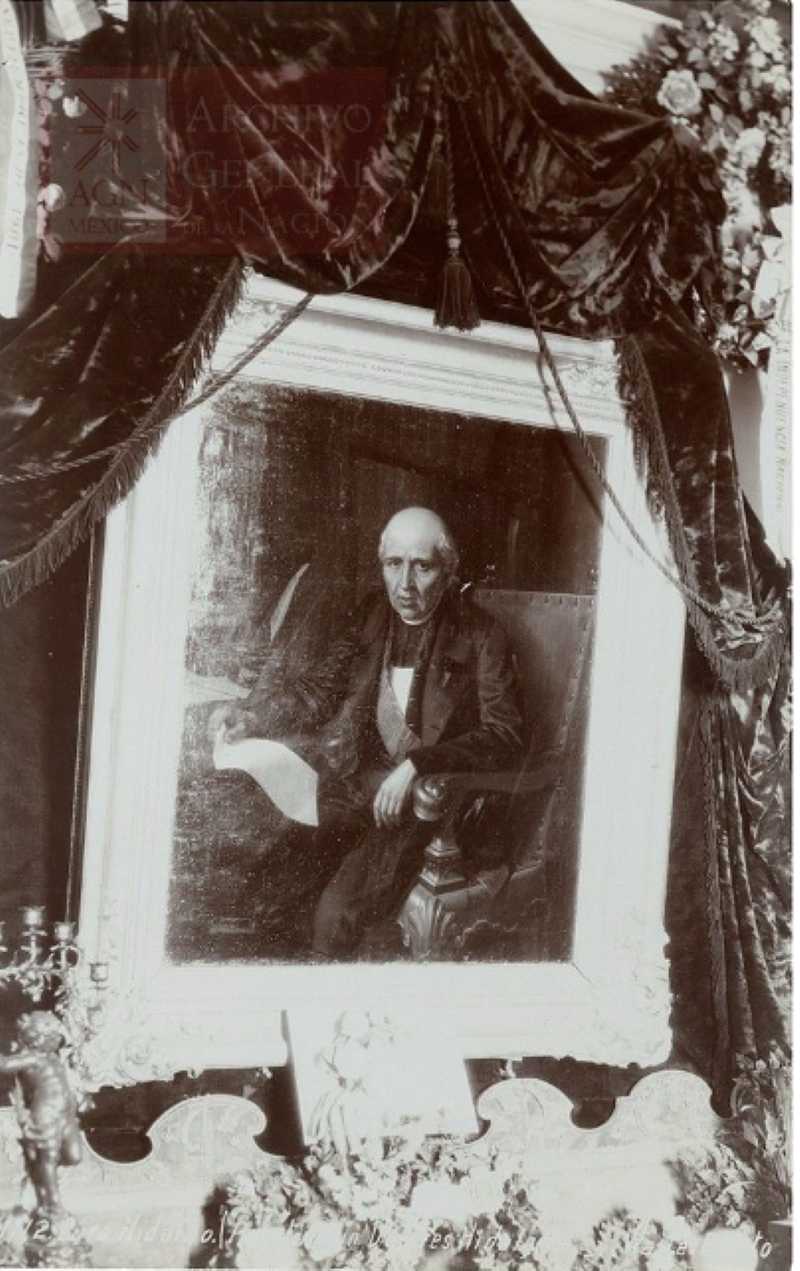

The Priestly Rebel Who Gave Spain a Mexican Headache

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a priest, led Mexico's independence movement in 1810, boosting local economies with silk and pottery. His revolutionary actions are documented in various historical records, showcasing his role in liberating Mexico from Spanish rule.

Let’s talk about Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a man as complex as he was revolutionary, and whose life story has been wrapped, almost strangled, in so much myth and patriotic embroidery that getting to the core of who he truly was is about as difficult as unearthing a lost sock from a tumble-dryer. But if you’re willing to rummage through dusty archives and stacks of yellowing papers, you'll find a story worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster—or at the very least, a ten-part Netflix drama that leaves you simultaneously inspired and exasperated.

Where do we start with Hidalgo? His full name is so long it might as well be a prayer: Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga. Imagine being called on to dinner as a child—poor lad must’ve arrived at the table famished just from hearing his name. Hidalgo was born into what you'd charitably call a "modest" family. His father, Cristóbal, and his mother, Ana María, weren’t exactly rolling in silver coins, and neither were they impoverished enough to be the kind of downtrodden, Dickensian peasants you'd feel compelled to write heartfelt poems about. They were squarely middle-class by colonial standards, which in 18th-century Mexico meant they had enough to get by but were far from being dripping with wealth.