Eight amazing women scientists whose merit was taken by men

All of these women made great discoveries, but they were left in the shadows. Their achievements were either attributed to their male colleagues or they were denied the Nobel Prize.

These women made great discoveries but were left in the shadows. Their achievements were either attributed to their male colleagues or they were denied the Nobel Prize. This is what is called the "Matilda effect."

Apart from Marie Curie or Hypatia of Alexandria, there are not many popular women in the history of science. However, there are many cases of women who have been flagrantly ignored, and have had to fight against sexism or work in miserable conditions so that in the end, after so much effort, their discoveries were attributed to their male colleagues and even to their husbands!

The number of female Nobel laureates since the awards were first presented in 1901 is less than twenty, and the reason for this is not only the fact that fewer women have access to scientific careers but also the highly questionable criteria of the Swedish Academy over the years.

The prejudice has a name, the "Matilda effect", the tendency to belittle scientific achievements if they have been carried out by women. Nettie Stevens, discoverer of the chromosomes that determine sex; Rosalind Franklin, whose contributions were essential for the discovery of the structure of DNA, or Lise Meitner, "mother" of nuclear fission, are some of those "Matildas" to whom justice still needs to be done.

Here we remember some of them, although there are more, on the occasion of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science. Fortunately, times have changed (or are changing), but the blacklist may be getting longer. In the last edition of the Nobel Prize, once again, no female name was mentioned in the announcements of the jury's decision... and no one can claim that this was due to a lack of female candidates. Forgetting is a bad thing.

Nettie Stevens

American geneticist Nettie Stevens (1861-1912) conducted exhaustive research on insects whose main conclusion would revolutionize the world of science: it is two types of chromosomes, X and Y, that determine the sex of a living being, something that was completely unknown at the beginning of the 20th century. Her work also provided evidence of how hereditary traits are obtained. But, bad luck, Stevens published her work at the same time as her prestigious colleague Edmund B. Wilson and it is easy to know who got the glory.

Wilson acknowledged in the journal "Science" that his conclusions coincided with those of his colleague, so he was aware of the study, but for a long time, it was he who appeared as the real discoverer. No one now doubts that Stevens is one of the great biologists and geneticists in history. Unfortunately, she died of breast cancer when she was only 50 years old.

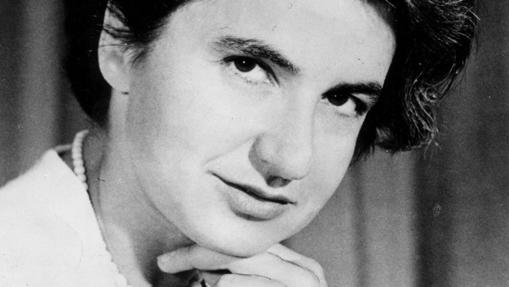

Rosalind Franklin, that "badly dressed feminist"

The wealthy father of Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958), a banker in London, was not very happy that his daughter wanted to study chemistry, and even withdrew her allowance, but the determination of the young woman made him change his decision and pay the expenses. Thus a brilliant mind was formed, whose contributions were essential for the discovery of the structure of DNA together with James Watson and Francis Crick. But her male colleagues were not exactly very gracious to her. To begin with, in the "Nature" article in which they published her findings, Franklin is mentioned in the last paragraph, in which they thank her for her unpublished experimental results and ideas as if she were a kind of "scholar".

Years later, in the book "The Double Helix", Watson referred to her saying that the best place for a feminist was someone else's laboratory. And added such unpresentable paragraphs as this: "She was determined not to emphasize her feminine attributes (...) She might have been very pretty if she had shown the slightest interest in dressing well. But she did not (...) All her dresses showed the imagination of nerdy English teenage girls".

For his part, Crick admitted that Franklin could not have coffee in the staff room at King's College because it was reserved for men, a circumstance he considered simply a "triviality". It was a long time before both scientists recognized the extraordinary scientific quality of their colleague and apologized. They were awarded the Nobel together with Maurice Wilkins when she had already died, and it is not awarded posthumously.

Lise Meitner, the suffering of the atomic woman

The story of the Austrian Lise Meitner (1878-1968) is one of scorn and hardship due to her double condition, that of being a woman and a Jew. "Mother" of nuclear fission (the splitting of a heavy atom into less heavy and more stable ones) and received in the USA as a celebrity after World War II, today she is hardly known. She did not share the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her laboratory partner Otto Hahn for reasons that are difficult to understand. And on top of that Hahn did not even mention her when he collected the prize in 1947 despite their 30-year collaboration. That was possibly the pinnacle of the many slights Meitner had to go through during her scientific career.

For example, at her first job in Berlin, at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in 1907, she was forced to work in a former carpenter's workshop set up in the basement, as the laboratory did not allow women. Unpaid, her work was financed by her father, so she lived in a room in a women's dormitory without a bathroom. It would not be the last free or underpaid collaboration she would be offered in her life. However, she loved her work to the point of putting her life in danger in Nazi Germany.

One more fact about Meitner's strong personality: she was the only scientist who did not want to collaborate in the Manhattan Project because she did not want to have anything to do with a bomb. At least Meitner did receive other important awards, such as the Max Planck Medal in 1949, and an element of the periodic table is named in her honor: meitnerium.

Isabella Karle, glory to her husband

American Isabella Helen Lugski (1921-2017), better known as Isabella Karle, her married name, developed a series of techniques to determine the three-dimensional structure of molecules by X-ray crystallography. But the 1985 Nobel Prize in Chemistry went to her husband, fellow chemist Jerome Karle, and his collaborator, Herbert A. Hauptman. She did not count for the committee of these awards, which has only awarded 3% of the prizes to women.

As her daughter explained to the media after Lugski's death from a brain tumor, this scientist was inspired by another great woman in her career: Marie Curie, a Nobel laureate, who, like her family, was born in what is now Poland. Of course, she had to overcome the discouragement of a teacher, who, when she was very young, told her that chemistry was not an appropriate field for young ladies.

Gerty Cori, together even at the Nobel Prize

For the members of the Swedish Academy in 1947, a married couple must have been something like an indivisible organic entity, so much so that when they awarded the Nobel Prize to Gerty and Carl Cori for their discovery of the process of catalytic conversion of glycogen. Shared with the Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay, the prize money was not divided among the three winners but was split in two: one part for the couple and one for Houssay.

At least, Gerty Cori (1896-1957) became the first woman in the world to win the Nobel Prize in Medicine. It was not easy for her; she had to deal with sexism throughout her professional life. Some universities would give her husband a job but refused to hire her or offered her ridiculous salaries.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell, at the boss's command

Signs of interplanetary intelligent life? No, they are pulsars. They were discovered by Northern Irishwoman Jocelyn Bell Burnell (1943) while doing her doctoral thesis at Cambridge University (England). After analyzing a huge amount of data obtained by a radio telescope that she helped to build, she found the signals of these stellar corpses that rotate around themselves at great speed.

However, the Nobel Prize for this discovery was awarded to her thesis supervisor, Anthony Hewish, and Martin Ryle, also an astronomer at Cambridge. Bell Burnell herself explained to National Geographic in 2013 that "the image people had at the time of how science was done was of an old man who had a bunch of underlings under him, who were expected to do what he said."

Chien-Shiung Wu, the "Chinese Marie Curie"

Chien-Shiung Wu (1912-1977), also known as the "Chinese Marie Curie" or "Madame Wu" is one of the great experimental physicists of the 20th century, which is quite an achievement considering she was born in a small town near Shanghai at a time when girls did not go to school and were still blindfolded. Thanks to her family's support, Wu not only studied but reached the highest academic levels.

Recruited to Columbia University in the 1940s as part of the Manhattan Project, she researched radiation detection and uranium enrichment. She disproved the physical law of conservation of parity with her colleagues Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang, a study that won her the Nobel Prize in 1957. But once again the Academy awarded the men and forgot the women. The decision was considered by many to be scandalous.

Agnes Pockels, the housewife who did physics in dishwater

When Agnes Pockels (1862-1935) finished her studies, German universities did not admit women, and when they did, her parents would not let her enroll. So this young woman, born in Venice, devoted herself to taking care of her family and had no other job than that of a housewife. However, she managed to study physics with her brother's books, the knowledge that she applied to what was closest at hand: dishwater.

In this way, Pockels developed a device to measure surface tension in substances such as oils, fats, soaps, and detergents. Her studies were published in "Nature", but the world forgot all about her and it was Irving Langmuir who won the Nobel Prize in 1932 for perfecting Pockels' original idea.

Source: Science, Technology, and Innovation Agency of the Province of Jujuy