The Secret Life of Don Dieguillo, the Indigenous Leader Who Outwitted an Empire

In the scorched deserts of colonial Mexico, one Indigenous leader—branded a traitor, hunted by governors, and betrayed by history—outwitted the Spanish Empire with nothing but cunning, faith, and an unshakable will to survive.

In the early winter of 1718, Spanish authorities in Coahuila, a frontier province of New Spain, compiled a damning legal dossier. Under solemn oath, with their hands placed on a cross, a parade of Spanish settlers testified against an indigenous leader named Don Dieguillo. Their accounts painted a fearsome portrait: here was a cunning traitor who had feigned friendship and Christianity only to betray his benefactors.

He was accused of leading a coordinated attack on the Franciscan missions of Santa Rosa and San Buenaventura, of stealing sacred jewels, kidnapping two children, and brutalizing a priest. The testimony was overwhelming, conclusive, and officially recorded for the viceroy in Mexico City. One witness declared Don Dieguillo "one of the most astute Indians known since Moctezuma"; another called him "one of the most bellicose and industrious... known in the Indies".

The case was closed. Don Dieguillo was a villain, a rebel against the Crown, an apostate who had destroyed lives and property. The story, cemented in sworn testimony, seemed just another tragic chapter in the violent history of the Spanish conquest.

There was just one problem: it was all a lie.

Centuries later, buried in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville, Spain, another manuscript surfaced. This document, dated 1692—a full 26 years before the alleged crime—tells a diametrically opposite story. It is an official report from General Juan Fernández de Retana, the captain of a presidio hundreds of kilometers away. Retana details an attack he launched on an indigenous group known as the Chizos. After a "cruel slaughter," his men inspected the Chizos' belongings and found a trove of stolen Spanish objects: jewelry, sacred vestments, a missal, and, most tellingly, an official document. It was the formal appointment of one Don Diego de Valdés (Dieguillo) as the Governor of the Indigenous Pueblo of Santa Rosa de Nadadores, signed by the Viceroy of New Spain himself.

The Seville manuscript unraveled the entire 1718 case with one stunning revelation. Don Dieguillo was not the perpetrator of the attack on the missions; he was one of its primary victims. The Chizos had not only looted the missions but had also robbed Dieguillo, stripping him of his official title and stealing his team of oxen and farming tools. The men who swore on the cross in 1718, from the provincial governor on down, had all committed perjury.

This discovery transforms the story from a simple tale of frontier violence into a complex conspiracy, exposing the rampant corruption, greed, and startling injustices that defined life on the edge of the Spanish empire. At the center of it all is a remarkable figure who lived for nearly a century, a leader whose true story was almost completely erased by those who sought to profit from his downfall.

The Man Behind the Frame-Up

To understand the conspiracy, one must understand the motive. The man who orchestrated the false accusations in 1718 was Joseph Antonio de Eca y Múzquiz, the governor of Coahuila. His goal was not justice; it was land.

Missions in New Spain were built on a specific legal foundation. They existed for the purpose of converting indigenous people (referred to as gentiles) to Christianity. A successful mission, after a period of conversion, could lead to the establishment of a "Pueblo de Indios," a semi-autonomous indigenous town with its own governor and council, a system designed by King Philip II as an alternative to outright slavery or the brutal encomienda system. So long as indigenous people lived on the land and were part of the mission system, the land belonged to them under the protection of the Church.

Governor Eca y Múzquiz saw an opportunity. By officially branding Don Dieguillo a rebel and an enemy of the Crown, he unleashed the full power of the colonial state against him. The viceroy, Fernando de Alencastre, Duke of Linares (who, in a darkly ironic twist, was already dead when he was cited as a witness in the 1718 case), had previously issued a chilling order for the governor of Coahuila to bring him "the head of Don Diego and the other heads of his partisans, dead or alive".

Facing a death sentence, Don Dieguillo did the only thing he could: he fled, and nearly all the indigenous people of the missions followed him. With the flight of its indigenous population, the mission ceased to legally exist. Governor Eca y Múzquiz promptly declared the lands realengas—royal property—and, acting as the king's representative, granted them to a new owner: his own son. The frame-up was complete. It was a cold, calculated act of bureaucratic violence, a stark illustration that a document, even a colonial-era legal file, cannot be taken at face value.

A Life on the Frontier

So who was the man they tried so hard to erase? The historical record, patched together from disparate and often contradictory accounts, reveals a leader of immense influence and resilience. According to a letter sent by a viceroy to the King of Spain, Don Dieguillo declared in 1680 that he was 60 years old, placing his birth around 1620. He lived to be nearly 100, his life spanning a period of catastrophic change for the peoples of the region.

He was a man of multiple identities, a reflection of the fluid social landscape of the time. The Spanish referred to him by various ethnic affiliations—Cuechale, Hueyquechale, Nadador, Bobol—often confusing a person's place of residence with their tribal nation. He operated across a vast territory that defied the tidy provincial borders the Spanish tried to impose, appearing in records from Nuevo León, Nueva Vizcaya, and what would become Texas. He and other indigenous leaders "developed a series of actions that far overflowed what at the time was Coahuila".

This constant movement was a strategy for survival. By shifting between different jurisdictions—the Province of Coahuila, the Kingdom of Nueva Vizcaya, the New Kingdom of León—he expertly played the competing Spanish authorities against one another, seeking refuge in one when persecuted in another. When Governor Eca y Múzquiz drove him from Coahuila, he fled to a presidio near the Nazas River, under the authority of Nueva Vizcaya.

His life was a negotiation between two worlds. He adopted Christianity, at least outwardly. He was married twice in the church in Parras, first to a woman named Isabel and, after she died, to another named Dorothea. At the same time, he never fully abandoned the world of his ancestors. When he and his uncle, Don Esteban Hueyquetzal, were forced into the encomienda system—a form of indentured servitude—on the estate of a Spanish woman, they soon left without notice. A Spanish scribe, failing to grasp their perspective, wrote that Don Esteban chose to leave a life of "food and clothing" to "return to his natural and evil life," a life the chronicler revealingly defined as "his liberty".

The War for Souls and Symbols

Don Dieguillo lived in a world where spiritual and earthly power were inseparable. The Spanish conquest was not just a military campaign; it was an attempt to colonize the minds and souls of the indigenous people. Yet the native peoples were not passive recipients of this new religion. They questioned it, resisted it, and, in a brilliant display of cultural adaptation, appropriated its symbols for their own purposes.

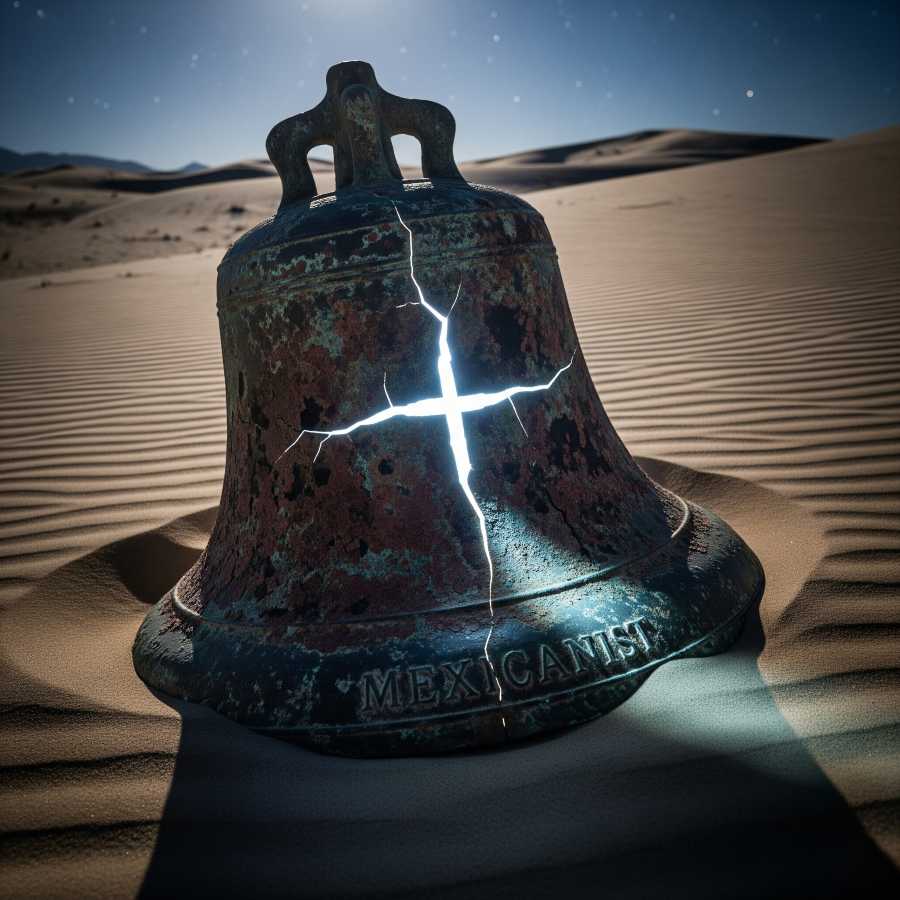

In one extraordinary account recorded in 1681, Don Dieguillo himself testified about an incident involving a mission bell. During a missionary's absence, several indigenous groups—Hueyquetzales, Yoricas, Pinanacas, and others—decided to destroy the object that dictated their new lives, calling them to labor and catechism. They pulled the bell down and, gathering stones, began to dance around it in their traditional way, "making a mockery of said bell, stoning it and striking it many blows to break it". They continued all night, but the bell would not break. By morning, a terrifying scene unfolded: "more than twenty Indians had died, not counting many more who were found maimed and lame and others crippled in their entire body".

The story reads like a medieval fable of divine retribution, a "miracle" designed to showcase the power of the Christian God. But it also reveals a profound indigenous frustration with the tyranny of colonial time, represented by the bell that fractured their world "into pieces with only its sound".

This appropriation of symbols could also be turned into a weapon. One account tells of an indigenous leader named Nicolás el Carretero, a relative of Dieguillo's, who devised an ingenious trap. An indigenous man approached Captain Alonso de León and told him that the Virgin Mary was appearing to his people in the wilderness and that she wanted the Spaniards to come and see her, "three by three". It was, the Spanish chronicler noted with grudging admiration, a fiction "prepared by the cunning and malice of said Indian" to lure the soldiers into an ambush.

These stories reveal a world of immense complexity, where the lines between conversion, co-option, and resistance were constantly blurred. The indigenous peoples of Coahuila were not simply victims. They were active agents in their own history, fighting for survival with every tool at their disposal—from the bow and arrow to the very symbols of their conquerors' faith.

Don Dieguillo’s final years were spent in exile, under the protection of a Jesuit priest and the authorities of Nueva Vizcaya. He was an old man, nearly a century old, but still a figure of immense authority. The last mention of him in the available records is from 1717. After that, he vanishes from the written history, his final resting place unknown.

He was a survivor, a leader who navigated a century of violence and upheaval, only to be vilified by a corrupt official for personal gain. His story, rescued from oblivion by the patient work of historians sifting through archives on two continents, is a powerful reminder that history is never a closed case. It is a story of how easily the truth can be buried by power and greed, and how, sometimes, with time and immense effort, the ghosts of the past can be brought back into the light.

Source: Valdés, Carlos Manuel, and Celso Carrillo Valdez. Entre Los Ríos Nazas y Nadadores: Don Dieguillo y Otros Dirigentes Indios Frente al Poderío Español. Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, 2019.