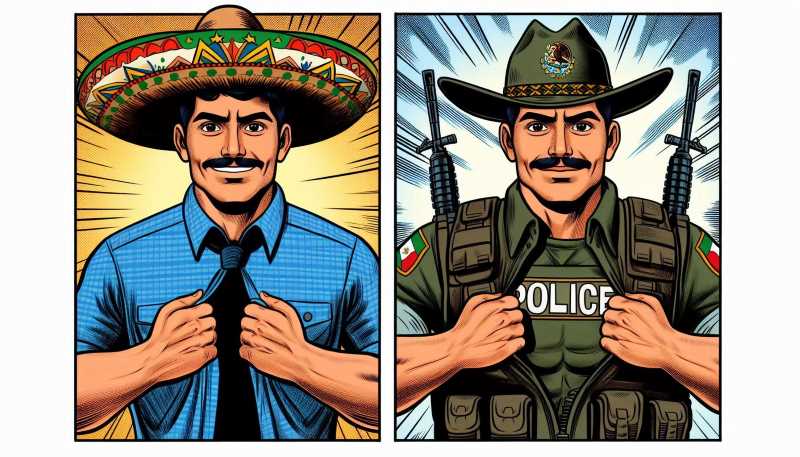

The National Guard, Part Army, Part Police, All Confusion?

The Constitutional Points Commission approved reforms to place the National Guard under the Secretariat of National Defense, making it part of the permanent Armed Forces. This decision has sparked controversy, with critics arguing that it militarizes public security.

The recent approval by the Constitutional Points Commission of the Chamber of Deputies of a proposal to incorporate the National Guard into the Secretariat of National Defense (Sedena) marks a significant turning point in Mexico's ongoing struggle with crime and violence. This decision, which would effectively place the National Guard under military command, has sparked heated debate among lawmakers, security experts, and civil society organizations, raising concerns about the erosion of democratic institutions, the potential for human rights abuses, and the long-term implications for public safety.

The proposal, which would amend various articles of the Political Constitution, has been championed by the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador as a necessary measure to combat the rampant crime and violence that has plagued Mexico for decades. The government argues that by militarizing the National Guard, it will be better equipped to tackle the complex challenges posed by organized crime, drug cartels, and other criminal elements.