About the tongue: what a wonder muscle it is

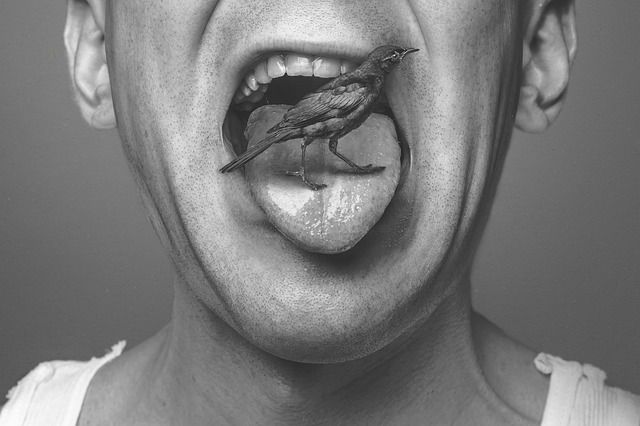

Have you ever wondered what happens to the tongue, the muscle through which we perceive the flavors and textures of our food, when we expose it to a storm of substances with extreme flavors?

Eating our favorite foods is one of life's greatest pleasures; there is no doubt about that, but have you ever wondered what happens to the tongue, the muscle through which we perceive the flavors and textures of our food when we expose it to a storm of substances with extreme flavors?

Ricardo Reyes Díaz, Belinda Vallejo Galland and Aarón González Córdova, academics from the Center for Research in Food and Development (CIAD), specialists in food sensory analysis, the branch of science dedicated to analyzing the consumer's response to the sensory attributes of food through the senses, give us some recommendations for treating our tongue well.

How do we perceive flavors?

The tongue is covered with microscopic-sized taste buds or taste buds consisting of chemoreceptor cells. There are approximately ten thousand taste buds in the mouth, although their number eventually decreases with age (there are also some taste receptors scattered in other parts of the mouth, such as the palate).

These taste buds allow us to detect the basic or primary tastes: sour, sweet, salty, and bitter; in addition to these, umami, metallic and astringent have also been included (Lawless and Heymann, 2010), whose perception is located in certain areas of the tongue. These stimuli (tastes) are directly related to the concentration of a certain substance present in the food we eat.

Taste stimuli interact with receptors through various transduction mechanisms to convert the chemical stimulus into a response (taste perception). In addition, there is information transmitted from the common chemical sense; this system is separate from the taste system and in humans consists mainly of the trigeminal nerve in the head and its free nerve endings in the mouth and nasal cavity (Coren et al., 2001).

Both the sense of taste and the common chemical sense are sensitive to a wide variety of stimuli; among them, certain flavors that allow us to remember passages of our life since childhood, to avoid consuming what we dislike or to be alarmed by something that may put us in danger, but, above all, to enjoy the diverse pleasures of tasting the preferred food, beyond its nutritional contribution as a means of survival.

Taking care of the tongue

The tongue is one of the most amazing and curious organs of the human body, since thanks to it we can perform different activities such as talking, chewing, swallowing, and tasting things; however, because it is also a very sensitive organ when consuming certain foods (for example, hot, acidic or spicy foods), people can experience certain alterations or reactions in it, such as irritation, pain, and burning sensations.

It is very important to identify the origin of the symptoms of alterations in the tongue, and in case the cause is an irritating food, we should eliminate or reduce its consumption. Otherwise, it could be an allergy, infection, or disease that should be treated medically.

By tasting things with the tongue, we experience the great capacity of taste that allows us to enjoy and differentiate foods. However, the tongue is more versatile than that. It is also sensitive to temperature and pressure. It also can detect various chemicals that mimic these two sensations and are found in a large number of foods. This last group of sensations is called chemostasis.

There are other sensations such as refreshing (of cold) or umami (of delicious attributes) that provide an important contribution to the perception of taste in food. In addition to these, there is also the spicy sensation, which is very common in Mexican and Oriental food. The latter sensation has a "burning" characteristic and is difficult to separate from those produced by general chemical irritation effects and tear effects.

There are spicy foods, such as chili, which is one of the main ingredients in Mexican dishes, and others such as black pepper, ginger, mustard, radish, onion, garlic, or aromatic spices such as cloves and cinnamon that are added to foods to increase their palatability and acceptability. Among the substances responsible for these spicy sensations is capsaicin, a molecule that gives chili peppers their particular taste. The same happens with piperine in black pepper and allyl isothiocyanate in mustard and radishes.

Such foods feel spicy because they bind to receptors on cells that are activated promoting a reaction resulting in the elevation of temperature in the area of contact. Similarly, sour-tasting foods send "pain messages" to the tongue, presumably to warn us that it is not a good idea to eat them.

However, it is important to mention that capsaicin and other spicy foods will not harm your tongue; in fact, you may notice that, after eating a lot of spicy food, the burning will no longer affect you as much, as the receptors eventually stop giving such a strong response to the compound. The phenomenon is called capsaicin desensitization and is something that has been of scientific interest suggesting that capsaicin may relieve pain.

The efficacy of taking various liquids into the mouth to relieve the itch of food depends, to some degree, on its taste. The most effective liquid should taste sweet (e.g., mineral water or sparkling water) or sour (e.g., juice of some citrus fruit) and should be at a cool temperature that can give a sensation of cooling effect.

Lovers of joyful experiences

Today, as a result of globalization, consumers are developing a special taste for foods with strong, exotic, and unusual flavors, which is why exaggeratedly spicy or very substantial products are experiencing an upward trend in consumption.

All this range of varieties and intensities of flavors and aromas are related to the intensity of a neural activity produced by the stimulus (taste), which results in new sensations that are experiences that we commonly seek to repeat. These sensations and their intensities usually depend on the concentration of the provoking substance; however, perception can be influenced by age, sex, habits, and emotional state. For example, it is known that children express a strong preference for sweetness and rejection for bitterness. The bitterness in caffeine and beer is usually detected up to six times less intensely in adults than in young people.

Experts believe that there are evolutionary reasons for this since while most toxic substances present in nature are bitter, sweet products tend to be nutritious and rich in calories. In other words, the sense of taste protects us and contributes to our development.

Scientific studies show that there is a decrease in the perception of sweet and salty tastes with age so that as this increases, greater concentration is necessary to differentiate between salty and sweet intensities, which is probably a consequence of the degeneration of the taste buds (González et al., 2002). In children, these papillae regenerate every two weeks and are well opened, which allows tastes to be experienced with great intensity. As we get older, the number of taste buds decreases, and, in addition, they tend to be more closed, so the potency of taste declines.

The fact that many things we did not like as children are attractive to us as adults maybe because people lose olfactory sensitivity as they get older, which is an important reason why many people seem to outgrow childhood aversions. Thus, a food whose odor was too intense for a child becomes mild as an adult. In addition, as we grow older, we become more aware that a rejection of food may be irrational and, as a result, we make an effort to like it, since we have a greater capacity to reflect on the cause of the aversion and give the food in question a second chance.

Recovering old sensations

Various processed foods may contain high concentrations of additives, such as sugars, fats, and salts, to make them more appealing to the consumer, which can lead to changes in sensory quality, as foods and beverages will not be enjoyed in the same way when they are home-made.

The (unconscious) habit of consuming high concentrations of these types of additives means that, when we feel that the food lacks flavor, we tend to add more sugar or salt: this can lead to dangerous excesses. In addition, excessive intake of some additives can cause digestive problems, irritation, and allergic reactions in consumers who are sensitive to them.

Fortunately, a healthy alternative that we can undertake may be to reduce as much as possible such additives in the production of industrialized foods or to reduce the consumption of this type of food. Perhaps in this way, we can recover old sensations of taste and aroma and even discover new ones.