"Milagritos" document the history of a community

They are usually found in galleries or museums, but their original place is in churches. In the 19th century, they became popular in Mexico because the use of sheet metal made them cheaper.

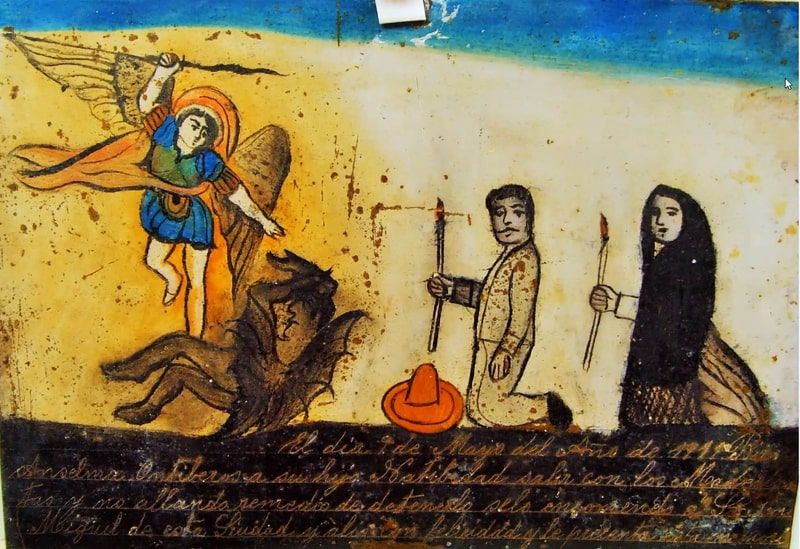

The votive offerings of the Sanctuary of San Miguel Arcangel, located in the municipality of San Felipe, in the state of Guanajuato, also known as retablos or "milagritos", are a source of information of the afflictions, hopes, and joys of the inhabitants of the Bajio of Mexico, the testimony of the unofficial history and sample of popular art. This was stated by Miguel Santos Salinas Ramos, an academic from the ENES León Unit, who added that they allow the study of aspects of history such as daily life, social organization, or religious practices of the people who donated these paintings.

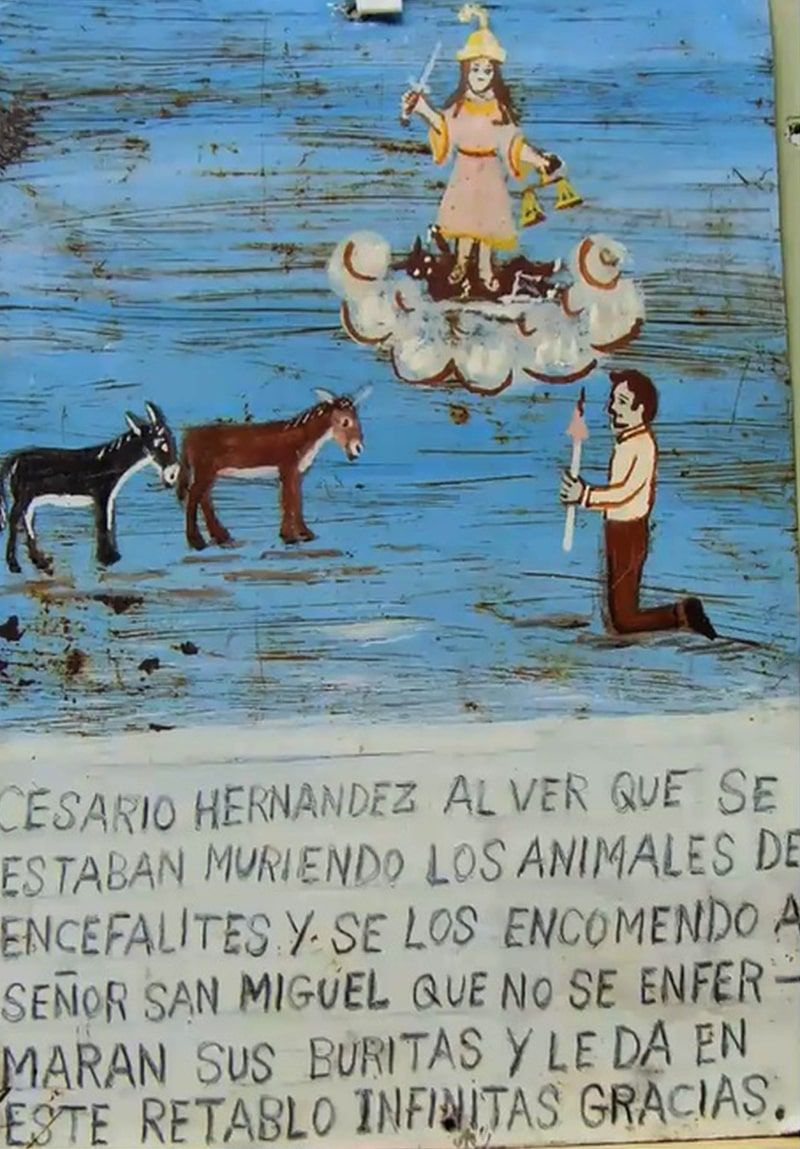

The university professor -who since 2011 has been studying the altarpieces of this church built in 1869- explained that they show the religiosity of the inhabitants of the region, how it has been urbanized and their concerns: migration, health problems, accidents, etc. Some date from 1867 and the most recent ones from 2010. "They are made of sheet metal, cardboard or wood, they are a token of gratitude to what people considered a miracle performed by the intervention of San Miguel," said the academic of the Intercultural Development and Management degree.

It is worth mentioning that soon the university expert will publish a book with a selection of 65 retablos of the more than 114 registered in the sanctuary; some present oxidation and affectations, while others are conserved under protection to avoid their theft and deterioration.

Ways of giving thanks

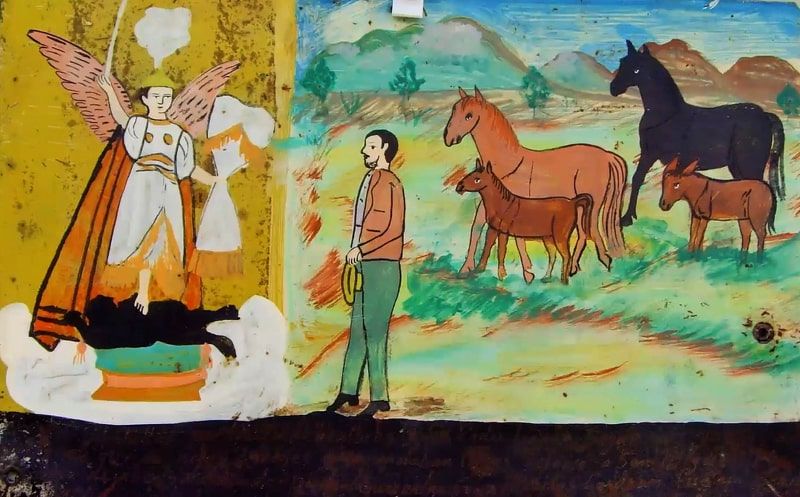

"This area until 10, 20 years ago was mainly rural, so the votive offerings show us some problems of the peasants such as the threat of losing their crops due to a drought, the satisfaction of someone because they found a stray animal or because their livestock was relieved of a disease," argued the doctor in Humanities. There are retablos of people from the north of Guanajuato, an area of migration to the United States since the beginning of the 20th century, in which they give thanks for having regularized their situation in that country or for being able to cross the Rio Bravo.

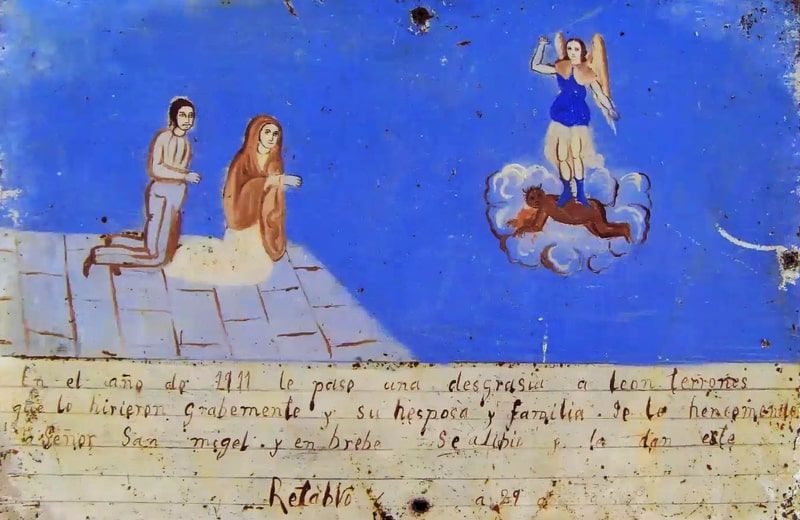

They reflect the worries, but also the hopes, the ways of giving thanks by these simple people who are not authorities and whose problems are rarely expressed in a document. There are three votive offerings about the Mexican Revolution in which, for example, a mother gives thanks that her son did not go through any trouble in a battle. Others from the 1970s and 1980s about automobile accidents show how the urbanization of cities in Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí brought other conflicts and fears for the devotees of San Miguel Arcángel.

The specialist in the History and Religious Traditions of Guanajuato emphasized that these paintings are considered sources on the history of mentalities, for addressing themes such as fears, worries, longings, and feelings. They also help to understand the participation of women in migration, health, wars, since it is common to see them in the votive offerings praying or giving thanks to their relatives. In this type of offerings, we can see the figure of the mother worried about the health of her children, the devoted wife who takes care of her husband in bed, the woman who prays for her relative not to have problems in his journey to the United States, and the countrywoman who gives thanks because an animal of her property got out of an illness.

Medieval tradition

The painted votive offerings are a tradition that emerged in Europe during the Middle Ages, in which these types of paintings were placed under or behind the altars of the churches. In the case of Mexico, people had a painting of a virgin or a saint made as a token of gratitude, but they became popular when the sheet arrived in the country.

"Originally those who made them were academic painters and many votive offerings were commissioned at the request of people who had high purchasing power, but when the plate arrived in the country, many popular painters such as Hermenegildo Bustos -whose works are now National Heritage- or Gerónimo de León found that it is a very cheap material, easy to use and began to make this type of paintings," said Salinas Ramos.

This type of artwork became popular in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century also because it was a period of numerous wars and people were thankful that their relatives did not die in those conflicts, the Cristero War, for example, in which the people of the Bajío had an important participation.

Although there are votive offerings and sanctuaries in the center and south of the country, in the west these examples of religiosity are more noticeable, and examples of this are San Juan de los Lagos, the Basilica and the Convent of Nuestra Señora de la Expectación, in Zapopan, both in Jalisco; the monument to Cristo Rey and the sanctuary of San Miguel Arcángel, in Guanajuato; in addition to the Niño de Atocha, Señor de los Plateros, in Zacatecas; plus many others.

During his studies, Salinas Ramos detected that there were painters of retablos who did not sign their pieces, but it is possible to identify that several belong to the same author due to the similarity in the images of San Miguel, in the landscape or the postures of the people. "They are an inheritance of the academic art, but captured in a popular art" because those who continued with the tradition were artists who used some patterns, copied images from 19th and 20th-century prints, he considered.

Today there are votive offerings in museums and others are sold in galleries, due to the looting of churches and in some cases due to the negligence of the authorities to take care of these expressions of religiosity. Sometimes priests remove them because they seem grotesque to them. "It is good that they are in museums, but their original place is in a church".

Origin of the San Miguel Arcangel Sanctuary

It is located in the north of Guanajuato, an area evangelized by the Franciscans; it is more political than devotional since it is not due to a founding miracle, an apparition nor is it near a river, an eye of water, or a sacred mountain. From the 18th century, a feast in honor of San Miguel was held in a community called La Labor. In 1869 the first bishop of Leon visited the area and noticed that there was disorder, so he gave instructions to move the image of the saint to the municipal seat, to have control of the celebration, but the people did not accept it and therefore a new celebration was started in the municipal seat.

The sanctuary acquired importance at the end of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century and nowadays it gathers people from Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas, Durango, Nuevo León, Jalisco, Mexico City, as well as other entities. It is also the main religious festival in northern Guanajuato, beginning on September 27 and ending on October 1. The municipality is still small in terms of the number of inhabitants, it has approximately 119 thousand, but about 20 thousand additional people arrive on those dates. In addition to the religious festivity, the local fair is held, organized by the municipal authorities who take advantage of the arrival of pilgrims to carry out civic, sports, and cultural activities.