcala, which was founded around 1535 and became the seat of the first bishopric of New Spain.

The work done on behalf of the conquistadors was also reflected in the exemption from payment of taxes and other privileges. However, with the advance of the viceroyalty, these pardons faded away.

This passage summarizes the long and complex history of the people of Tlaxcala and is reflected in the walls of the Government Palace of Tlaxcala, a building erected in the mid-sixteenth century that housed the Royal Houses. These murals made by the artist Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin have become, according to the anthropologist Laura Collin Harguindeguy, the Tlaxcala version of the history of the conquest.

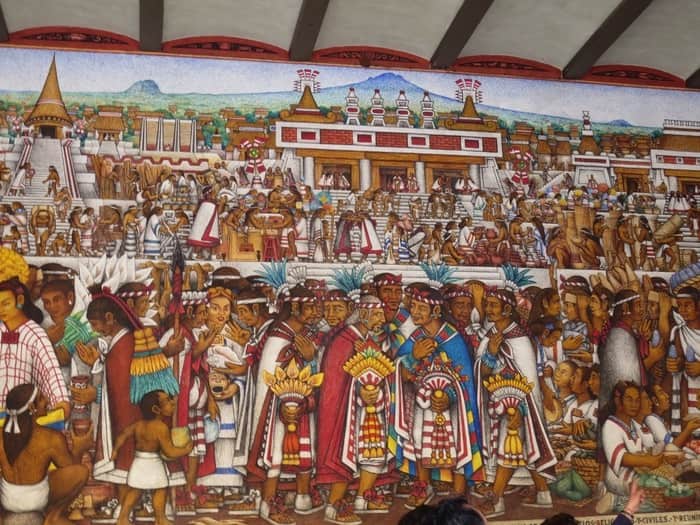

It is a pictorial version of the long Tlaxcalan past that presents Tlaxcala as the cradle of the Mexican nation and masterfully captures the cosmovision, organization, rituals, legends and facts that constitute the Tlaxcalan nation; as well as the mestizaje and cultural syncretism. The mural work unfolds over 450 square meters and is divided into 24 segments that begin with the arrival of the first settlers to America, passing through Independence, the Porfiriato and culminating in the late nineteenth century.

"There is no recognition of the Tlaxcalans. That was invented by the madman of Fray Servando and Bustamante. They said that Independence was the shake-up of the conquest of the Spaniards and the expulsion of the tyrants. Then, the Tlaxcalans, allies of the Spaniards, were left as traitors," said Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin himself when explaining his mural work in an interview with Armando Ponce in 1990, when the mural work had not yet been completed in its entirety.

He adds: "But before the arrival of the Spaniards there was no Mexico. What the Tlaxcalans wanted was not to conquer Mexico, but to be free again. During 62 years of the Aztec siege, the Tlaxcalans did not eat salt, although salt is very important for the body. Those years, however, served to shape them as a nation. The Tlaxcalans had coordination between the powerful and the people, democratically, between the macehual and the lord. Otherwise, they would not have survived.

Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin is considered a member of the second generation of fresco muralists and his work, artistically influenced by painters such as Francisco Goitia, Guadalupe Posada, Diego Rivera, and Agustín Arrieta, portrayed the festivities, customs, and traditions of his land.

Besides being a painter, Xochitiotzin worked as a draftsman, engraver, writer, professor, restorer, researcher, and chronicler.

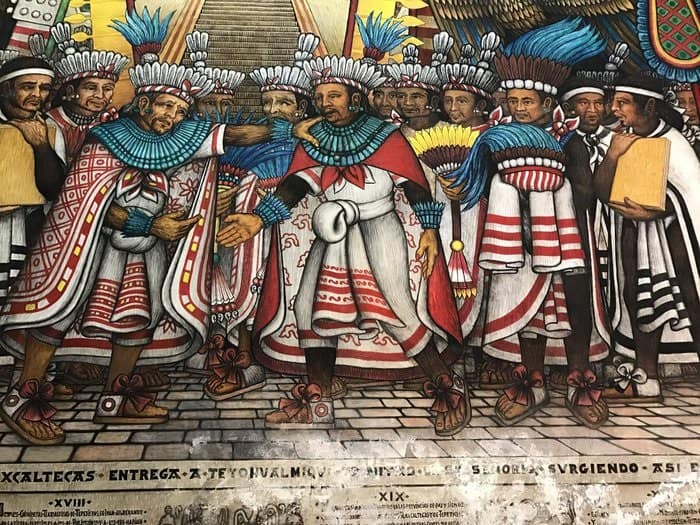

Elaborately, the murals on the ground floor tell the arrival of the Nahua people to the Valley of Mexico and their encounter with the mythical eagle; they also narrate the foundation of the four lordships of Tlaxcala and refer to some important warlike events, such as the conquest of Texcoco by Nezahualcoyotl, the wars in flower, the enmity with the Mexicas, the battle of Atlixco and the sacrifice of Tlahuicole.

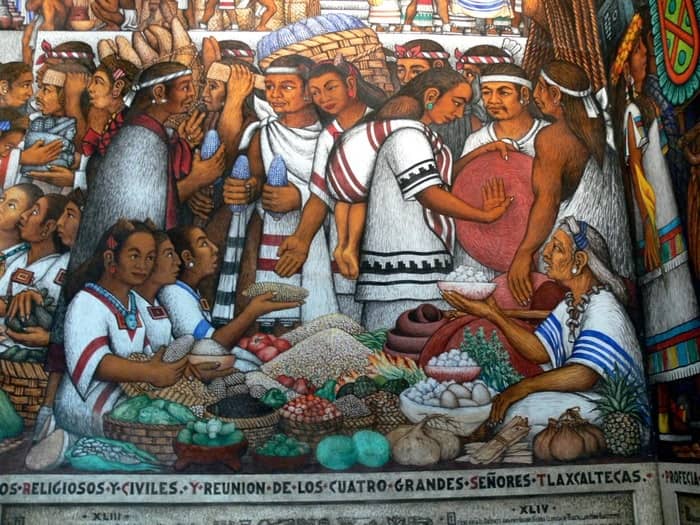

The daily life and worldview of these people are addressed in the murals about the cult of Camaxtli, the god of the Tlaxcalan war, and the festivals dedicated to Xochiquetzal, goddess of dance, music, and crafts; then we find the narration of the myth that explains the discovery of corn, the explanation of the use of maguey and various scenes that account for the commercial practices in the market of Ocotelulco. Later, the alliance established between Spaniards and Tlaxcalans towards the conquest of Tenochtitlan is addressed.

Finally, in the monumental staircase of the enclosure, the prophecy of Quetzalcoatl's return, the arrival of Cortés to Veracruz, the evangelization and the events after the conquest can be appreciated. These great segments are known as The Tlaxcala Golden Century and From the Century of Lights to Porphyry in Tlaxcala and Mexico.

At the bottom of each of the scenes, there are texts based on the sources of the colonial chroniclers that detail the historical moment that the murals depict. This pictorial conjunction with the text makes Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin's work a kind of modern codex that presents a different vision from that of the Mexican history of the conquest.

The history printed on the murals of the Palace of Tlaxcala recognizes the Spaniards as a fundamental part of the national identity and puts mestizaje at the center, presenting Tlaxcala as its cradle. Precisely, some scenes on the walls portray figures that allude to mestizaje and its importance for the Mexican nation. One of them is the Malinche, who is represented on tape accompanying Hernán Cortés.

"The Tlaxcalan version of the conquest also represents a founding myth, a historical myth with its stages or cycles, that of the indigenous era and that of the mestizo era, of which the Tlaxcalans appear as the progenitors, as allies of the Spaniards. Consequently, the Tlaxcalan version does not deny the Spanish heritage or evangelization, on the contrary, it claims it and incorporates it as part of its history," says Laura Collin Harguindeguy.

Furthermore, she points out: "It constitutes an alternative version, a regional history, which corresponds to a people opposed since pre-Hispanic times to the Mexicas-Tenochas, who managed to acquire privileges of autonomy and for whom the conquest does not represent a trauma, but in any case a liberation, and therefore a good business. As every myth is ambiguous, and its contradictory episodes glorify Xicoténcatl the young man, for having opposed the alliance, and at the same time the alliance itself.

The project for the realization of these murals, executed in fresco, began to be forged in 1953, but they were not begun until 1957. The first stage of this company lasted 10 years, during which time Hernández Xochitiotzin researched, designed and made the sketches that would become the beautiful images that cover the walls of this venue, which has become a work of invaluable artistic and cultural value.

The work extended for 35 years until 2000 when Hernández Xochitiotzin made the sketch for a work entitled Cristóbal Colón a Tierras Mexicanas, which was to become the last mural in this complex. However, in 2001 the painter decided to retire permanently due to health issues and six years later he died at the age of 85.