Feathered Heritage: The Quest to Promote Turkey Consumption in Mexico

Discover the rich history and cultural significance of the turkey in Mexico, and learn about the current efforts to promote its consumption and preservation as a vital source of meat and national heritage.

The huexolotl, better known as guajolote or turkey, which many families consume during the Christmas season, is Mexico's first domestic animal and also part of the country's essence, although few Mexicans value it as an element of national heritage, said Raúl Valadez Azúa, an academic at UNAM's Institute of Anthropological Research (IIA).

It is a gift from the Mexican nation to the world because it is produced and consumed on all five continents. "Every turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) that exists is a descendant of those that were raised in the center of the country" three thousand years ago. Although they were important in ancient times, they have yet to become known for what they are: an animal deeply linked to Mexican culture.

Even though it is not in danger of extinction (because as a domestic animal it depends on human management), it is found in reduced quantities compared to other poultry such as roosters and hens and requires rescue programs to encourage its consumption, valuation, knowledge, and traditions; "what is necessary to integrate it into our daily material and food habits."

According to El Sitio Avícola, turkey production in Mexico in 2021 was similar to that in 2020, but 36.5 percent below that of 2019, when it was approximately 1,477,000 birds, reported the National Union of Poultry Farmers.

In the wild, turkeys nest in the macollos, that is, in areas of high grasslands where they can hide. Five or six thousand years ago, when the life patterns of human groups were modified by forming semi-sedentary communities near bodies of water, contact with the bird was inevitable.

The settlers captured some of them, but others benefited from the human presence. People had changed this area, so there were no other birds or predators there for the birds to worry about. These animals adapted to human space for two or three thousand years before becoming tethered to it, i.e. domestic.

The Rise and Reign of the Turkey in Mexico

Most of the remains of domestic turkeys that can be identified as such can be found in the Basin of Mexico. They date back about 3,200 years. "Since that time, the human communities of this region already had this meat option available to them."

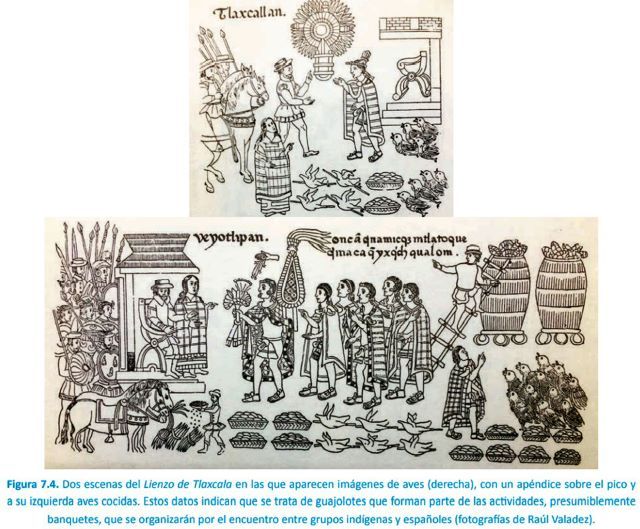

Its main use was as food; bones and feathers were also used as raw materials for the elaboration of tools, diverse objects, and ornaments. Over time, along with the material aspect, ritual schemes were created, especially those associated with gratitude to the gods. "In many pre-Hispanic practices, the sacrifice of these animals had a symbolic meaning, equivalent to the sacrifice of people."

The use of offerings, especially at funerary events, was an early practice. It is common to find burials where there are the remains of turkeys, adults or hatchlings, which served as "food" for the deceased. As time went by, it gained a place in the cosmogony of ancient Mexicans and was associated with deities such as Tezcatlipoca ("the smoking mirror", the supreme god), as can be seen in codices.

It was an important source of meat in Teotihuacan; "I am convinced that there must have been breeding farms around the city." Among the archaeological remains, it is the most abundant bird, as abundant as any mammal species (deer, rabbits, or dogs). But there is no pattern of use as part of offerings, where they are sacrificed and placed whole in a burial, at the foot of an altar, or in a ceremonial way. "Rather, they are small, scattered materials, almost always cooked, as if they had been of continuous food use," he said.

The turkey did not inhabit all of today's national territory. It is a relatively fragile animal with a high mortality rate for young, so it requires care to survive the first weeks; they are also not very resistant to diseases and environmental circumstances.

Remains of very old specimens, from two to three thousand years old, have been found, above all, in central Mexico; in one case, in Oaxtepec, Morelos; some in the central valleys of Oaxaca, in Monte Albán; and even in a place in Guatemala, El Mirador, where half a dozen remains were found and where it would seem that it was a gift between merchants or rulers.

Meanwhile, they arrived in the Yucatan peninsula approximately one thousand years ago, when the Toltecs arrived in this territory and, along with them, the breeding feet of this bird and the traditional knowledge about its management, breeding, and use. This is why these animals are used as an important source of meat in traditional Yucatecan food.

The leap to the rest of the world was made with the arrival of the Spaniards, who immediately became interested in this form of bird, which was different from the ducks, chickens, or pheasants that were known but which covered their food needs: it was a good source of meat, and since its flavor is not dominant, it is perfect for use in any dish.

After the establishment of the conquistadors in Mexican territory, it was a matter of 10 or 20 years for turkeys to reach the European courts—Spain, Italy, England, and, above all, France.

The chronicles indicate that Francis I of France ate it with special taste; Henry VIII (1521) had it roasted; and at the wedding of Charles IX of France (1570), it was part of the dishes cooked for the reception. Queen Margaret of Navarre had a farm of guajolotes in the city of Alercon at the time, so it is not surprising that 66 guajolotes were served at a dinner for Catherine de Medicis or that Pope Leo X was given several live guajolotes as a gift in 1549. Unlike other Mesoamerican animals, this "genuine Mexican" was quickly accepted and taken everywhere.

A peculiar fact is the origin of its name in English: "turkey". This took place in England and was the product of the logical question "Where do these birds come from?" with the inevitable answer, "Of course from the East!" and the obligatory interpretation: East equals Turkey, leading to the term "turkey", which would mean "the Turk".

Today, there are still rural communities where it is bred, "but it is not as intensely handled, nor does it have such a practical purpose"; for example, it is used as a gift for brides and grooms. "Traditional parts are kept, but breeders don't use it as their main source of meat every day."

The national consumption of turkey per year is almost 1.31 kilos per capita, and production is concentrated in 11 states, which have 93 percent of the total. Yucatán produces 23.5 percent, Puebla 15.2 percent, State of Mexico 14.5 percent, Veracruz 8.3 percent, Tabasco 7.0 percent, and the rest of the country 32 percent.

The Thanksgiving Turkey's Mexican Roots

According to the website Avicultura.mx, which cites the U.S. newspaper Washington Post (2019), 46 million turkeys are consumed in the neighboring country to the north on Thanksgiving Day. According to a survey by the American Farm Bureau Federation, at least 90 percent of the U.S. population celebrates that date with a special meal, and 95 percent of them include turkey.

The U.S. industry has made it a considerable source of meat that, in addition, has less fat than chicken. In Mexico, it is easier to buy frozen, smoked, or prepared turkey in a supermarket than to buy it as a ranch-raised animal, although its quality would be better. The Mexican industry gave way to international poultry consortiums, and today it is the main dish at festivities such as Christmas in most countries with a Christian tradition.

Where this did not happen was in popular culture; it is present in sayings and proverbs: "cachetadas guajoloteras"; "camión guajolotero"; "sin guajolote no hay mole, y sin maíz no hay pozole", or "te crees te crees la divina garza y no llegas ni a guajolote." And in the works of important artists such as Diego Rivera ("Campesino cargando un guajolote" an oil painting from 1944).

Just as the tradition of the xoloitzcuintle dogs was recovered and today is more integrated to our society and way of thinking, with the turkeys an effort must be made in every possible way, said the specialist.

A Book about Guajalote's Pre-Hispanic Past

The IIA published the first book dedicated to the bird, Huexolotl. Valadez and Andrés Medina Hernández coordinated the event, which also included Bernardo Rodrguez Galicia and Gilberto Pérez Roldán.

From 1996 to 2005, the university professor recalled, I wrote the first text on pre-Hispanic domestic animals, and there I included the turkey. "I became aware of the need to study not only the remains that appear in archaeological sites, but also to create a proposal, an interpretation of what these animals mean in terms of their cultural and biological history."

After five years of continuous work, the 399-page work was published in a digital version and is available on the IIA website. It is a text that breaks a series of paradigms that had been held for decades, related to the origin and the way in which the turkey was dispersed throughout the world.